In the Marvel comic world, there is a character called Rogue. She herself has very few superpowers, but her power comes from her ability to absorb other heroes’ powers and use them herself. If someone can fly, has super strength, or has super healing, she can make these powers her own. And, as with a lot of science fiction, this may not be as outlandish as we might think.

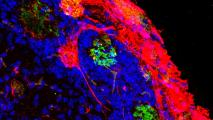

Deep in the oceans, there lies a tiny, slimy superhero — the nudibranch (pronounced noo-dee-brank). The nudibranch is often only about 2 cm long and is known for incredible colors. Since they derive their coloring almost exclusively from what they eat, the nudibranch often stands out as a garish, polychromatic explosion. There’s even an entire website comparing the nudibranch to David Bowie costumes. But this is just the beginning of what these remarkably little sea slugs can do.

Body snatchers

The ocean is scary. One of the reasons is the existence of a prickly group of animals called the “cnidaria” (the “c” is silent). The group includes jellyfish, anemones, hydroids, and other similar species. One of the defining characteristics of cnidaria is that they use barbed, stinging weapons on their body to both catch prey and deter would-be predators. These venom-filled harpoons are usually very effective, and many of the neighborhood animals are sensible enough to give them a wide berth.

But not nudibranchs. Certain species of nudibranchs, called aeolids, have evolved not only to eat and digest various cnidaria but to steal their weapons as well. When an aeolid eats one of these venomous cnidaria, the first thing they will do is make sure that the lethal stinging cells won’t go off. Some of these stingers will be excreted along with other waste, but some are stored away in their outer “cerata,” which are finger-like structures on their backs. If these aeolids are then threatened by other species, they will use the stolen venom as a defense mechanism.

It’s telling that nudibranchs have very few predators and are mostly at risk only from other nudibranchs.

Solar powered sea slugs

But this is not the only power the nudibranch can harness to its own ends. One genus of nudibranchs, called Phyllodesmium (also an aeolid, as it happens) have learned how to be “solar powered.”

These sea slugs feed on soft corals and are able to strip them of algae without damaging that algae’s capacity to photosynthesize. Just as they do with venomous spears, the nudibranch will shuffle these algae into their cerata, where they will go on turning light into sugar, supplying the nudibranch with a little booster of sun-powered energy. It’s even the case that the algae continue to reproduce, possibly even faster than in their natural habitat, suggesting that they prefer their enslaved life.

The largest and most efficient of these nudibranchs can load up their cerata with algae and resemble nothing so much as slimy solar panels, with up to a quarter of their energy requirements provided by their photosynthesizing algae.

Body regeneration: getting a-head of others

While the ability to absorb and repurpose other animals’ talents is pretty useful, that’s not all the nudibranch has going for them. If things really get tough, they can jettison their entirebody. Researchers have found that the nudibranch can survive self-decapitation, where it leaves behind it’s beating heart and major organs. This means that they will sometimes abandon 85 percent of their own body mass.

It is unclear why exactly the nudibranch would need to do this. As mentioned above, they have very few predators, and the entire process is so onerous and time-consuming to be of any use if caught in the jaws of some would-be attacker. A good guess might be that it is a form of defense against parasites or a virus or if one of its organs begins to fail.

But, whatever the reason, it’s a pretty neat trick. Within a day, they have sealed off their wounds. Within a week, the organs are regrowing in new bodies. And in just over two weeks, they are entirely good to go. Imagine how useful it would be if humans could replace a cancerous lung, a weakened heart, or a cirrhotic liver. And, in fact, some researchers are using the nudibranch, as well as other similar regenerators, to discern clues about how we can help combat human organ damage.

So, not only are the nudibranchs really cool to look at and not only do they have superhero-like powers, but they might just hold the key to one of the greatest medical advances of all time.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.