Does where you live have any bearing on the kind of personality you have? Science says yes, and these maps show how.

But which science is that, exactly? It sounds like something cooked up after hours in the back alley between the geography and psychology departments. When this rogue discipline becomes respectable enough to get its own lab, it will need its own name.

The nascent field of geopsychology

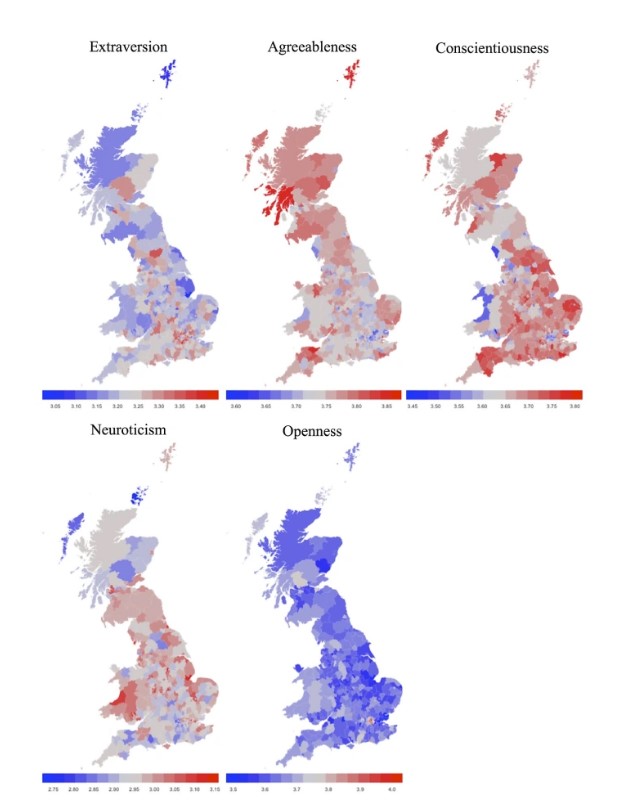

“Psychogeography” is already taken — basically, it’s a fancy term for “walking while moody.” “Geopsychology,” however, is still available. And it sounds just about right to describe the systematic study of regional differences in the distribution of personality traits. Especially since those differences do indeed seem to be “robust.”

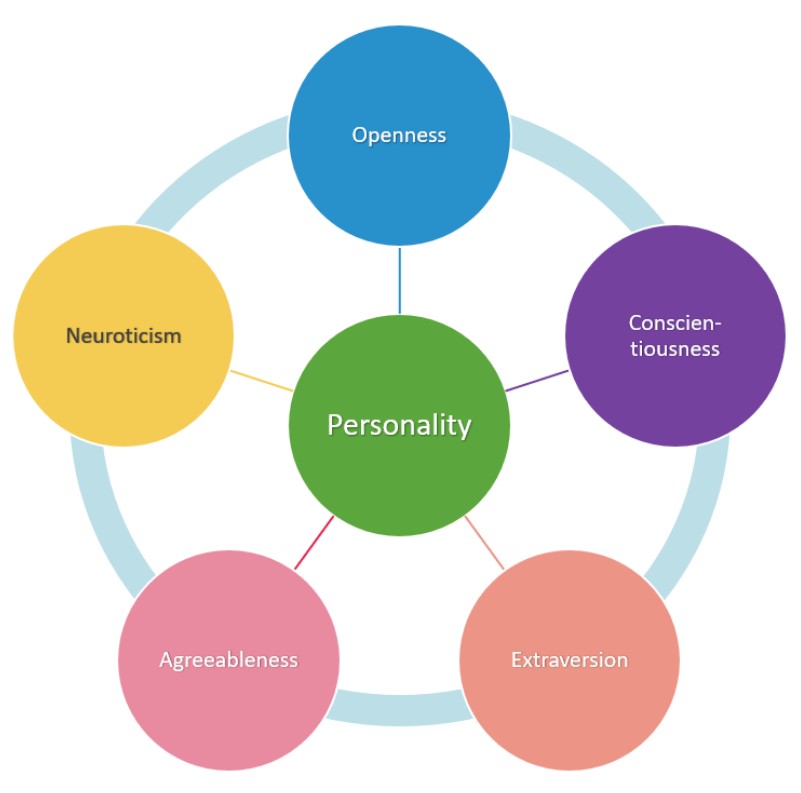

The traits examined on the maps are the so-called Big Five, a grouping of five broad personality dimensions that started gaining currency in academic psychology from the 1980s and often referred to by their acronym, CANOE:

- Conscientiousness

- Agreeableness

- Neuroticism (a.k.a., Emotional Stability)

- Openness

- Extraversion

Each trait is a spectrum. More conscientious means more efficient and organized; less conscientious means more extravagant and careless. Agreeableness ranges from friendly and compassionate on one end of the scale to critical and rational on the other. Neuroticism ranges from sensitivity and nervousness to resilience and confidence. Openness, from curiosity to caution. And extraversion, from outgoing to solitary.

The usual caveat applies: none of these traits should be taken in isolation, neither for cause nor effect. Studies — of twins, for instance — show these characteristics are about equally influenced by nature and nurture: that is, half of your behavioral makeup is due to genetics, the other half to environment. Also interesting is the finding that while four out of five traits remain stable into old age, “agreeableness” does show variation as subjects get older.

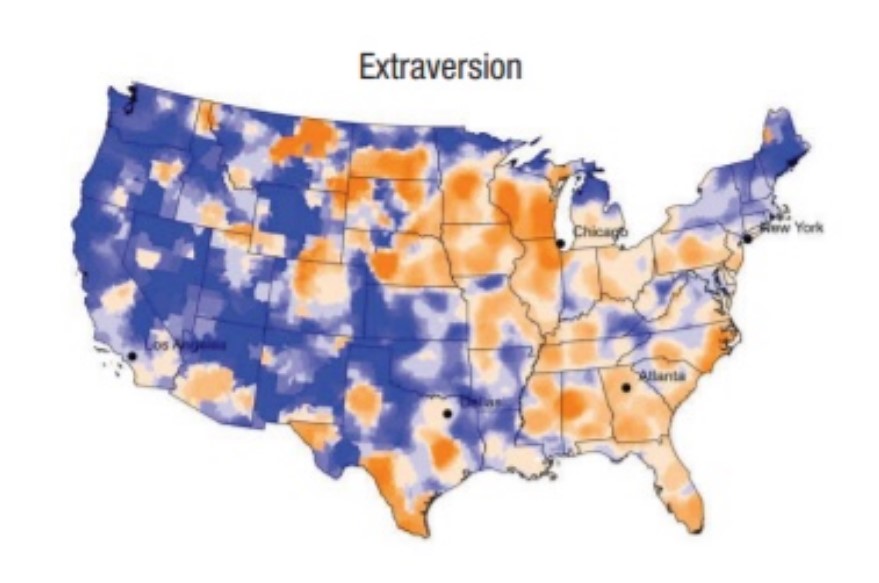

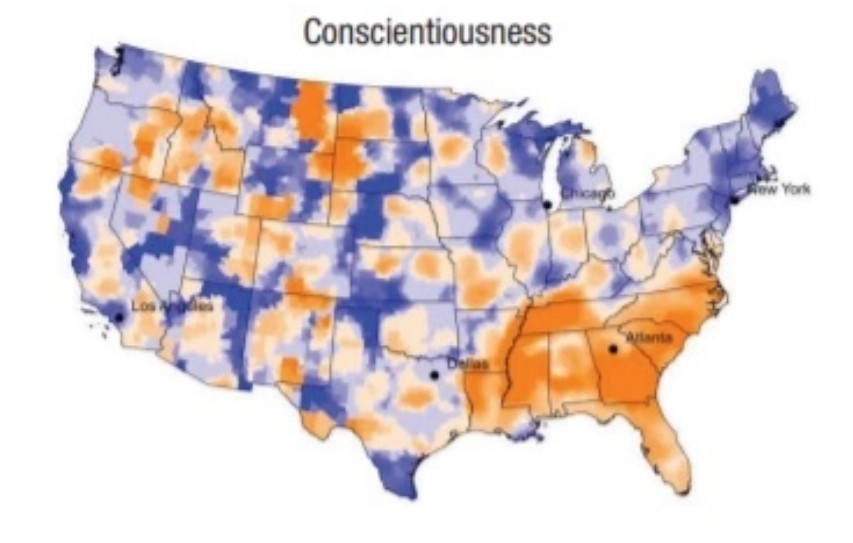

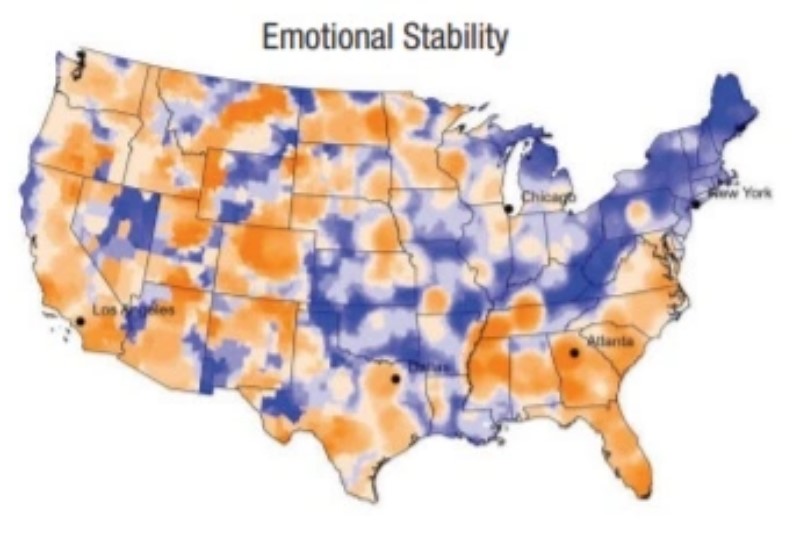

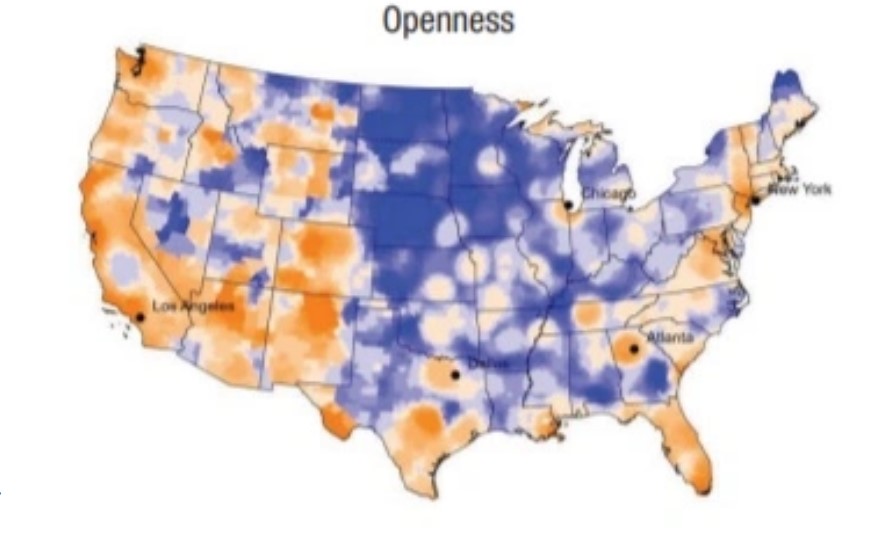

Amongst all those variables, geographic location seems to have a significant effect on the prevalence of these traits — hence, geopsychology. On these maps, orange means higher than average, blue means lower. Darker means greater distance from the average.

Extraverts: Where’s the party?

Extraverts are “the life of the party,” while introverts, on the other side of the scale, require less stimulation from people or events.

Extraversion appears to be highest across central Northern states (including Wisconsin, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska), in the Rust Belt (Ohio, Pennsylvania) and in the South (Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida). There are pockets of extraversion across Texas and elsewhere, but large parts of the Northwestern, Western, and Pacific states score well below average.

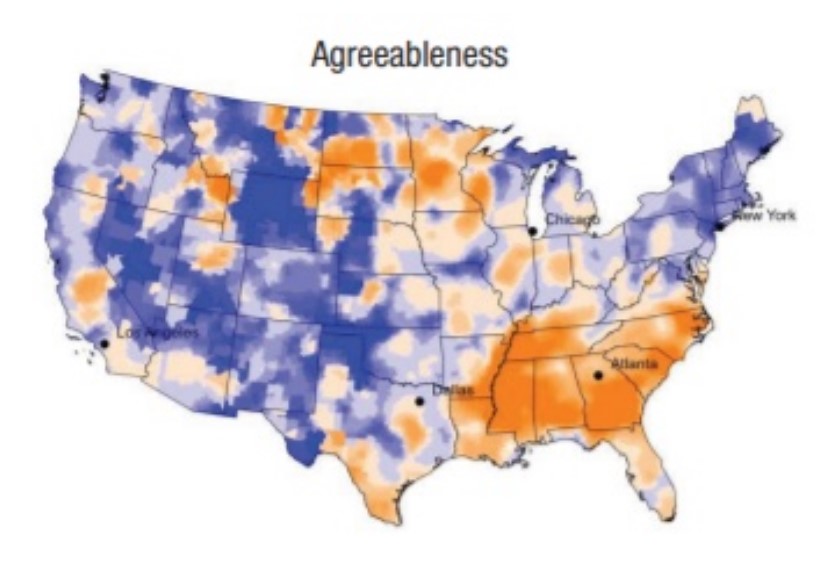

Agreeableness: social harmony vs. self-interest

People who are “agreeable” aim for social harmony, by being kind and considerate, and are prepared to compromise on their goals. “Disagreeable” people have a less optimistic and less cooperative view of others, giving precedence to self-interest. They are more competitive and argumentative.

The presence of agreeableness is most pronounced in the South (Louisiana to North Carolina, with hotter and colder zones in Arkansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Florida). A second important cluster was found in and around Minnesota and the Dakotas. The dark blue of disagreeableness hangs heaviest over Western states, from Montana to New Mexico, and from Nevada to the western halves of Kansas and Oklahoma. There is an additional grumpiness epicenter in New England.

Duty and discipline down South

High levels of conscientiousness display as a strong sense of duty, a high degree of discipline, and an intense desire to outperform expectations. Low conscientiousness can manifest as being spontaneous and flexible, but perhaps also less orderly and reliable.

The highest levels of conscientiousness were measured again in the South, but with plenty of clusters elsewhere in the country — with a particularly dark orange spot in the Dakota-Montana-Wyoming borderlands. On the other end of the scale, the largest patch of unbroken blue is in the Northeast, but with darker veins running through the center and west of the country.

A dark band of emotional instability

To be emotionally unstable (a.k.a., neurotic) means one is prone to experience anger, depression, anxiety, and other negative emotions. This may be linked to low stress tolerance. On the other end of the scale, emotionally stable individuals are free from persistent negative emotions.

The score for emotional stability was highest throughout the western half and southern part of the country. Apart from an island of stability in central Pennsylvania, a dark band of emotional instability stretches from Maine to northern Alabama, spilling over into the Midwest and West, all the way to Kansas and Oklahoma.

The open-closed divide

A high degree of openness signals a willingness to try new things, as well as a higher awareness of one’s own feelings and creative talents. Low openness signals seeking fulfillment through perseverance rather than euphoria and being pragmatic — or perhaps even dogmatic.

There is an almost linear divide in levels of openness. The area west of the eastern state borders of Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico is dominated by high levels of openness, with some exceptions. The area to the east of that line is mostly blue — again, with notable exceptions, for example Chicago, southern Texas, Florida, northern Georgia, and the area around New York.

Some of these results confirm long-standing stereotypes. However, the results also offer a level of detail that confounds many others. For example, California’s relatively high degree of “openness” chimes with the state’s progressive image. But the significant degree of variation for most of the characteristics illustrates that the state is far from culturally monolithic. The same for supposedly conservative Texas, where the results for large metropolitan areas like Dallas, Houston, and Austin deviate significantly from those in other parts of the state.

These traits help explain many aspects of human behavior. For example, studies suggest that people who are more conscientious and agreeable are more likely to achieve academic success than those who score higher on the neurotic scale. Also, by clearly exposing these statistically relevant variations in personality type by region, geopsychology may prove an important tool for marketeers, political and otherwise.

Perhaps the still relatively young science of geopsychology will get its own shiny new building sooner rather than later.

For more on geopsychology, see Tobias Ebert et al., Perspect. Psychol. Sci., 2021. Also see a working paper on regional differences in personality published in 2019 by the geography department at the University of Marburg in Germany. (Download a PDF of the article here.)

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.