A man with complete paralysis, known as total locked-in syndrome, was able to send messages to his family after receiving a brain implant that lets him spell out sentences with only his mind.

He is the first completely paralyzed person to use a brain-computer interface (BCI) to communicate.

The challenge: Locked-in syndrome is a rare disorder in which a patient is paralyzed, but also conscious and awake — they can see, hear, and think, but can’t voluntarily move any muscles other than the ones used to blink or move their eyes up and down.

People with total locked-in syndrome have traditionally had no way to communicate with the outside world.

People with locked-in syndrome rely on that eye movement to communicate — they might blink once for “yes” or twice for “no,” for example, or use eye-tracking tech to spell out words by looking at letters on a screen.

People with total locked-in syndrome can’t even control their eyes, though. That means they’ve traditionally had no way to communicate with the outside world, or even let people know that they’re still aware and capable of thinking.

The request: In 2015, a man now known as “patient K1” lost the ability to walk or talk due to a fast-progressing form of ALS, a neurodegenerative disease. By 2017, he was starting to lose the ability to control his eye movements, too.

Anticipating that total locked-in syndrome was imminent, the man asked his family — who cared for him at home — to help him find a way to keep communicating.

They contacted neuroscientist Niels Birbaumer and neurotechnologist Ujwal Chaudhary, who were then working at the University of Tübingen.

“To our knowledge, ours is the first study to achieve communication by someone who has no remaining voluntary movement.”

Jonas Zimmermann

Birbaumer, Chaudhary, and their collaborators at the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering have now published a study detailing how they used a BCI to let the completely paralyzed man communicate with his loved ones using only his mind.

“This study answers a long-standing question about whether people with complete locked-in syndrome … also lose the ability of their brain to generate commands for communication,” said co-author Jonas Zimmermann, a Wyss Center neuroscientist.

“[T]o our knowledge, ours is the first study to achieve communication by someone who has no remaining voluntary movement and hence for whom the BCI is now the sole means of communication,” he added.

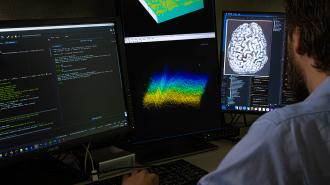

The study: The researchers started by implanting two small electrode arrays in parts of the man’s brain related to movement. Then they asked him to think about moving certain body parts while they tracked his brain activity on a computer.

The hope was that they might be able to link certain brain activity patterns to the man’s attempted movements.

If so, they could use that to create a form of communication — the man could think about moving his left leg if he wanted to answer “yes” to a question, for example, and the brain activity would reveal his intentions to the researchers through the computer.

After three months of trying, though, the brain activity still wasn’t consistent enough, so the researchers decided to try something new.

The patient communicates by using his mind to adjust the pitch of a tone: higher for “yes” and lower for “no.”

First, they set up the man’s BCI so that an audible tone would get higher if the brain neurons near his implant started firing more quickly and lower if they slowed down.

They then played a tone and asked the man to try to make a second tone (the one linked to his BCI) match its pitch using any strategy he could think of. During this process, he got real-time feedback on what (if anything) was happening to the second tone.

If he could manipulate the tones with his mind, the plan was for him to learn to create and hold a high note to say “yes” and a low note to say “no.”

The breakthrough: On the first day of trying, the patient was able to alter his tone — he told the researchers the key was thinking about moving his eyes — and by day 12, he could match the pitch of the target tone.

The researchers linked this ability to a system that reads letters out loud, and by choosing letters with his “yes” and “no” tones, the patient was able to spell out his first sentence — a request to have his body repositioned — around day 21.

Over the next year, the man spelled out dozens of sentences. Some asked for certain music or foods (“I would like to listen to the album by Tool loud” and “and now a beer”), while others were messages for the researchers or his family (“boys, it works so effortlessly” and “I love my cool son”).

The big picture: The system is far from perfect — the man was only able to spell out intelligible sentences on 44 of the 135 days reported in the study, and on 28 of the 135 days, his accuracy at matching the target tones was less than 80%.

His ability to use the device is also getting worse with time — three years after his electrode surgery, he’s now mostly limited to answering yes-no questions rather than spelling out sentences.

This is likely due to scar tissue around the implants, which reduces the brain signal quality, and possibly due to cognitive decline from ALS, according to Zimmerman.

“This is a great example of how technological advances in the BCI field can be translated to create direct impact.”

George Kouvas

This is also just a single case study, meaning it’s hard to say whether other people with total locked-in syndrome might be able to use a BCI to communicate. Even if they could, Chaudhary estimates the cost of the system to be close to $500,000 for the first 2 years.

All those caveats aside, though, the study is hugely encouraging, especially given that the man was able to use the tech while in home care.

“This is an important step for people living with ALS who are being cared for outside the hospital environment,” said Wyss Center CTO George Kouvas. “This technology, benefiting a patient and his family in their own environment, is a great example of how technological advances in the BCI field can be translated to create direct impact.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].