In 1999, Apple unveiled the Power Mac G4, a machine that became pivotal in the evolution of personal computing and a landmark in tech regulation. Unlike its predecessor, the aesthetically pioneering iMac, the Power Mac G4 broke new ground through sheer power. It achieved an astonishing computational capability of 1 gigaflop — a threshold that, under U.S. law at the time, put the device in the same category as exporting munitions.

This arms control classification stemmed from the 1979 Export Administration Act, a Cold War law designed to prevent supercomputers from reaching communist states. The rationale was straightforward yet reflective of its time: in 1979, a machine capable of 1 gigaflop was a marvel of engineering, a tool so powerful and potentially disruptive that it warranted stringent control.

Just 20 years later, this computational prowess had become accessible to the general public. Yet, the law hadn’t caught up with the rapid pace of technological advancement. The regulation of the Power Mac G4 under this outdated law is a striking example of the disconnect between the pace of legislation compared with technological innovation.

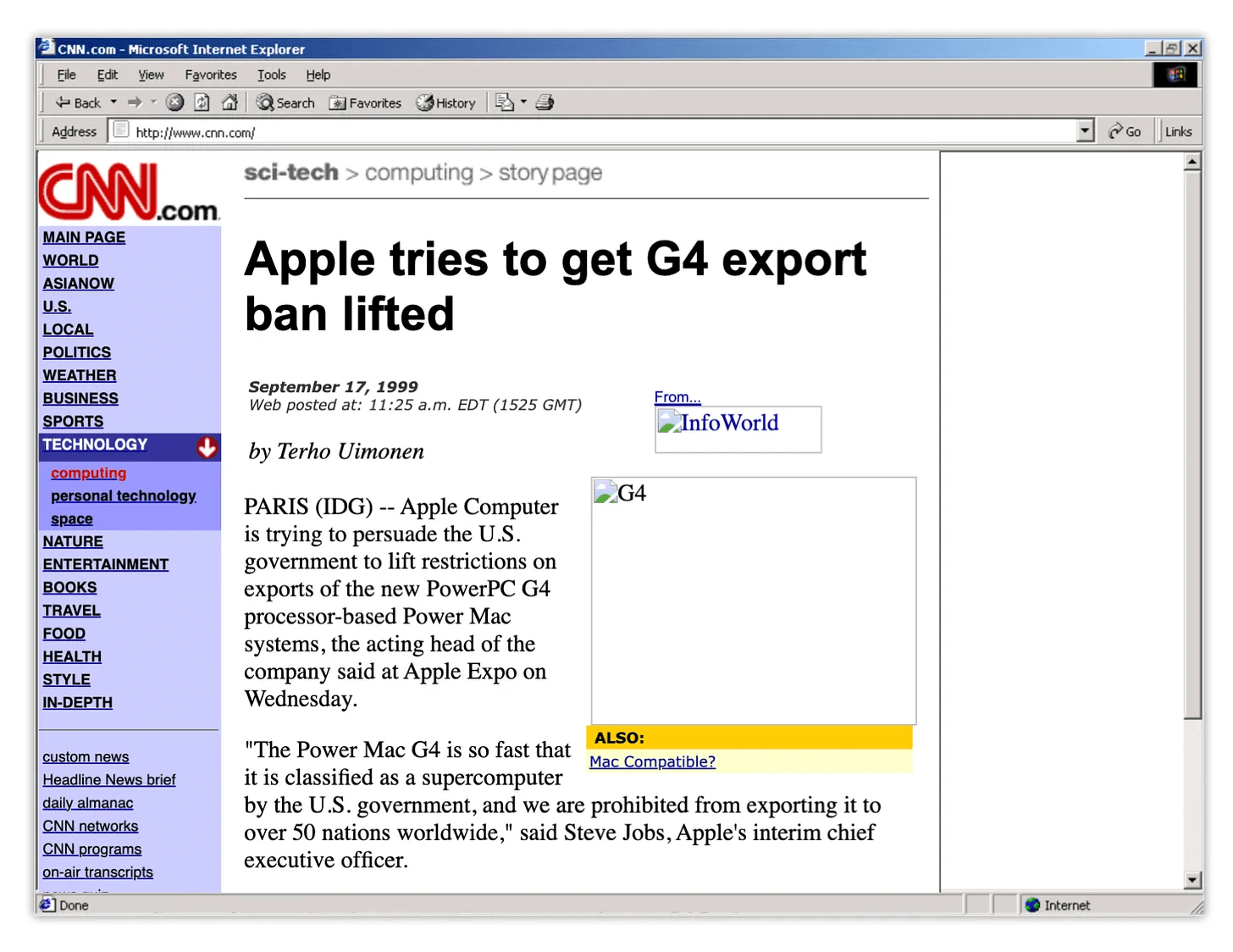

Apple, in its characteristic style, turned this regulatory hurdle into a marketing triumph. Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple, announced triumphantly at the G4’s unveiling: “The Power Mac G4 is so fast that it is classified as a supercomputer by the U.S. government, and we are prohibited from exporting it to over 50 nations worldwide.”

The company’s marketing department branded the G4 as a “Personal Supercomputer,” ingeniously leveraging its munitions classification. A television advertisement of the era depicted tanks encircling the computer, with a narration highlighting the U.S. government’s classification of the device. The ad concluded with the tongue-in-cheek reassurance: “As for Pentium PCs, well, they’re harmless.”

The Clinton administration eventually raised the gigaflop threshold for export controls in January 2000. This allowed Apple a brief period wherein it could exploit this classification for marketing purposes, even though the law was already on its way to being updated.

Today, this episode remains relevant, particularly as we grapple with the regulatory challenges posed by artificial intelligence. Power once deemed exclusive to government supercomputers is now surpassed manifold by consumer products. Apple’s M3 Mac boasts 4000 gigaflops and is freely exported worldwide.

There may be an echo of this historical episode in President Biden’s 2023 AI executive order, which introduced new fixed thresholds for AI regulation, possibly signaling a new era of computational regulation. The order sets reporting requirements for AI systems whose training required computer power exceeding “1e26 floating point operations or 1e23 integer operations.”

This journey from the Power Mac G4 to today’s AI regulation discourse illuminates a fundamental dynamic of technological progress: the continual recalibration between innovation and regulation. The Power Mac G4, once a “weapon” by legal standards, is now a quaint relic of a time when a gigaflop was a frontier. As we navigate the AI era, this historical perspective offers a crucial lesson: regulations must evolve in tandem with technology, lest they become obsolete relics of a bygone era.

The question is, will we look back in 50 years and chuckle at how we once perceived today’s impressive computing power levels as threatening? Or, in a more somber reflection, will we rue missed opportunities to harness and regulate these technologies appropriately? The story of the Power Mac G4 is more than a tale of a product; it’s a narrative about our relationship with the ever-advancing frontier of technology.

A version of this article first appeared on the Pessimists Archive Substack. Reprinted with permission.