This year, of all years, has put medicine into the forefront of the public consciousness.

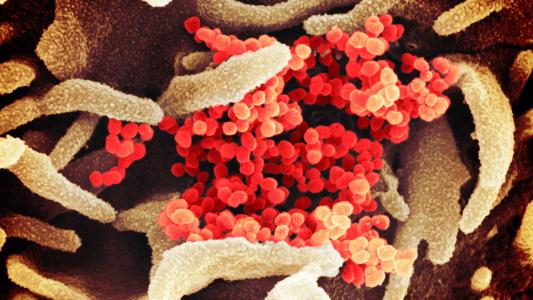

Epidemiologists, immunologists, physicians, public health officials — people who dedicated their lives to medicine giving us a call to arms, advice, and play-by-play, as an invisible enemy rocked society to its foundations.

All is not lost, however. In the proud tradition of back-to-the-wall innovation, incredible public health achievements have advanced at unthinkable speed.

And across various fields of medicine, science has continued apace, even if buried under the endless headlines about the ruthless attack of SARS-CoV-2.

Here are three medical breakthroughs, insights, and achievements that most inspired me in 2020, in no particular order.

An mRNA Based COVID-19 Vaccine

It had to be this, right? A crowning achievement for science, for biotech, for public health, not only the most awe-inspiring medical development of not only this year, but perhaps the 21st century so far.

In creating and delivering a COVID-19 vaccine in record time, medicine has achieved a stunning victory. And while it comes too late for many — with at least 1.6 million lives lost so far — it arrives sooner than most thought possible.

The dream of mRNA vaccines is not just a weapon but a weapons system. By plugging in snippets of a virus’s messenger RNA and delivering them to our cells, we can cause our cells to crank out the antigens that are necessary to achieve an immune response.

It could be a plug-and-play system, where a virus’s genetic code could be inserted into the vaccine platform to instantly create a new vaccine. (Moderna’s mRNA vaccine was created in just two days in January.)

A nimble and necessary weapon, for a virus world.

Every infectious disease expert I have ever interviewed, from Fauci on down, has had one warning: more viruses are coming, and they are coming at a faster clip. Climate change, human encroachment into new habitats, our interconnectedness; we have built a virus’s dream world, and it was only a matter of when, not if, a new virus thrived within it.

mRNA vaccines are now being rolled out to stop a pandemic that’s already out of control, a moment that just may announce a new era — the future borne in coolers, kept colder than ice.

In the proud tradition of back-to-the-wall innovation, incredible public health achievements have advanced at unthinkable speed.

I wept when it was apparent these vaccines worked. I pray they prove as efficacious as we hope, that they stay and become the human achievement they could be — the next great chapter in the book of scientific medicine, from inoculations in ancient China and the first vaccine in 1767 to the discovery of penicillin in 1928 and idoxuridine (the first antiviral) in 1962.

And I dream of a future generation, maybe the next generation, who will see our previously-plodding pace of vaccine creation and imagine it as crude and horrifying as we consider the society-scything plagues of the past.

Advancements in HIV

Speaking of viruses, one stands out as being exceptionally tricky to defeat: HIV. But new developments in 2020 have pushed us closer to a possible cure and the functional equivalent of a vaccine.

Advances in antiretroviral therapy (ART) have changed HIV infection from a veritable death sentence to a manageable, but incurable, chronic disease — for those who can access it.

Yet, we still can’t clear the virus from the body or prevent infection with a vaccine. HIV mutates so rapidly that it slips around the antibodies a vaccine would promote. And even when it’s suppressed by ART, HIV can lurk inside our cells, ready to pounce if the ART bombardment stops.

But a new study using CRISPR in monkeys may be a step towards wiping out the sneaky virus.

Researchers at Tulane delivered the gene-snipping tool CRISPR/Cas9 in monkeys infected with SIV (the monkey version of HIV). Once CRISPR hit the cells, the genetic scissors snipped out the virus’s DNA. Its plans removed, the virus wasn’t able to hijack the cells and replicate itself.

Within three weeks, SIV had been cleared from up to two-thirds of the cells in its favorite hiding spots.

That’s not the only exciting news involving HIV, CRISPR, and monkeys.

I said HIV is incurable, but that’s not quite true: two patients (out of 38 million worldwide) have been cured after receiving bone marrow transplants from donors who have a rare mutation that makes them immune to HIV.

This year, of all years, has put medicine into the forefront of the public consciousness.

Unfortunately, other transplant attempts from immune donors have failed. But University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers have now used CRISPR to successfully insert the gene for immunity into monkey embryos. The goal is eventually to be able to insert the gene into an individual’s stem cells, which could then be transplanted back into them, creating an HIV cure.

While a true HIV vaccine is currently out of reach, taking ART before exposure can prevent infections — a technique called pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). PrEP is very effective, but the downside is that it isn’t cheap — and it’s hard to remember to take a pill literally every day.

That’s why the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) is testing a long-lasting form of HIV prevention — an injectable drug, called cabotegravir, that only needs to be taken every two months.

In May 2020, a study found that the injection was at least as good as the daily pill (and probably better) in two high-risk groups: men who have sex with men and transgender women. In November, a second study proved that the bimonthly injection was way more effective than the pill in women — 89% more effective, in fact.

And note that the daily pill itself reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex by more than 90%, according to the CDC — and the injection is 89% better than that (at least in women).

That’s not a vaccine, but it’s getting a lot closer. (And 6 injections a year definitely beats 365 pills.)

DeepMind Solves a Decades-old Problem

The gauntlet was thrown down in 1972.

During his Nobel acceptance speech, biochemist Christian Anfinsen suggested that a protein’s form should determine its function. If we can predict how a protein will fold, then who knows what we could learn about life!

Science has been trying to do just that ever since, and now, in 2020, an acceptable answer has been found.

Created and trained by DeepMind, the AI AlphaFold predicted protein structures based on their genetic code, with an accuracy impossible to achieve outside of costly and time-consuming laboratory imaging methods.

Proteins are made up of 20 amino acids, and they do, well, everything in living organisms (and viruses). We know these amino acids well, and we also know their order from the protein’s DNA. But what we can’t do well is guess what they look like when folded together like origami in 3D; it’s like trying to go from a chemical recipe to a sculpture.

At least, we couldn’t — until now.

The ability to accurately and consistently predict — out of an unimaginable array of options — what a protein will look like could open up vast new worlds of knowledge.