Memories are stored in all different areas across the brain as networks of neurons called engrams. In addition to collecting information about incoming stimuli, these engrams capture emotional information. In a new study, Steve Ramirez, a neuroscientist at Boston University, discovered where the brain stores positive and negative memories and uncovered hundreds of markers that differentiate positive-memory neurons from negative-memory neurons.

In 2019, Ramirez found evidence that good and bad memories are stored in different regions of the hippocampus, a cashew-shaped structure that holds sensory and emotional information necessary for forming and retrieving memories. The top part of the hippocampus activated when mice underwent enjoyable experiences, but the bottom region activated when they had negative experiences.

His team also found that they could manipulate memories by activating these regions. When he and his team activated the top area of the hippocampus, bad memories were less traumatic. Conversely, when they activated the bottom part, mice exhibited signs of long-last lasting anxiety-related behavioral changes. Ramirez suspected this difference in effect was because the neurons that store good and bad memories have different functions beyond simply keeping positive and negative emotions. However, before he could unravel this difference, he needed to identify which cells were storing good and bad memories. The results were published in the journal Communications Biology.

Positive and negative memories

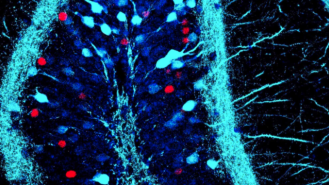

To determine where positive and negative memories were being stored, Ramirez and his team genetically modified mouse neurons to glow red or green when activated. When the mice were undergoing a traumatic experience (that is, creating a bad memory), the researchers prevented the green protein from being expressed, and when the mice were undergoing a positive experience (that is, creating a good memory), the researchers blocked the red protein. In this way, neurons that stored bad memories would glow red, and neurons that stored good memories would glow green.

They found that some areas of the brain (notably the prefrontal cortex, the region responsible for orchestrating thoughts and actions according to internal goals) contained red and green fluorescent signals, indicating that they hosted positive and negative memory-storing neurons. Notably, other regions primarily hosted only one type. For example, some parts of the amygdala (which is involved in emotional information processing) primarily hosted neurons that stored positive memories, whereas other areas of the amygdala primarily hosted neurons that held negative memories.

“That’s pretty wild because it suggests that these positive and negative memories have their own separate real estate in the brain,” said Ramirez in a statement.

Good and bad memory cells work differently

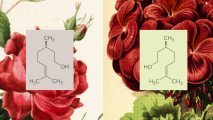

Since the positive and negative engrams store different types of memories and reside in distinct brain regions, the researchers suspected that they could be distinguished molecularly. To catalog these differences, they compared the RNA of neurons activated while creating positive and negative memories to neurons activated when storing a neutral memory. Negative-memory neurons expressed 212 genes that neither positive-memory nor neutral-memory cells expressed, and positive-memory neurons expressed 872 genes that neither negative-memory nor neutral-memory cells expressed. This suggested that positive and negative-memory neurons possess distinct molecular mechanisms.

This potentially has an enormous implication: It opens the door to exploring memory manipulation. Ramirez added, “We want game changers, right? We want things that are going to be way more effective than the currently available treatment options.”

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.