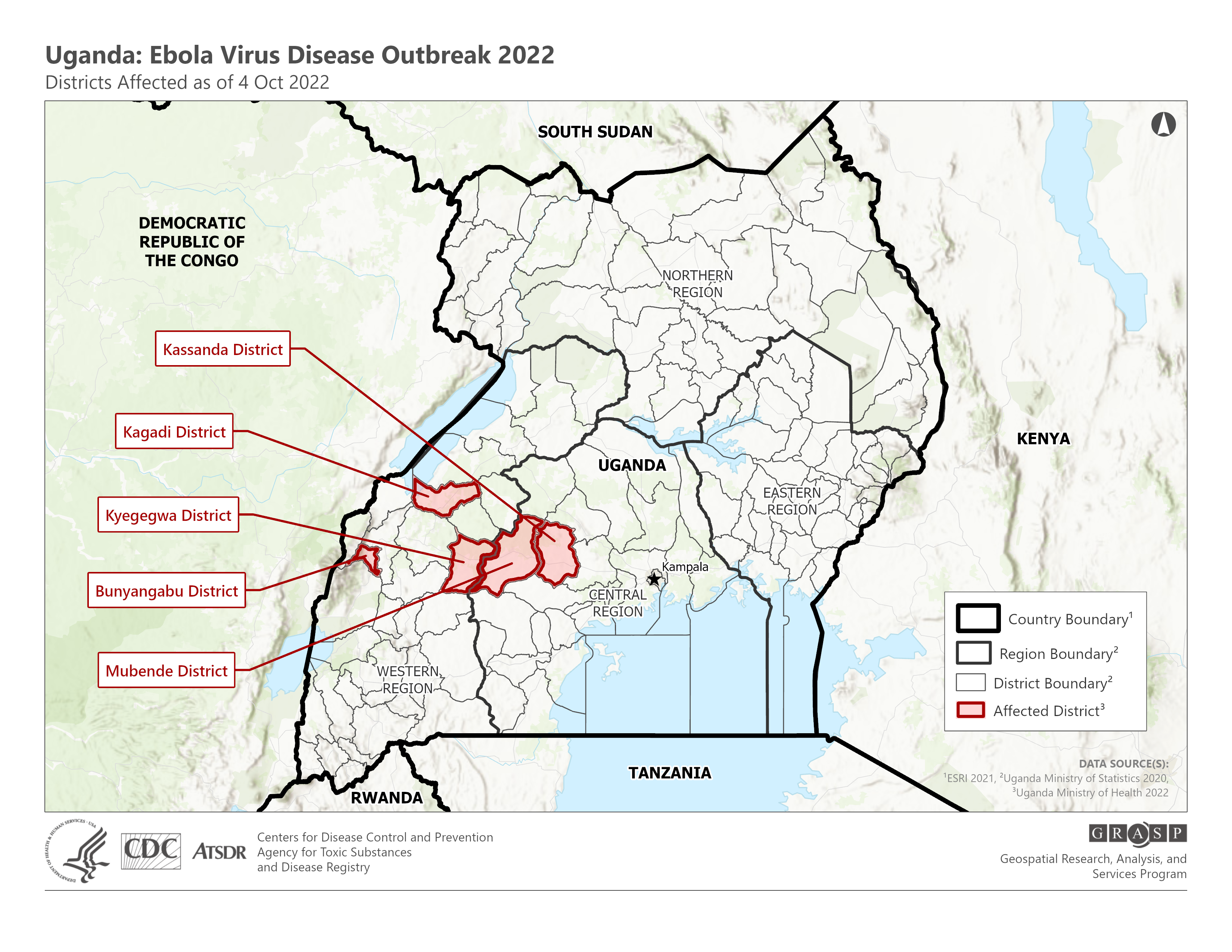

Since rearing its head in Uganda in late September 2022, the Ebola Sudan virus has caused 54 confirmed cases and 19 deaths, the country’s health ministry says. On October 12, health minister Jane Ruth Aceng confirmed the discovery of a case in the capital of Kampala, a metropolis of millions, Reuters reported.

Recent Ebola outbreaks in the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where the virus is endemic, have been successfully snuffed by new vaccines. But those same vaccines — as well as recent advances in antiviral therapies — are only approved for one strain of the virus, Ebola Zaire.

Sometimes, if we’re lucky, vaccines and drugs targeting one strain of a virus provide at least partial protection against related strains. This, unfortunately, is not likely to be one of those times.

A virus by any other name: While COVID-19 variants have us watching Greek letters like a pledge during rush week, the multiple strains of Ebola aren’t quite analogous to SARS-CoV-2’s variants of concern.

“It’s a little different,” Thomas Geisbert, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Texas Medical Branch, tells Freethink. The genetic distance between SARS-2’s variants is much smaller than the differences between Ebola strains.

“They’re different by maybe 37 to 41%,” Geisbert says. “So, they’re much more diverse than what you would think about with SARS-CoV-2 strains.”

Geisbert’s biosafety lab at UTMB specializes in studying the viruses behind a brutal class of diseases called “viral hemorrhagic fevers,” including Lassa virus, Ebola, and Ebola’s noodly relative Marburg virus, and he also helped to construct the world’s first Ebola vaccine.

So he knows that the vaccines and antivirals that have helped contain Ebola Zaire in the Congo likely cannot be relied upon here.

“The vaccines and treatments that are licensed for Ebola Zaire right now won’t work against Ebola Sudan,” Geisbert says, although he notes he cannot be 100% certain. (Welcome to immunology.)

While there are successful vaccines and antivirals available, they are only approved for Ebola Zaire, not Ebola Sudan, the strain causing an outbreak in Uganda.

Trial by fire: Fortunately, Geisbert and other researchers have developed vaccines and drugs that could potentially fight Ebola Sudan. But currently, nobody is allowed to use them.

“There are vaccines, but they just haven’t been licensed,” Geisbert explains; the same goes for antivirals.

To get licensed, regulators typically want to see efficacy data, but testing these kinds of drugs can be hard. The virus is too rare for a timely phase 3 trial, and you can’t exactly expect someone to sign up for a human challenge trial of Ebola Sudan, which has a case fatality rate of 40-60%.

That means that researchers have to gauge vaccine and antiviral effectiveness using other models — in Ebola Sudan’s case, non-human primates like monkeys, which are the best animal model for Ebola infection.

But Uganda’s recent outbreak offers a unique opportunity to test vaccines and antivirals in the real world. If the country agrees, the most promising candidates could be deployed to help fight the outbreak, in a kind of trial-by-fire.

STAT’s Helen Branswell reported on September 29 that the WHO and Ugandan government have already been meeting about just that, with Uganda already nominating a principal investigator to run the study.

WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, commenting on the discovery of Ebola in Kampala, said clinical trials of vaccines could take place within weeks, Reuters reports, although he did not detail which vaccines they would be.

Geisbert is confident we’re not helpless against Ebola Sudan, but we do need to find out how well our defenses work.

Current treatments and vaccines may not work against Ebola Sudan, as Ebola strains are quite different from each other.

The vaccines: There are multiple Ebola Sudan vaccine designs out there, at various levels of readiness. Perhaps furthest along, the WHO’s Ana Maria Henao-Restrepo told Branswell, is one at the Sabin Vaccine Institute.

The Sabin vaccine is based on a cold-like virus called an adenovirus that infects chimpanzees, ChAd3. The adenovirus is modified to express Ebola Sudan’s glycoprotein, a protein found on the outside of the virus. This primes the immune system to create antibodies against that protein, providing protection against Ebola Sudan.

There are two other vaccine candidates that use adenoviruses, Branswell reported.

Adenovirus vectors have some potential drawbacks, however. Rare but serious side effects have been associated with previous adenovirus vaccines, such as the rare clotting disorders linked to the Oxford-AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccines.

Even if similar risks are discovered here, that’s not necessarily a dealbreaker — regulators decided the benefits of the COVID-19 vaccines outweighed the risks, and Ebola is much deadlier than COVID-19.

Fortunately, researchers have developed vaccines and drugs that could potentially fight Ebola Sudan.

But adenovirus vaccines also run into another problem: people may have already been exposed to the viruses on which they’re based.

“If it’s something out there in nature, people already have antibodies against it,” says Geisbert, who is an unpaid, non-UTMB affiliated consultant to the WHO for the current outbreak.

And if you have antibodies against the vector, your body may neutralize the virus before it has a chance to react to the Ebola protein that’s tacked onto it.

Using a chimpanzee adenovirus instead of a human one helps, but since chimpanzees and Ebola have overlapping home ranges, that could still present a problem in this case. Surveys have found that up to 15% of the population in some regions have antibodies to some of these viruses, Geisbert says (although noting he is not aware of surveys on ChAd3 specifically).

The approved Ebola Zaire vaccine that Geisbert helped lay the groundwork for, Merck’s ERVEBO, is based on a different virus. Called “recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus” (rVSV), it is a virus that infects livestock, not people.

“One of the cool things about it is that humans don’t really get it,” Geisbert says. Unless you’re a researcher who accidentally catches it in the lab, you likely won’t have any antibodies to it.

Much like the mRNA and adeno-vector vaccines, the bullet-shaped rVSV is also a platform — swap out the target it’s carrying, and you’ve got a new vaccine. Geisbert’s team has done just that, inserting Ebola Sudan’s glycoprotein into the earlier vaccine.

This vaccine has already demonstrated strong efficacy in monkeys — even when it was given immediately after exposure.

The rVSV in the vaccine is also capable of replicating, which may cause a more durable immune response as the body continues to recognize it. Safety tests suggest the replication isn’t a likely cause for concern; even in immunocompromised monkeys, the vaccine did not make them sick.

The virus’ rarity and lethality make it difficult to get the data needed for vaccine and drug approval.

The antivirals: Perhaps the most promising antiviral against SUDV is Mapp Biopharmaceuticals’ MBP134.

“If I had a lab accident, I’d be on the phone trying to call Mapp Bio and trying to get MPB134,” Geisbert says.

The drug is a cocktail of two different antibodies made in a lab — called monoclonal antibodies, or mAbs — that take aim at Ebola Sudan’s glycoprotein.

MBP134 has rescued non-human primates infected with Ebola Sudan, as well as Ebola Zaire and another Ebola strain called Bundibugyo virus, Mapp co-founder and president Larry Zeitlin tells Freethink.

Zeitlin says the drug’s attack is two-pronged: not only does MBP134 neutralize the virus on its own, but it may also call in the immune system to help kill off infected cells.

“To date, the antibodies of MBP134 have been shown to be active in cell culture to all ebolaviruses and effective in non-human primate models for the three ebolaviruses that have been tested,” Zeitlin says.

The federal Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) recently awarded Mapp a $109.8 million contract to help get MBP134 across the finish line, including manufacturing, safety and efficacy testing, and regulatory submission support.

As part of the contract, Mapp will also create a freeze-dried version of the antiviral, to help make it as accessible as possible.

“If approved this treatment will put the U.S. in a better position to prepare for and respond to future potential ebolavirus incidents,” Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response Dawn O’Connell said in a statement.

“Given the current outbreak of Ebola Sudan in Uganda, this work is now even more important.”

Uganda’s outbreak may be a trial-by-fire for new Ebola Sudan vaccines and therapies.

Being ready: As the outbreak continues to grow, Ebola Sudan treatments with strong clinical evidence are waiting in the wings, ready — hopefully — to stem the virus’s deadly sortie.

Once considered lethal but limited, the massive 2014-2016 Ebola Zaire outbreak in West Africa — which claimed the lives of over 11,000 people across Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone — proved the virus’s devastating potential, a lesson that still haunts those involved in fighting it who I’ve interviewed in the past.

And just because it is not the same strain does not mean that Ebola Sudan — or another close relative — is incapable of similar devastation, Geisbert points out.

“We’ve got to be better prepared.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].