UK scientists have developed a new light-activated cancer treatment that could make existing therapies more effective and more targeted — potentially improving outcomes while reducing nasty side effects.

Antibody therapy: Our bodies are made up of trillions of cells that go through a life cycle of growing, dividing to form new cells, and then dying or turning off when they’re old or damaged.

Cancerous cells don’t die when they should, though. They keep growing and multiplying, crowding out healthy cells, and damaging vital systems. And because they start out like normal, healthy cells, our immune systems don’t attack them like they would with obvious invaders, like viruses and bacteria.

We can supercharge our immune defenses against cancer with lab-created antibodies that stick to proteins commonly found on cancer cells. We can even use these antibodies to deliver drugs right to tumors.

The new antibody fragment only binds to its target protein when exposed to UV light.

The problem: The proteins targeted by these antibodies also appear on noncancerous cells, though, so while antibody therapy is more targeted than traditional chemotherapy, it still damages some healthy cells and causes unwanted side effects.

Antibodies are also too large to penetrate deep into solid tumors, and while smaller antibody fragments can be designed to get in there, they tend to detach from their targets and leave the body sooner, minimizing their efficacy.

A light-activated cancer treatment: University of East Anglia researchers have now developed a new antibody fragment that only binds to its target protein when exposed to a specific wavelength of UV light — and then it forms a permanent “covalent bond” with the cell.

“A covalent bond is a bit like melting two pieces of plastic and fusing them together,” said Amit Sachdeva, the study’s principal scientist.

The light therapy could solve two problems: antibody fragments failing to stick to tumors, and antibodies going off target and targeting healthy cells, far from the tumor.

“This would allow cancer treatment to be more efficient and targeted.”

Amit Sachdeva

Sachdeva says doctors could use these antibody fragments to deliver drug molecules that would permanently attach to cancer cells, using implantable LED lights placed in or near the tumors to make the treatment more targeted.

In the case of skin cancer, a light could be shone on the cancer outside the body after the antibody fragments are administered.

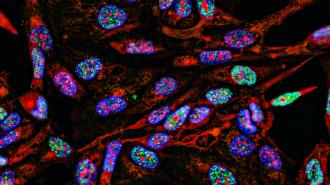

Looking ahead: So far, the UEA researchers have demonstrated in lab tests that their antibody fragment will bind to EGFR, a protein commonly found on cancer cells, when activated by light.

Sachdeva expects it’ll be another 5 to 10 years before the light-activated cancer treatment could be ready for human trials, but if it does clear the development process, he believes it could revolutionize cancer therapy.

“This would allow cancer treatment to be more efficient and targeted because it means that only molecules in the vicinity of the tumour would be activated, and it wouldn’t affect other cells,” he said. “This would potentially reduce side effects for patients, and also improve antibody residence time in the body.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.