When my son turned 12, he asked for his first smartphone. My wife and I did what many parents do in such a situation: We reflexively said no. Let’s round back in a year or two. Maybe three.

However, kiddo was persistent in that way only a middle schooler could be, so we spent the next few weeks reading articles, researching parental controls, and asking others for sage advice. There were late-night conversations, maybe a verbal scuffle or two. Eventually, we decided he could have a hand-me-down phone. Our son was happy, and we were proud to have reached this family watershed with such care, thoughtfulness, and poise.

If only the poise were to last. Turns out, getting your child a smartphone — or any digital technology — isn’t the end of a difficult decision. It’s the prologue to the many difficult decisions to come.

On the one hand, teenagers need to engage with their peers during these years of social development, and digital technologies have become an inseparable part of building and maintaining those relationships. Teens chat with their friends over text, play games online, and build entire communities of like-minded people on social media. Not letting your child connect through these platforms is potentially shutting them off from the shared cultural experiences that strengthen social bonds.

On the other, parents must care for their children’s health — physical and emotional — and many worry that digital technologies are harmful on both fronts. Not only do these technologies compete for our limited attention and make our lives more stationary, but they are also gateways to vast amounts of misinformation, disturbing content, abusive drive-by encounters, and harmful social comparisons. The teenage mind is not equipped to handle all that cultural sewage. (I mean, it’s not like the adult mind handles it all that well either.)

What are parents to do?

A potential answer comes from the work of Andrew Przybylski and Netta Weinstein, psychologists at the Oxford Internet Institute. In 2017, they published the results of a large-scale, pre-registered study in which they reviewed data on the tech habits of 120,000 adolescents. They found that heavy, daily technology use was correlated with poorer mental well-being in teens.

More surprising was the correlation for teens who spent little to no time with digital technology. Like their tech-heavy peers, they also reported worse mental health scores than those who spent a few hours surfing the internet, texting their friends, or playing video games. Since then, other researchers have replicated Przybylski and Weinstein’s findings.

These results led Przybylski and Weinstein to propose the “digital Goldilocks hypothesis.” It argues that a certain amount of digital technology use isn’t intrinsically harmful to teens and may even be advantageous. As the name suggests, that amount is not too much, not too little.

While the study didn’t reveal a one-size-fits-all prescription, other research has suggested ways to help families craft their Goldilocks zone around digital technology.

First, ease your worry

The internet can be a scary place. We’ve all taken that blind turn online and come face-to-face with something we’d rather forget — to say nothing of making our children deal with it. Unless you’re some digital dictator who can build a personal “Great Firewall,” this reality means letting your child go online entails risks. The ideas, images, and opinions they encounter will affect their mental health.

“It would be really weird if it didn’t,” Pete Etchells, a psychologist at Bath Spa University, told Freethink in an interview. “That’s also different to saying that social media or smartphones or whatever are the predominant drivers of poor mental health [among teens].”

Etchells points out that digital technologies do have the potential to amplify teens’ mental health problems in some cases — the news media and your social media feed are right about that. However, such coverage is often breathless and one-sided. In other cases, those same technologies may offer a mental balm. The reason for these divergent outcomes, as with most things related to mental health, is a complex interplay of personalities, environment, social support systems, life experiences, and good old-fashioned luck.

The challenge for parents is working with their teens to determine what they require to thrive and how to set healthy boundaries around technology to promote those needs. But parents can’t meet that challenge if they approach the online world like a dark wood in a fairy tale, one full of unspeakable horrors where children dare not tread.

A better approach, Etchells says, is to consider the “ecosystem of factors.” Ask yourself: What factors do you think your child will be most vulnerable to? How do you help them avoid those or offer support should they encounter them? What factors will enliven your child emotionally, socially, and intellectually? How do you create the conditions to help them find and enjoy those?

Think “screen habits,” not “screen time”

If the Goldilocks hypothesis is true, then you’d think a simple solution would be to set a daily timer. Let’s say an hour on school days and — what the heck — three on the weekends. Problem solved, right? If only.

This “screen time” approach may have worked for your mom and dad when it came to getting you outside and away from your PlayStation. However, the days when screens are used primarily for passive or non-social activities are long gone. Today’s teens use screens to do homework, read books, socialize with friends, video chat with out-of-state grandparents, and many other mentally and socially stimulating pursuits. Sometimes, they even watch TV on them.

“How much we use [screens] isn’t as helpful as considering both the content we consume and the context in which they play a part in our lives,” Etchells writes in his book Unlocked: The Real Science of Screen Time (and how to spend it better). Instead of thinking in terms of screen time, he recommends approaching conversations with your teen with a mind toward “screen habits.”

Consider all the ways your teen uses their digital technologies. Where are they using their screens and when? Is the screen use intentionally geared toward enriching pursuits, such as learning, connecting with friends, or engaging in a hobby? Or are they scrolling through YouTube recommendations and social media feeds in mindless, disconnected ways?

“It’s in answering those questions that we’ll be able to better understand where we’re getting benefits, and where there are things that we would like to change,” he writes.

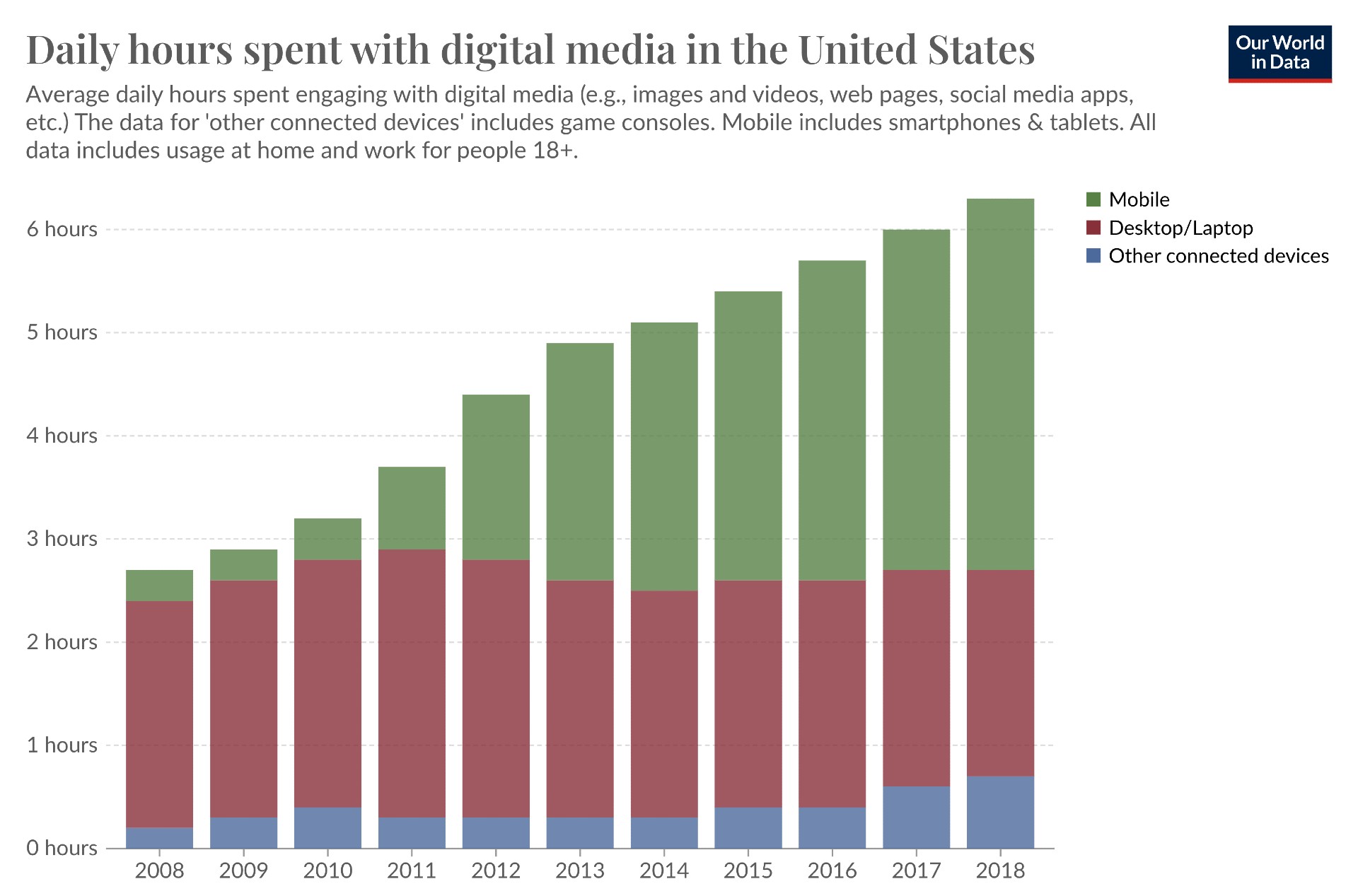

That’s not to say that time on screens doesn’t matter. In their research, Przybylski and Weinstein noted that well-being scores began to drop off at roughly two hours of screen time on weekdays. But on weekends, that inflection point was much higher at about four hours a day. They also found that some digital activities were better suited to weekdays, such as using computers versus playing video games.

“It’s not like banning kids from having phones until they’re 16 will magically [teach] them how to use them when they get to age.”

Pete Etchells

However, their research suggested that the “nature” of the engagement was as important as the amount of time. For instance, they speculate that computers appear better suited for weekdays because they require less disruptive “task-switching” than video games. And while weekend screen time averaged higher, it could still lead to problems if it became dysregulated or displaced “other beneficial weekend social activities.”

“Reshaping our thinking in this way [can] empower us to make small changes, here and there, that can build up into meaningful improvements in our relationship with screens,” Etchells writes.

Work with, not against, your teen

Once you’ve talked with your teen about their screen habits, you can begin forming a plan together. It’s here that parents often get hung up on the details: When can teens use these technologies, for how long, on what apps, etc.? Those are necessary details to consider, but the critical part is the word together.

During our interview, Etchells pointed to research looking at teens’ willingness to follow or break technology rules based on parenting style. The researchers asked teens about authoritarian parenting — the “it’s my way or the highway” style — and guilt-trippy parents — “Why don’t you listen? Don’t you love us?”

They also considered what they called “autonomy-supportive parenting.” This approach discusses rules with their teens, listens to their concerns, and acknowledges their agency. It’s not an entirely permissive approach since parents still set and enforce boundaries, but they do so with communication and connection.

It found that teens in authoritarian and guilt-trippy conditions reported a willingness to rebel against the rules. Meanwhile, teens in the autonomy-supportive parenting condition… also reported a willingness to break the rules.

“Because they’re kids, and that’s what kids do,” Etchells says. “They push boundaries.”

Even so, there was an important difference: Those in the autonomy-supportive condition reported being less likely to hide their tech use and more willing to talk about it.

“It’s not guaranteed that because [your child] comes across something harmful [online] that it will cause trauma,” Etchells says. “But they will absolutely need to talk to people about it. You need to create a situation in your families where regardless of what the rule was, if that sort of thing happens, they can come and talk to you about it.”

That research, Etchells notes, is still preliminary, but by approaching teen tech use from the perspective of screen habits and autonomy-supportive parenting, you can have more productive conversations around those all-important details, such as:

- What sites are acceptable and how to safely search information online.

- How to set notifications and rules on app downloads.

- How to prevent digital technology from interfering with things like sleep, physical activity, and real-time connections with friends and family.

- Where to set boundaries while leaving room for your teen to maintain their relationships and pursue hobbies, off and online.

“It’s not like banning kids from having phones until they’re 16 will magically [teach] them how to use them when they get that age,” Etchells points out. “What you need to do is build those digital literacy skills leading up to that point.”

Interrogate your screen habits

“Do as I say, not as I do” has never been an effective parenting strategy. If your technology habits interfere with your sleep, physical activity, and relationships, your teen will pick up on the discrepancy. You may think you have better reasons than they do, but from your teenager’s perspective, a work email following up on an overdue TPS report is no more important than a text from Clarissa bookended by fire emojis.

“I think one of the most important things that we can do is think about how we model the behaviors that we want to instill in our kids,” Etchells says. “Because they look up to you. They’ll mimic stuff that you’re doing.”

Rather than hide your struggles, be honest about them and use these conversations as opportunities to build healthier habits for yourself, too. These reflections work just as well for you as your teen. As a bonus, by working with your family to make small adjustments to your own screen habits, you build stronger connections with your teen and normalize the struggles and challenges they may be facing.

No such thing as “just right”

So, have I taken my own advice with my family? Yes … mostly.

We’ve told my son no to social media for now as we would prefer his online interactions to be with people he knows in real life. We do, however, let him engage with friends regularly online through games, text chats, and Facetime. We’ve also talked about how to engage people online politely, how to keep Google searches safe, and how to steer clear of the internet’s darker corners.

Over time, he’s gained a little more freedom, but at 13 now, I still monitor his online activity closely. I may also, on occasion, end a frustratingly long conversation with an authoritative “because I said so” — he is, still, persistent in that way only a middle schooler can be. But I do try to round back when heads have cooled.

From these experiences, I can tell you that the Goldilocks hypothesis can help, but won’t solve, the challenge of raising a teenager in the era of digital technology.

Recall that Przybylski and Weinstein’s study looked at the correlation between mental health and technology use. It couldn’t determine a causal relationship between the two, so it’s possible that certain screen habits lead to poorer mental health or that poor mental health leads one to certain screen habits. It’s also possible that a third, unconsidered factor moves the needle for both.

But even if we could prove a causal relationship, it wouldn’t change the fact that every family situation is unique and every teen’s needs different. You would still need to consider how your teen’s offline life informs the struggles and successes they’ll encounter online. You would still need to balance the many trade-offs. Even if you found a “just right” solution, it would quickly be disrupted as your teen ages, their needs change, and the technology evolves.

And that’s okay because good parenting isn’t about creating perfect conditions. It’s showing your child how to build healthy habits, maintain fulfilling relationships, and stay resilient in the face of an imperfect online — and offline — world.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].