As we enter the age of artificial intelligence and the internet, what can a printing press from 1450 teach us about how these technologies will develop and shape our societies?

As journalist, professor and media theorist Jeff Jarvis sets out in his book, The Gutenberg Parenthesis, the dominance of the printed word may be coming to an end, but are we ready for the next stage of our tech evolution?

Robin Pomeroy, host of the podcast Radio Davos, caught up with the author at the World Economic Forum’s recent AI Governance Summit in San Francisco. Here are some edited highlights from their discussion around the transformative role of technology and how our lack of certainty as to where the internet and AI will ultimately take us.

What is the Gutenberg Parenthesis?

Johann Gutenberg was an inventor and master craftsman who printed the Bible using his moveable-type printing press in 1450-1454. His version of automating the book-printing process may not have been the first, but it paved the way for the rapid dissemination of knowledge.

The concept of The Gutenberg Parenthesis suggests that the era of print – which began in the 15th century and extended to the 20th century when radio and television muscled in – was a unique period for human communication. Most information during that time came from books, newspapers and other print media.

As we move away from this era, some argue that we are returning to the pre-Gutenberg times, and we are about to see a new phase in which the flow of information will become more fluid, even easier, to access.

The power of new technology

“I’m not saying that history repeats itself or even that it’s a carbon copy or sings in harmony. Nonetheless, we went through a tremendous transition in society when print arrived,” Jarvis explains.

“Huge societal change occurred, and I think that we have lessons from that about technological change, about societal change, about adaptation, about the dangers that exist. And so I wanted to look back at that and really learn about the culture and history of print so that we could try to judge also who we were in it as we now make decisions about what to hold on to, or not, as we leave it.”

The dawn of a new communication era

The early days of the printing press paved the way for new formats and mediums for the printed word, and by around 1600, it finally became commonplace, says Jarvis, with “the invention of the essay by Montaigne, the modern novel by Cervantes, the newspaper, and a market for printed plays by Shakespeare”.

But the print press did not stay the same over the 500-year period, Jarvis points out – technology allowed for the emergence of the steam-powered print press in the 1800s, and various other advancements, which allowed for faster publishing and vastly increased output.

Then in 1991, the world wide web opened up to the general public, and so began a new way to pass on information. And now we have AI to contend with. This new technology is just beginning, and we do not know its full potential, Jarvis says.

“[But] one of the lessons from the Gutenberg years is, the technology fades, the technology gets boring. And when the technology gets boring, it gets important, because then we accept it and we don’t see it as technology. And so I think that it is important to look at technology, the internet, as a human network.”

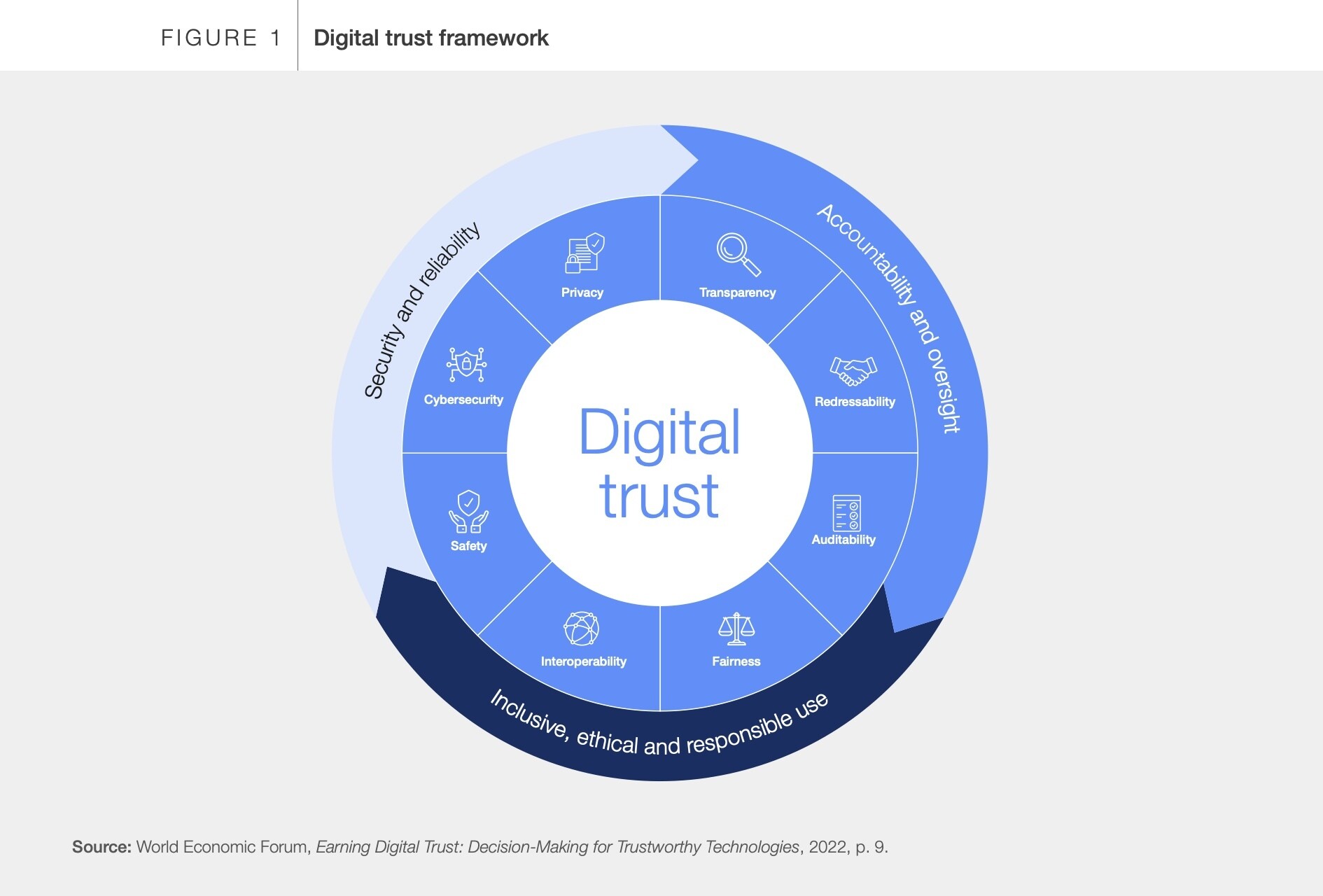

Trust and new technologies

When it comes to AI, society is a long way off finding it boring. Yet the reaction to new technologies does not appear to have changed much over the past 500 years, Jarvis explains. The printing press was met with almost as much suspicion and concern as generative AI is today – perhaps with good reason.

“It’s important to say that when print came along, it was not trusted at all because the provenance was not clear. Anybody could print a pamphlet, just like anybody can make a tweet or a Facebook post or a blog. And so what was trusted more was the social relations you have with people.”

For Jarvis, the issue has parallels with today’s ongoing debate about media trust. But the arrival of the internet has given those without a mainstream voice, a chance to be heard.

“In America, we had our most famous news anchor Walter Cronkite. And he would end every broadcast by saying, ‘And that’s the way it is’. But for many, many Americans, it wasn’t the way it was. They were not represented there. They were not served there. Now they have a voice.

“I look at Black Lives Matter potentially as a definition of a reformation that was able to start because of this new technology that allows communities who were previously not heard to be heard.”

The era of AI

At the San Francisco AI Governance Summit, the discussion centred around how to control or regulate AI to deal with unintended consequences. As the EU and other regions grapple with how best to regulate AI, Jarvis wonders if regulation is indeed the answer.

“Can we control this?” he asks. ”Well, why do you want to? To what end?”

Instead of focusing on how to control AI, Jarvis concludes that we need to bring people together to judge both the internet and AI through the prism of being human.

“AI is a machine that can now finally understand us when we speak to it. It’s now taking on a human nature. And so what we need is ethics and anthropology and sociology and psychology and history and the humanities brought into this discussion,” he says.

“We have to acknowledge the human frailties and failures that we bring to these technologies. That’s what we’re guarding against. It’s not that the technology is dangerous. It’s that we can be dangerous with it.”

This article is republished from the World Economic Forum under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.