A new treatment that caused diseased kidneys to regenerate in mice might soon do the same for people, according to its developers at the Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School.

“The therapy could be used to treat people at risk of acute kidney disease to prevent it, to treat people who have acute kidney disease to reduce kidney damage, and to treat patients with established chronic kidney disease to reverse it,” principal investigator Stuart Cook told the Straits Times.

The challenge: Regeneration isn’t just for sci-fi shows and lizards — parts of the human body have regenerative abilities, too. Doctors can remove up to two-thirds of a person’s liver, for example, and the remaining bit will regenerate until the organ is full-sized again.

Our kidneys have some regenerative abilities, too, but not enough to overcome serious disease or damage — people with kidney damage often have to go on dialysis for the rest of their lives or seek a transplant. Even with a compatible donor, patients have to go on immune-suppressing drugs for the rest of their lives to prevent rejection.

“This discovery could be a real game-changer in the treatment of chronic kidney disease.”

Thomas Coffman

What’s new? Led by scientists at Duke-NUS Medical School, an international team of researchers has now uncovered the mechanism that stifles regeneration in damaged kidneys and demonstrated a way to restore the ability — in mice.

They claim this is the first time a treatment has led to the regeneration of a diseased kidney.

“This discovery could be a real game-changer in the treatment of chronic kidney disease … bringing us one step closer to delivering the benefits promised by regenerative medicine,” said Thomas Coffman, dean of the Duke-NUS Medical School.

“Anti-IL11 therapy can treat kidney failure, reverse established chronic kidney disease, and restore kidney function.”

Stuart Cook

How it works: Past studies have linked the protein interleukin-11 (IL-11) to scarring in other organs, so the team started their research by looking at the role it plays in the kidneys.

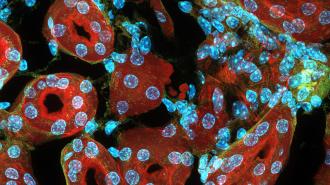

They discovered that kidney damage causes renal tubular cells — cells that line the tubes inside the kidneys — to release IL-11. This increases the expression of a gene that stops those cells from growing and leads to kidney dysfunction.

To try to neutralize this effect, the team administered an antibody that binds to IL-11 in mouse models of human kidney disease, twice a week for six weeks. At the start of treatment, the rodents’ kidney function was reduced by about a third, and their kidneys had lost about a third of their mass.

Three months after beginning treatment, the mice had regained about 50% of their lost kidney mass and function. That was when the study ended, so it’s possible they might have improved further over time.

“[We showed that] anti-IL11 therapy can treat kidney failure, reverse established chronic kidney disease, and restore kidney function by promoting regeneration in mice, while being safe for long term use,” said Cook.

“The cost of giving a drug that prevents someone going onto kidney dialysis is very small compared with the cost of dialysis itself.”

Stuart Cook

Looking ahead: The researchers told the Straits Times that they’ve tested the antibody in older mice with kidney disease, younger mice with kidney disease and diabetes, and human cells in the lab, all with the same positive results (though that research has yet to be published).

They plan to launch safety trials of the antibody in people in 2023, and if those go well, they hope to begin clinical trials within the next two to three years. If the drug is ultimately approved for use, Cook expects it to be “reasonably expensive,” but cheaper than the alternative.

“The cost of giving a drug that prevents someone going onto kidney dialysis is very small compared with the cost of dialysis itself,” he said.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.