Perplexity, Google, and the battle for AI search supremacy

Can AI-powered “answer engines” replace the 10 blue links model?

This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Saturday morning by subscribing here.

It’s 2026, and the way you search the web has radically changed. Now, instead of telling you where to find answers, Google and other search engines all use AI to answer your questions directly — no link clicking required. Where things go from here is anyone’s guess.

Answer engines

The web contains billions of pages, and we rely heavily on search engines to help us find the information we need within that trove of data — we ask a question, or just throw keywords out, and the search engine gives us a list of links to relevant pages.

Now, large language models (LLMs) — AIs trained on huge sections of the internet to produce text in response to user prompts — are enabling search engines to generate answers in response to questions, saving us from having to click on links and hunt for the information ourselves.

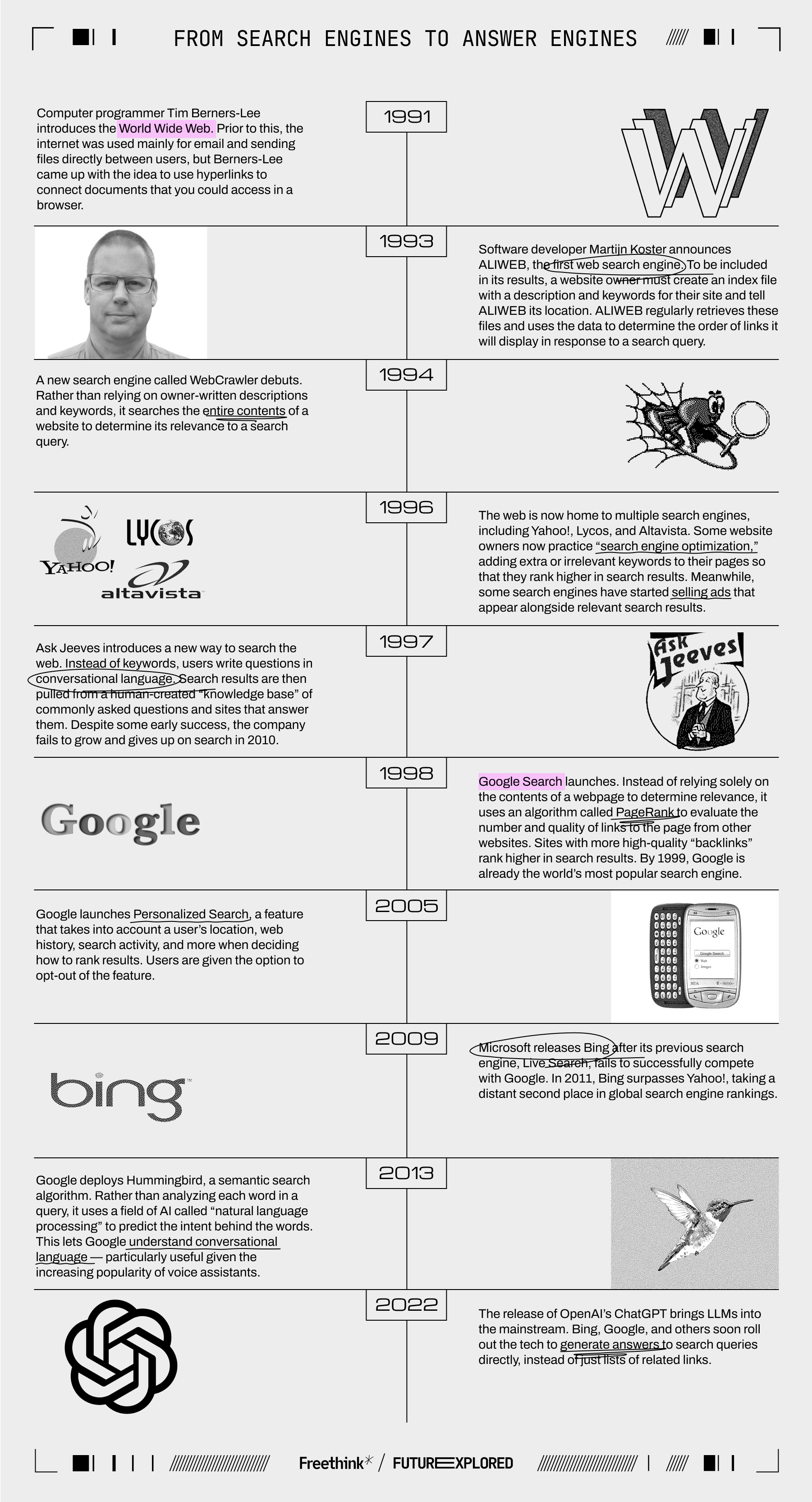

To find out what this means for the future of the internet, let’s look back at the history of web searches, the issues LLM-powered “answer engines” will need to overcome to replace the standard 10 blue links, and what will come next.

Where we’ve been

Where we’re going (maybe)

LLMs could radically change how we find information on the web. Instead of search engines acting like middle men that tell us where to go to find answers, the tech could turn them into answer engines that just tell us whatever we want to know — no extra clicks required.

Google is already exploring this possibility.

In 2023, it started testing the Search Generative Experience, an experiment in integrating an LLM into its Search platform. In May 2024, it rolled out AI Overviews to all US users — now when you ask Google a question, you often receive a response written in conversational language above the links to relevant sites.

Microsoft, the closest thing Google has to a competitor in the search space, moved even faster. In February 2023, it launched a new version of Bing that displays a response from Copilot — an AI chatbot built on GPT-4, a powerful version of the LLM behind ChatGPT — in addition to standard search results.

Startups such as Perplexity and Andi, meanwhile, are gaining traction with search engines designed from the ground up to provide LLM-generated answers.

“Answer engines” powered by LLMs could be the future of search.

So far, LLMs haven’t radically changed how we search the web. Bing gained just about 1% of the search market share since the launch of Copilot, but Google still has more than 90% of it, and none of these AI startups has yet made a dent.

It’s still possible that “answer engines” powered by LLMs will be the future of search, though. It’s even possible that Google won’t be the company to dominate this new era — but many hurdles currently stand between us, that future, and whatever comes after it.

Large language liars

LLMs are great at replicating human language because they’ve seen a lot of it — the LLM behind ChatGPT, for example, was trained on 300 billion words pulled from the internet, books, and other sources.

From looking at all this data, LLMs learn to notice patterns in language. They can then generate human-like text by learning connections between words and predicting what is most likely to come next in a sentence based on the words that came before it.

“Examples on how AI overviews are turning Google search into garbage are all over my timeline.”

Gergely Orosz

The problem is that LLMs will sometimes “hallucinate,” confidently presenting false information as true — within days of Google rolling out AI Overview, users were sharing stories about how the AI told them that you can cook spaghetti in gasoline and that a dog had played in the NHL.

“Google Search is…the one property Google needs to keep relevant/trustworthy/useful, and yet examples on how AI overviews are turning Google search into garbage are all over my timeline,” tweeted Gergely Orosz, author of tech newsletter The Pragmatic Engineer.

While Google, Microsoft, and others are working to minimize hallucinations, some AI experts think eliminating them is simply impossible, due to the fundamental mechanics of how LLMs work.

Dmitry Shevelenko, Perplexity’s Chief Business Officer, told Freethink the company includes link citations alongside all of its AI’s answers, which “builds a layer of trust,” but if people have to click links to ensure the information they’re getting from an answer engine is accurate, they might just stick with traditional search.

Slop in, slop out

LLMs are doing more than shaking up search — they’re changing the entire internet, and not necessarily for the better.

Now that the AIs are widely accessible, scammers are using them to generate keyword-packed, low-quality content, aka “slop,” for their websites. They’re also using the tools to rewrite existing articles from reputable publishers, such as WIRED, TechCrunch, and Reuters.

That AI-generated content is now ranking highly in Google’s search results, jeopardizing our ability to find useful, original information through the ol’ fashioned method of searching.

“It’s the worst quality results on Google I’ve seen in my 14-year career,” Lily Ray, senior director of SEO at digital marketing agency Amsive Digital, told Fortune in January 2024. “Right now, it feels like the scammers are winning.”

AI-generated “slop” is jeopardizing our ability to find reliable information on the web.

Google is trying to combat the slop problem with algorithm updates, but if the content is already showing up in traditional search results, it could start appearing in the answers generated by LLM-powered search engines, too, simply because the AIs don’t know any better.

Some of AI Overview’s weird responses, such as advising people to use glue in their pizza recipes and eat rocks for nutrition, may have seemed like random hallucinations initially, but the LLM was working as intended, repeating information it found online — it just didn’t know the authors were joking.

If a significant portion of the internet is low-quality, unreliable content, AI-powered search engines could have even more trouble delivering helpful answers.

Plagiarism problems

While scammers are using LLMs to deliberately rip off credible news sites, AI-powered search engines may be doing something similar, albeit seemingly unintentionally.

Instead of searching the web for information and then compiling what they find into useful original answers, Google’s AI Overview, Microsoft’s Copilot, and Perplexity have all generated responses to queries that repeat content from other websites word for word.

“Perplexity’s success hinges on the existence of a healthy information ecosystem.”

Dmitry Shevelenko

The New York Times has said it tried to reach an “amicable resolution” with Microsoft about the use of its content, but those negotiations didn’t pan out, so it’s now suing the tech giant.

Perplexity, meanwhile, has responded to the plagiarism issue by making citations more prominent, and Shevelenko told Freethink that the company is also developing a revenue-sharing program that would earn publishers money when their site is cited in a search response.

“We’ve always understood that Perplexity’s success hinges on the existence of a healthy information ecosystem,” said Shevelenko. “If there are no longer trusted news outlets reporting on the facts, then we would lose real-time information to serve users.”

AIs are responding to search queries with answers that repeat content from other websites word for word.

Google’s plan seems to be trying to convince publishers that its AI Overviews are just “conceptually matching” their existing content and that they’re actually benefiting from the whole situation.

“We see that links included in AI Overviews get more clicks than if the page had appeared as a traditional web listing for that query,” a Google spokesperson told WIRED (they did not provide any data showing this to the publication).

Whether or not that’s true, many news outlets are already struggling, and if they aren’t benefiting from having their work appear in answer engines, they could lose the incentive to create high-quality content altogether — bringing us back to the problem of an internet overrun with slop.

The business model

Making money isn’t just a concern for content creators competing with LLMs. It’s still not clear how AI-powered search engines themselves are going to be profitable.

The majority of Google’s revenue comes from ads listed alongside search results, and in May 2024, it announced plans to start placing ads above and below AI Overviews and, in some cases, even within them in a special “Sponsored” section.

It’s too soon to say how this could affect Google’s advertising income, but if users are getting the answers they need from AI Overviews, they might not only click fewer outside links (and fewer ads on those websites) but also fewer sponsored ads on search results. If advertisers aren’t getting clicks, they could stop paying for ads to appear in Google’s search results.

“There are still more questions than answers as to how Google’s search ad revenues will fare with the introduction of AI Overviews,” Evelyn Mitchell-Wolf, a senior analyst at eMarketer, told Yahoo! Finance.

“There are still more questions than answers as to how Google’s search ad revenues will fare.”

Evelyn Mitchell-Wolf

That’s the revenue side, but there’s also a cost issue.

LLMs require enormous computing power, which means they have significant energy costs. In February 2023, John Hennessy, chairman of the board at Alphabet, Google’s parent company, told Reuters that it costs 10 times more to use an LLM to generate an answer to a search query than to deliver the standard lists of links.

Alphabet’s CEO Sundar Pichai has said he is “confident” that Google will be able to manage these costs and the “monetization transition,” but AI-powered search is definitely squeezing the business model.

Perplexity is currently funded by investors, but it believes the path to future profitability includes multiple revenue streams — users can already pay $20 per month for access to Perplexity’s most powerful AI models, and it plans to integrate ads into results in the future. Microsoft, meanwhile, is trying to develop a smaller, cheaper LLM to handle simpler queries.

Ultimately, LLM-powered search engines will need to be profitable to become the future of search, and right now, it’s not clear how companies are going to manage that.

The bottom line

If Google can overcome the above issues, it’s in excellent position to continue its reign as the king of search, but even if someone else does search better than Google, they’re going to have a seriously tough time dethroning the company.

Just weeks after the release of ChatGPT, Neeva — a startup cofounded by Sridhar Ramaswamy, ex-head of Google’s ad division — announced that it was launching an LLM-powered search engine. By February 2023, NeevaAI was available worldwide.

Three months later, though, the company shut down, and according to Ramaswamy and his co-founder Vivek Raghunathan, the problem wasn’t their product. It was that people didn’t want to leave the search engine they were already using — most likely Google.

“[T]hroughout this journey, we’ve discovered that it is one thing to build a search engine, and an entirely different thing to convince regular users of the need to switch to a better choice,” wrote Ramaswamy and Raghunathan in a May 2023 blog post.

“From the unnecessary friction required to change default search settings, to the challenges in helping people understand the difference between a search engine and a browser, acquiring users has been really hard,” they continued.

Ultimately, platforms that provide answers to our queries could be the future of search — or they could be something we briefly experimented with before returning to the list of links we’re used to. As with seemingly everything related to LLMs and generative AI, it’s simply too soon to confidently predict.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].