A new fully implantable chemo pump could help doctors get more cancer-killing meds directly to the site of a brain tumor, without increasing its side effects.

The challenge: Glioblastoma is a fast-growing, aggressive type of brain tumor. The average survival time after diagnosis is 12 to 18 months, and only 5% of patients live for five or more years after they’re diagnosed.

Glioblastoma treatment usually starts with surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible, followed by chemo or radiation to kill any remaining cancer cells — but this approach is far from ideal.

“The tumors inevitably grow back.”

Jeffrey Bruce

While radiation therapy destroys cancer cells, it can damage healthy ones in the area, too, and because chemo is usually delivered via pills or intravenously, the drugs have to travel through the body to the brain, causing side effects all along the way.

Once the chemo drugs reach their destination, the blood-brain barrier — a natural defense designed to keep microbes in the blood out of the brain — blocks most of them. This prevents the chemo from being able to effectively kill the cancer cells.

Increasing the dosage to get more of the drugs into the brain isn’t an option — the side effects would be too severe for patients to tolerate.

“The tumors inevitably grow back,” said Jeffrey Bruce, co-director of the Brain Tumor Center at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “And when they grow back, there’s no proven treatment for them.”

“If you pump in the drug very slowly … it penetrates into the brain tissue.”

Jeffrey Bruce

Pump it up: Bruce and his colleagues have now developed an implantable chemo pump that administers the drugs directly to the site of a brain tumor. In a small phase 1 trial, it worked as hoped, saturating the area around the tumor in five people with recurrent glioblastoma.

“If you pump in the drug very slowly, literally at several drops an hour, it penetrates into the brain tissue,” says Bruce. “The drug concentration that ends up in the brain is 1,000-fold greater than anything you are likely to get with intravenous or oral delivery.”

How it works: For the Columbia trial, a chemo pump was implanted into each patient’s abdomen. A thin, flexible catheter was then surgically implanted into the area of the brain where residual cancer cells might be located and connected to the pump under the patient’s skin.

Using a needle, the researchers can fill the chemo pump with whatever med they wanted — for this trial, they went with topotecan, a chemo drug typically used to treat lung cancer that had shown promise as a glioblastoma treatment in their previous research.

“The drug concentration that ends up in the brain is 1,000-fold greater.”

Jeffrey Bruce

Over the course of a month, the patients received four topotecan treatments, with the researchers using wireless technology to repeatedly turn the chemo pumps on for two days, and then off for five.

“The patients were walking, talking, eating — doing all of their normal daily activities,” said Bruce, who added that the patients couldn’t tell when the pump was delivering the drugs and when it was off.

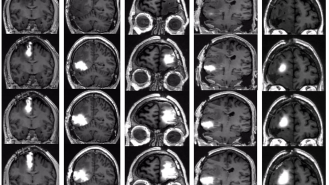

The results: Remarkably, none of the participants experienced serious neurological complications, while MRI scans revealed that the chemo pump had effectively saturated the area around their cancer with the drug.

While the trial was too small to determine whether the treatment could help patients live longer, biopsies of participants’ brains before and after treatment revealed that it significantly decreased the number of actively dividing tumor cells — without affecting their normal brain cells.

Looking ahead: For future trials of the chemo pump, the researchers hope to work with people who are experiencing glioblastoma for the first time, rather than going through a recurrence.

“A lot has already happened to make the tumor harder to treat by the time initial therapies fail, so we think that the pump will work even better with the newly diagnosed patients,” said Bruce.

“This approach would give us the ability to change the treatment over time and consider using other types of chemotherapy that would not be effective if given systemically but may be much more effective when delivered directly to the brain,” he continued.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.