Why are traditional climate solutions falling short in the American South?

Why are traditional climate solutions falling short in the American South?

In Brunswick, Georgia, a predominantly Black community lives in the shadow of industrial facilities, where decades of conventional environmental advocacy have failed to create meaningful change.

This isn’t just an anomaly. It’s a pattern repeated across the American South, where traditional climate solutions often overlook the complexities of environmental impact, public health, and community prosperity. From industrial pollution to basic infrastructure, the environmental burden on Black communities in the South often manifests in health disparities:

- The area from Baton Rouge to New Orleans has been dubbed Cancer Alley due to its abundance of petrochemical plants and refineries. The census tract within this area (St. John Parish) has the highest cancer risk from industrial air pollution in the United States – more than seven times the national average

- While Alabama’s Black Belt makes up less than 0.2% of the U.S. population, it accounts for over 12% of Americans lacking basic water and plumbing systems

- Nationally, Black Americans are more likely to die from stroke than white Americans – but that disparity is between 6% and 21% higher in Southern states

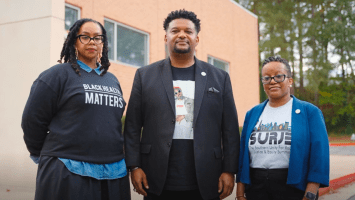

However, these communities have gained a fighting partner in their corner. In Atlanta’s Partnership for Southern Equity (PSE), a nonprofit organization that advances racial equity and shared prosperity in the American South, an innovative new approach to environmental justice is emerging.

Nathanial Smith, founder and Chief Equity Officer of PSE, puts it bluntly when asked why he thinks Black communities are disproportionately impacted. “For people in particular communities of color, racism is the social determinant of health,” says Smith. “Racism has facilitated environments that continue to harm historically disinvested communities of color.”

Smith’s organization aims to change the South’s attitude towards environmental issues affecting marginalized communities and is already producing measurable results by connecting environmental justice directly to community health and generational wealth.

This is how PSE is taking action.

The Battle For Brunswick

Brunswick has 14 sites on Georgia’s Hazardous Sites Inventory—including four Superfund sites (areas designated by the government to contain chemicals toxic to humans), more than any other Georgia city. The danger these sites pose was illustrated in November 2023, when a chemical fire at the Pinova plant sent hazardous plumes of smoke across nearby neighborhoods, forcing residents to seek shelter.

“A lot of times poor communities have to choose between their health and their pocketbooks,” says Smith. “There’s this perception that it’s going to be a job creator for the community. But unfortunately, those jobs can create years of illnesses or the companies may not hire within the community like they said they would.”

It’s long been suggested by residents that these sites were detrimentally affecting their health, but it wasn’t until PSE worked with Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health that the data showed what was truly going on.

Researchers from the university analyzed blood samples from 100 long-term Brunswick residents. The results, published in early 2024, showed elevated levels of multiple cancer-causing toxic substances. Risk for higher exposure was elevated for individuals who are Black, older, work at industrial facilities like LCP Chemicals or Hercules, or live with someone who did. Most telling was the presence of Aroclor 1268, a toxic man-made chemical linked specifically to Brunswick’s industrial sites.

The findings confirm long-held fears for community members like local doula Wendy Brown. “My son was playing soccer and they practiced next to a Superfund site. How did we know? Because one day a fence came up,” she recalls. “Is my son contaminated? I don’t know. But they’re going to tell me now.”

Brown, who works with expectant mothers in the local area, points to Georgia’s troubling maternal health statistics – the state ranks 46th nationally in healthcare and has an infant mortality rate of 6.25 deaths per 1,000 live births, which is higher than the national average of 5.6. In Brunswick, these health outcomes are even worse than the state’s already poor averages.

All of this evidence has sparked a movement. Researchers are now seeking to expand the study to 500 participants and examine potential health impacts. For PSE, the data provides communities with hard evidence to advocate for change—transforming generations of speculation into actionable proof of environmental injustice.

All of this evidence has sparked a movement. Researchers are now seeking to expand the study to 500 participants and examine potential health impacts.

But PSE’s approach goes beyond just gathering data—they’re helping communities use this information to advocate for real, comprehensive change. Working with local partners like Coastal Community Health and the Environmental Justice Advisory Board, they’re creating a model where environmental cleanup, healthcare access, and community empowerment work together. Now healthcare providers are being trained to recognize pollution-related health issues, while community members are learning to document and report environmental violations.

Restoring Black Excellence In Sweet Auburn

In the heart of Atlanta lies a stark reminder of how poorly planned infrastructure can harm community prosperity. Sweet Auburn Avenue, once dubbed “the richest Negro street in America,” stood as a testament to Black entrepreneurship and resilience during the Jim Crow era. Here, Black-owned insurance companies, banks, and entertainment venues created a thriving ecosystem of commerce and culture.

Then came the highway.

In the mid-1960s, the Interstate 75/85 “downtown connector” tore through Sweet Auburn. The construction displaced an estimated 30,000 residents and dealt a deadly blow to the district’s vitality. With no direct highway access to Auburn Avenue, traffic was deliberately diverted around the community. Bustling storefronts were replaced by empty lots and boarded-up buildings. This physical divide created by the highway resulted in decades of disinvestment and disregard, marking the end of Sweet Auburn’s golden age.

“Sweet Auburn was an extremely vibrant and important community to the Black nation,” Smith explains. “But in the eyes of white leadership, they still considered it blighted, which they used as an excuse to build a highway through Auburn Avenue.”

Today, a coalition of organizations is working to heal this rift. PSE has joined forces with Perkins & Will and Nelson\Nygaard in the Reconnecting Sweet Auburn Project, an initiative funded by Invest Atlanta, Sweet Auburn Works, and the Atlanta Downtown Improvement District (ADID).

The team has set specific goals: documenting the long-term negative effects of the highway construction using hard data about physical infrastructure, environmental conditions, and demographic changes. They’re also studying successful examples nationwide of how other divided communities have rebuilt and reconnected. In late 2024, the project took a major step forward, applying for an $800,000 Reconnecting Communities Pilot Grant to advance their design recommendations.

The project also aims to deliver immediate, community-led design interventions to improve quality of life while developing longer-term strategies to reimagine Sweet Auburn’s relationship with the highway that divided it. This includes the chance to reconfigure existing infrastructure, like streets, ramps, and bridges, to make the neighborhood more livable and attract new investment.

The challenge now is ensuring Sweet Auburn’s revival benefits its existing community rather than pushing them out. As neighborhoods improve, rising property values often displace the very residents who weathered decades of disinvestment. But Smith is confident in his community-first approach. “We believe that a resilience agenda cannot be fully realized without a healing and repair agenda,” he says. “It’s not just about beautifying places—it’s about healing people and positioning people to be successful.”

A Data-Driven Path Forward

PSE’s approach has already shown concrete results. In Atlanta, where 90% of major job centers are located north of Interstate 20 while many underserved communities live south of it, the organization achieved its first major policy win by expanding public transportation. Working with faith communities and young people, PSE launched “The Power of the Penny” campaign, convincing residents to support a one-cent sales tax for transit expansion. The initiative secured over 70% voter approval, creating a $13 million fund to extend MARTA (Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority). This wasn’t just about transportation – with more cars sitting in traffic due to a lack of accessible transit options, Atlanta’s carbon footprint was expanding and residents, especially children and seniors, were suffering from increased air pollution. PSE’s success demonstrated how addressing transportation equity could simultaneously tackle environmental justice and public health.

PSE’s success offers a clear blueprint for addressing environmental challenges across the South. Their model, supported by Skoll Foundation funding, demonstrates how combining health data, community leadership, and environmental advocacy creates measurable change. This approach has already helped over a hundred organizations secure $60 million through former President Biden’s Justice 40 Executive Order, showing how local successes can scale to regional impact.

“Equity is love in action,” explains Smith. “We can’t facilitate an environment where all people have a chance to reach their full potential if we’re not courageous enough to love everybody.” This philosophy drives PSE’s commitment to ensuring communities lead their transformation, from fighting utility rate increases that burden low-income residents to developing the South’s first equity mapping tool.

For PSE, the future is about continuing to expand its impact across the South while staying true to its core principle that those closest to problems are closest to solutions. Their experience shows that successful environmental justice work requires more than just data and policy change – it demands creating spaces where local community members can unite to build a more equitable future.

This story was reported as part of a partnership with the Skoll Foundation. Through their support of social entrepreneurs tackling society’s most urgent challenges, they’re helping organizations like PSE create lasting, systemic change for those who need it most. Visit Skoll.org to explore more stories of impact.

In the American South, systemic disinvestment has left Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities vulnerable to environmental hazards. In Brunswick, Georgia, Black neighborhoods face toxic Superfund sites and recurring disasters like a 2023 chemical plant explosion. The Partnership for Southern Equity (PSE) is rethinking what’s possible, mobilizing communities for environmental justice. Rooted in Dr. King’s legacy, PSE is driving policy change and proving that when equity leads, transformation follows.

Indigenous Peoples are guardians of the world’s forests, playing a vital role in preserving these crucial ecosystems. But as their land rights and livelihoods come under increasing threat, these defenders are standing strong, fighting for the land and working with organizations like Global Witness to expose the institutions responsible for its destruction.

By shedding light on the financial institutions backing companies like JBS, Global Witness is exposing the impact of environmental damage and aiding defenders in their fight to protect and preserve our planet’s forests.

Indigenous communities like the Maasai in Tanzania are being displaced as governments and corporations exploit their valuable resources. They are being relocated in the name of conservation, while their land is being used for profit. Despite facing eviction and rights violations, these communities continue to protect their natural homelands. Indigenous people make up 6% of the global population but protect 60-80% of remaining biodiversity.

Now, thanks to organizations like Indigenous Peoples’ Rights International (IPRI), they are able to amplify their voices and fight for their rights on a global scale.