The first-in-human trial of an experimental drug, lepodisiran, found that a single shot could dramatically and durably reduce blood levels of lipoprotein(a), a currently untreatable risk factor for heart disease.

The challenge: Your levels of LDL cholesterol — the bad kind that clogs arteries and leads to heart disease — are based on a combination of factors, including genetics, diet, and lifestyle.

That means if your LDL is too high, you can change what you eat, exercise more, or cut back on vices, like smoking and alcohol. There are also drugs, like statins, that are highly effective at lowering LDL levels.

An estimated 20% of the global population has high levels of Lp(a).

Lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a), is another particle produced by your liver, just like LDL cholesterol, and high levels in your blood independently raises your risk of heart disease. Unlike LDL cholesterol, though, your Lp(a) levels are determined almost entirely by genetics.

That means an estimated 20% of the global population who have high levels of Lp(a) can’t reduce this major risk factor for heart disease, and there aren’t any proven medicines to significantly lower Lp(a) levels, either. (To mitigate their risk, this group must be even more careful about their LDL levels, since that’s the only factor they can control.)

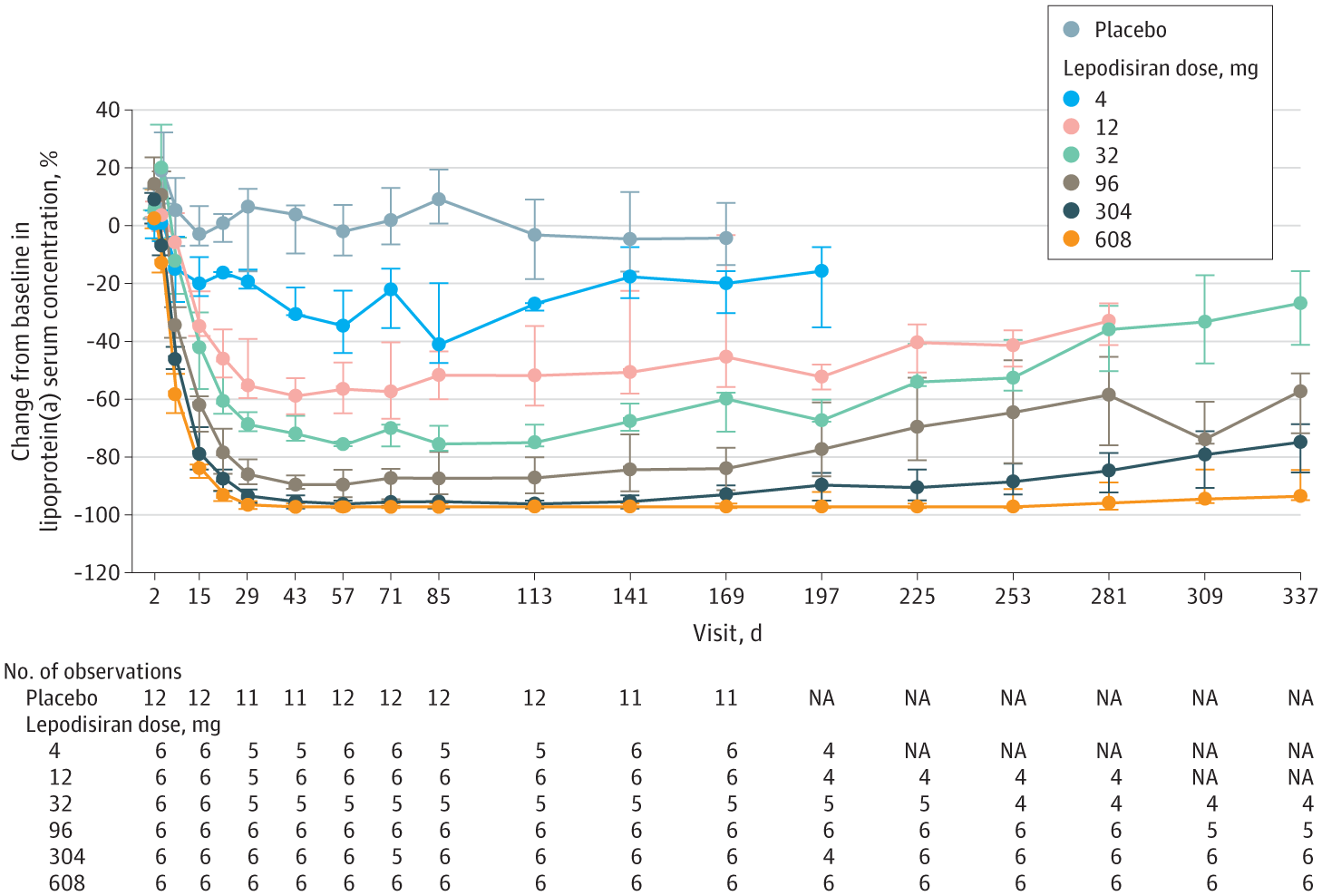

What’s new? On November 12, researchers published the results of a phase 1 trial of an experimental drug being developed by pharma giant Eli Lilly. The drug was shown to lower participants’ high Lp(a) levels by as much as 96% from their baseline.

“If further trials show that this medication — lepodisiran — is safe and can reduce heart attacks and strokes, it would be good news for patients because it eliminates a risk factor we’ve been unable to treat,” said lead study author Steve Nissen.

“Its effectiveness at lowering Lp(a) was profound.”

Steve Nissen

How it works: Lepodisiran is a small interfering RNA (siRNA), an aptly named therapy that works by interfering with RNA, the genetic material that translates your DNA into instructions for your cells to make certain molecules. The siRNA stops the RNA from being translated into proteins, essentially “silencing” a gene without affecting your DNA.

The RNA that lepodisiran targets creates an essential component of Lp(a).

“How do you beat a risk factor that’s largely genetic? One highly effective approach is to interfere with the gene, and that’s what lepodisiran and other new therapies are designed to do,” said Nissen.

After 48 weeks, their Lp(a) levels were still 94% lower than prior to the trial.

The phase 1 trial of lepodisiran included 48 people with elevated Lp(a) levels. Twelve were given a single injection of a placebo. The others were divided into groups of six, with each group given a different-sized dose of lepodisiran, ranging from 4 milligrams all the way up to 608 mg

In the highest dose group, blood Lp(a) levels were actually undetectable 29 days after the injection. They started to rise slowly after 40 weeks, but even at 48 weeks, they were still 94% lower than prior to the trial. The next-highest dosage, 304 mg, saw a 75% reduction even after 48 weeks.

No safety issues cropped up during the trial, and the only adverse effects were mild injection site pain.

Looking ahead: A phase 2 trial of lepodisiran is already underway. It’ll include more than 250 people with elevated Lp(a) levels and is expected to wrap up in October 2024.

“In our view, this therapeutic is very promising,” said Nissen. “These [phase 1] data indicate lepodisiran is safe, and its effectiveness at lowering Lp(a) was profound, with near-total elimination of Lp(a) that lasted for a long time. We’ll know more after the phase 2 study.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].