Top flight animal sperm is big business — premium samples can run for tens of thousands of dollars. And animals bred from the finest of forefathers could improve livestock yields while helping to cut down on their ecological impact.

But artificial insemination poses challenges, too: there’s the cost, for one, and the reticence of some animals to, ahem, acquiesce to so passionless a liaison (goats in particular don’t like it, according to New Atlas).

The remote regions of the world, which would most benefit from having some strapping progeny ambling about, also have the hardest time acquiring select sperm.

But a team of researchers, led by Washington State University reproductive biologist Jon Oatley, have used CRISPR gene editing to come up with a possible solution: “surrogate sires,” four-legged sperm-factories who are themselves infertile but can produce a prized specimen’s sperm in their testes.

Basically, a bull can now go from toro blah-vo to toro bravo.

“With this technology, we can get better dissemination of desirable traits and improve the efficiency of food production. This can have a major impact on addressing food insecurity around the world,” Oatley told WSU News.

“If we can tackle this genetically, then that means less water, less feed and fewer antibiotics we have to put into the animals.”

The gene editing technique — published in PNAS — works thusly: using CRISPR-Cas9, the team knocks out the NANOS2 gene. NANOS2 controls male fertility; without it, the cattle, goats, mice, and pigs are born infertile.

But when sperm-producing stem cells from highly prized donors are inserted into the barren testes, the formerly infertile animals begin producing the more valuable animal’s sperm.

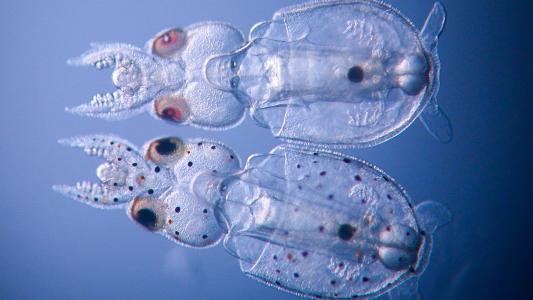

So far, only mouse surrogate sires have been bred, successfully passing on other males’ healthy descendants who are expressing only the prized genes.

There’s one massive obstacle to using this technology for cattle and other livestock, though. Current regulations would prevent any of their progeny from entering into the food supply, without jumping through the strict regulatory hoops for genetically engineered animals — although technically only the surrogate males themselves are genetically edited, not “their” offspring, who merely get another male’s natural, unmodified genes, just like with artificial insemination.

“This shows the world that this technology is real. It can be used,” Bruce Whitelaw, a member of the research team from the University of Edinburgh’s Roslin Institute, told WSU News.

“We now have to go in and work out how best to use it productively to help feed our growing population.”