Take a look around the animal kingdom, and you’ll see that tails are super common and super useful — they propel fish through water, give cows a way to keep flies at bay, and help monkeys swing through forests.

So why did humans and other great apes evolve to be tailless? And, specifically, how did we do it?

That question has puzzled scientists for as long as we’ve known that evolution was a thing — and researchers at NYU just got us a major step closer to answering it.

25 million years ago: Past research has found that more than 100 genes play a role in tail development in vertebrates, and lead study author Bo Xia had a hunch that a mutation in one of them set human and ape ancestors on the path to taillessness, some 25 million years ago.

“It takes TWO to make an impact!”

Bo Xia

In search of that mutation, he compared the genomes of humans and five other species of apes to those of 15 species of monkeys with tails. This led to the discovery that tailless primates have an extra bit of DNA in one gene linked to tail development (called TBXT), which is missing from the tail-having monkeys.

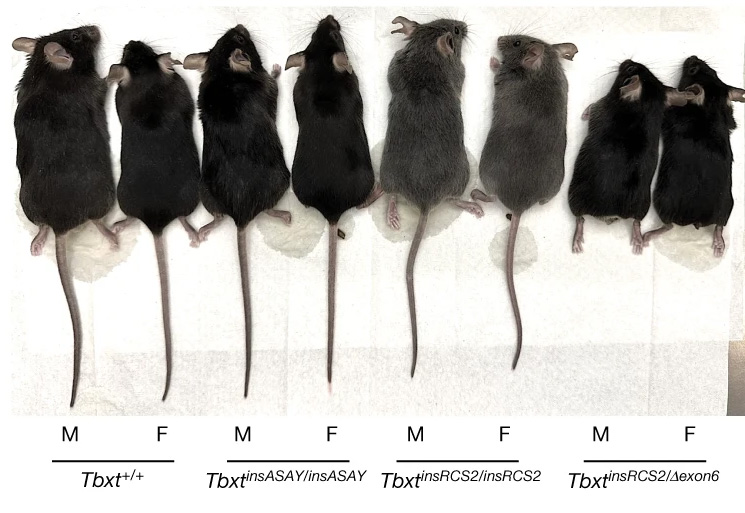

That didn’t prove the extra DNA causes tail loss, though, so the researchers did an experiment: using CRISPR, they inserted the mutation into the TBXT genes of mice. Surprisingly, though, these mice had normal tails. So what happened?

Take(s) two: It turns out, the extra DNA discovered in the TBXT genes is an example of an “Alu element.” These sequences can be found throughout primate genomes, and they’ve long been considered non-functional, or “junk,” DNA.

When the researchers took a closer look at their primate genomes, they discovered a second Alu element that seemed to be paired up with the first one, and when they used CRISPR to insert both bits of “junk DNA” into mice, the rodents were born tailless or with just short tails.

“[I]t takes TWO to make an impact!” tweeted Xia. “The unique alignment of a pair of Alu elements is crucial; without it, neither element would have significance.”

Another mystery solved? The NYU study doesn’t explain why taillessness was beneficial, but an understanding of how we lost our tails could help unravel the mystery. Whatever the reason, the pros must have been significant, because the second experiment did reveal a major con to tail loss: mice with the extra DNA in their TBXT genes were also more likely to have neural tube defects.

“Future experiments will test the theory that in an ancient evolutionary trade-off, the loss of a tail in humans contributed to the neural tube birth defects, like those involved in spinal bifida, that are seen today in one in a thousand human neonates,” said senior co-author Itai Yanai.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].