This article is an installment of The Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

Brave, an open-sourced web browser, has become the first browser to fully integrate a direct peer-to-peer networking protocol. This has the potential to fundamentally change how the internet works.

The technology that Brave uses is called the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS). It’s a decentralized, peer-to-peer file-sharing system that connects all computers using the same system of files — thereby eliminating the need for a central server.

IPFS makes file sharing and streaming speeds faster, and, more importantly, it makes websites less vulnerable to failure and censorship.

“Today, Web users across the world are unable to access restricted content, including, for example, parts of Wikipedia in Thailand, over 100,000 blocked websites in Turkey, and critical access to COVID-19 information in China,” said Molly Mackinlay, an IPFS project leader at Protocol Labs, which developed the system in 2015.

“Now anyone with an internet connection can access this critical information through IPFS on the Brave browser.”

A Single Point of Failure

In order to talk to each other, we need to speak the same language. The same is true of computers. Today, the internet is dominated by a language called HyperText Transfer Protocol (the acronym HTTP in your URLs).

This system relies on a client-server relationship. Whenever you go to a website, your computer must request the data from the server that hosts that website, even if that server is physically very far away.

The server will send each person the website’s data individually. That means that if there are 10 million people trying to access a website, the server will have to respond at least 10 million times.

IPFS would make the internet faster and less vulnerable to failure and censorship.

Hackers sometimes take down websites by flooding them with a huge number of fake requests, making it impossible for genuine users to get through. But in general, this process has worked reliably because the data we were sharing was relatively small — texts, emails, small images.

But it’s pretty inefficient for transferring big data, like HD video. And today, video streaming is over 60% of all internet traffic.

Another issue with centralized servers: whoever controls the servers controls the data. So, anyone with access to the server — whether a government entity or a hostile hacker — can access and potentially censor or alter the information. Or, as in the case of the 38 million websites hosted by GeoCities, websites can just disappear if the web hosting service gets yanked.

How IPFS Works

Instead of relying on a client-server relationship, IPFS allows users to leverage their geographic proximity to each other to more efficiently — and quickly — retrieve the data they need.

Software engineer Karen Kwatra puts the difference bluntly: with HTTP, you are asking what is at a certain location; with IPFS you are asking where a certain file is.

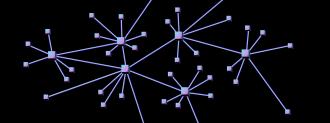

With IPFS, the data (photos, articles, videos, etc.) is distributed across a network of computers. Each individual computer — called a “node” — can store the data, as well as request data from other nodes. And all files are version controlled, meaning all changes are tracked and verified.

In short, IPFS acts like a combination of Git and BitTorrent. Like Git, it stores and tracks changes to files over time. And like BitTorrent, it shares the files via a distributed network.

“We use content-addressing so content can be decoupled from origin servers, and instead, can be stored permanently. This means content can be stored and served very close to the user, perhaps even from a computer in the same room,” Juan Benet, creator of IPFS, told TechCrunch in 2015.

But destroying truly malevolent websites, like child pornography, would become much more difficult.

He added that it “allows us to verify the data too, because other hosts may be untrusted. And once the user’s device has the content, it can be cached indefinitely.”

With a distributed network, information online could theoretically live forever, essentially creating a “permanent web.”

While this sounds great when thinking about it in terms of halting government censorship, it could also make destroying truly malevolent websites, like child pornography, much more difficult. (Thankfully, Benet told Wired that users can choose which data they want to store, so it’s unlikely that you’d unknowingly play host to illegal content).

Here’s a more mundane scenario: what if you just really want to delete that old, embarrassing blog post from 2006? According to Wired, Benet said in 2016 that his team is working on a “recall” function, which would let publishers “recall” certain pages that are being shared and stored. It’s not clear how this function would work in real life, but if it does, then the question becomes: what’s to stop governments from using the recall function, too?

IPFS is still pretty new and there are a lot of things to work out before wide-scale adoption — so HTTP isn’t likely to be replaced anytime soon. Currently, Brave is using IPFS to complement HTTP in order to boost browsing speed and reduce censorship.

The Marketplace

One issue to work out is that users are able to access IPFS content via a “public gateway” — which means, there’s no real incentive for anyone to actually store the data on their computer by becoming a local node. And even if they do become a node, there’s no reason for them to maintain the data long-term — they can always clear cached data to save space on their device. So, theoretically, if no nodes exist for hosting the data, files could disappear over time, which definitely doesn’t work towards the idea of a permanent internet.

As Hackernoon points out, this isn’t really a problem right now, but if IPFS is adopted on a larger scale, we’ll need to backup huge amounts of data — and this will likely require economic incentive.

Enter: Filecoin.

IPFS users could use Filecoin, a separate protocol designed to give economic incentives for people to store data. Filecoin essentially acts as a storage marketplace, allowing users to rent out their hard drives.

According to Hackernoon, Filecoin is being developed on Ethereum, a cryptocurrency platform, so “‘in theory, this economic model should develop a highly competitive free market with potentially lower costs than large-scale providers.”

Permanent Web

Benet isn’t the only one concerned with losing digital information — the original inventors of the internet are, too. Vinton Cerf, whose nickname is the grandfather of the internet, told Wired that he’s concerned about a digital dark age where important information simply becomes inaccessible.

Many people may not understand the importance of a digital archive — after all, if you’re concerned enough about a particular site or specific photos or videos, you can just back up the data or convert it to a newer digital format. But Cerf says that line of thinking is short-sighted — people don’t always know what will be important in the future.

With a permanent web, we wouldn’t have to decide.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].