Cancer immunotherapy works by turning our immune system against cancer cells, killing them off like they would an infection. While the technique can be effective, it works best for only some types of cancers, and it’s at its best when facing down cancers that are riddled with mutations.

Which is why researchers like Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s Luis Diaz have a novel, and controversial — and perhaps a little counterintuitive — proposal: purposefully inducing mutations in cancer cells so that they become even more alien-looking.

With less in common with healthy cells, the cancer should stick out as a hotter target for the immune system.

Researchers have a novel, controversial — and perhaps a little counterintuitive — proposal: purposefully inducing mutations in cancer cells so that they become even more alien-looking.

Diaz told the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research that it could be possible to purposefully “remodel” the genetics of a tumor to make the immune system attack it better, Science’s Jocelyn Kaiser reported.

But other researchers disagree, and some animal models suggest that purposeful mutation could do more harm than good. “I question the rationale,” UCLA melanoma immunotherapy researcher Antoni Ribas told Kaiser.

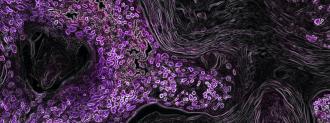

T cell targets: Immunotherapy’s frontline forces are called T cells.

When removed from a patient and outfitted with a tool called a “chimeric antigen receptor,” or CAR, these T cells will home in on unique targets from tumor cells. Then the CAR-T cells are reinfused into the patient, ready to rock.

But all T cells have receptors on them from proteins that control whether they are turned off or on, called checkpoint proteins. Some kinds of tumors make high levels of these checkpoint proteins to turn off the attacking T cells, preventing them from fighting the cancer.

Checkpoint inhibitor therapy uses drugs to block these checkpoint proteins, letting the T cells get back to business. They are commonly used as a treatment for melanoma and lung cancers. Tumors from those cancers can acquire mutations through UV light or tobacco smoke, mutations which can cause them to create more unique protein targets for the T cells to aim at, called “neoantigens.”

Previous studies in humans and mice have found that inducing an accumulation of mutations in tumors makes checkpoint inhibitors more effective, Kaiser reported.

With less in common with healthy cells, the cancer should stick out as a hotter target for the immune system.

Shifting the frame: Building off this previous work, Diaz and his colleagues turned their focus on causing a kind of super-mutation in cancer cells.

By mutating a protein that helps to correctly read messenger RNA, they could induce “frameshift mutations” in proteins the cell makes, making them look more alien to the immune system.

When the Diaz lab tested a combination of the chemo drugs temozolomide and cisplatin, which are each known to cause mutations, they found they could cause 1000x more frameshift mutations than with either drug separately.

When those heavily mutated cells were injected into mice, the tumors were eliminated by a simple round of checkpoint inhibitors.

There are multiple risks to purposefully causing mutations, including the chemotherapy combo also inducing mutations in healthy cells.

The risks: There are multiple risks to purposefully causing mutations. The chemotherapy combo could also induce mutations in healthy cells, for one thing.

Also, tumor cells that are all closely related and come from only a few cell lines may respond better to checkpoint inhibitor therapy than more diverse tumors. Another risk is creating more mutations could cause new clones to form, reducing the efficacy of the T cells that are specialized at recognizing particular antigens.

The lab is now testing the combination on a small group of patients with metastatic colon tumors before they receive any checkpoint inhibitors. Two of the 10 patients have shown the presence of a high level of frameshift mutations, and have seen their tumors’ growth halted.

“It’s early days,” Diaz told Kaiser, but are “a flavor of what we’re expecting.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].