Among the 20 million people worldwide living with schizophrenia, auditory hallucinations are one of the most common symptoms — yet we still lack a reliable understanding or treatment of them.

“(Existing drugs) don’t work for everybody, and they have a lot of terrible side effects which prevent people from using them,” Eleanor Simpson, a researcher at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, told NPR.

Now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis (WUSTL) and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory have designed a computer game that can trigger auditory hallucinations in both lab mice and humans — a discovery that could open the door for much-needed new treatments for schizophrenia.

Treating Auditory Hallucinations

Mice might not look much like humans, but their genetics, biology, and behaviors are very similar to ours.

That’s made the tiny rodents invaluable to medical research — by creating “mouse models” of human diseases, such as cancer, scientists can study the illnesses’ progression and test treatments in living organisms without risking any human lives.

There still isn’t a great mouse model for schizophrenia, though, and until there is, researchers will have a difficult time developing better treatments for the disease or its symptoms.

“Animal models have driven advances in every other field of biomedicine,” senior author Adam Kepecs said in a press release. “We’re not going to make progress in treating psychiatric illnesses until we have a good way to model them in animals.”

Game Time

To see if they could make a connection between auditory hallucinations in people and lab mice, Kepecs, first author Katharina Schmack, and their collaborators created a hallucination-triggering computer game that both species could “play.”

In the game, mice and humans must indicate when they hear a particular sound — the mice do this by poking their noses through a specific hole, while people click a button.

The mice and the humans thought they heard the sound even when it wasn’t played.

Players must also show their confidence that they heard the sound. The mice do that by waiting for a reward: the longer they wait, the higher their confidence that they really heard the sound. People, meanwhile, indicate their confidence by adjusting a slider on a scale.

To make the sound harder to hear, the game obscures it with background noise.

By playing the sound frequently at first, both the mice and the humans could be primed to expect to hear it. They would then report high confidence in hearing the sound even when it wasn’t played — they were experiencing auditory hallucinations.

Driven by Dopamine

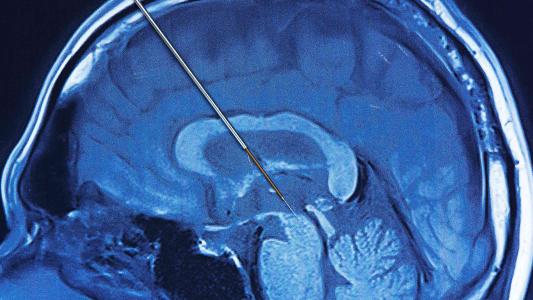

After successfully triggering auditory hallucinations in both the mice and the humans, the researchers began studying the animals’ brains during the game. That’s when they discovered a link between the hallucinations and higher dopamine levels in a mouse’s brain.

“There seems to be a neural circuit in the brain that balances prior beliefs and evidence, and the higher the baseline level of dopamine, the more you rely on your prior beliefs,” Kepecs said.

“We think that hallucinations occur when this neural circuit gets unbalanced, and antipsychotics rebalance it.”

We need a good way to model psychiatric illnesses in animals to make progress in treatments.

Adam Kepecs

This isn’t the first study to link dopamine to hallucinations, but it is the first to demonstrate a way to study auditory hallucinations across species.

Because the human brain and mental illness are so complex, it’s not certain that these hallucinations are the same phenomenon that is experienced in schizophrenia.

But if they are sufficiently similar, researchers could now use the discovery to test drugs that might prevent auditory hallucinations in mice — and hopefully, find ones that can translate to treatments for schizophrenia in humans.

Editor’s Note, 4/13/21, 9:20 ET: This article was updated to add the names of additional study contributors.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].