Bears, bats, and colorectal cancer have one thing in common: they hibernate. According to new research out of Canada’s Princess Margaret Cancer Center, these cancer cells hibernate to evade cancer treatments.

“We never actually knew that cancer cells were like hibernating bears,” Princess Margaret’s Aaron Schimmer said in a press release.

“This study also tells us how to target these sleeping bears so they don’t hibernate and wake up to come back later, unexpectedly. I think this will turn out to be an important cause of drug resistance, and will explain something we did not have a good understanding of previously.”

A Nefarious Nap

Hibernation is marked by a greatly reduced metabolism and lowered body temperature, an energy-saving measure to help animals survive the winter.

The researchers, led by Catherine O’Brien, found that human colorectal cancer cells hibernate in much the same way. They slow their rapid cell division — basically cancer’s hallmark characteristic — to survive a different kind of brutal environment: chemotherapy.

“There are examples of animals entering into a reversible and slow-dividing state to withstand harsh environments,” O’Brien said in the release. “It appears that cancer cells have craftily co-opted this same state for their survival benefit.”

The team’s study, published in Cell, is the first to suggest that cancer cells hibernate by co-opting a natural process found in over 100 species of mammals, designed to protect embryos in challenging environments, from food scarcity to extreme temperatures.

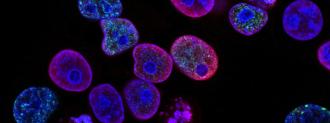

Human colorectal cancer cells were treated chemotherapy in vitro. In response, the cancer cells entered a sluggish state, slowing their usually prodigious division and requiring little nutrition. The team found that the cancer cells hibernate like this until the chemo is removed, and then return to their voracious state.

O’Brien was inspired by a talk given a few years ago about mouse embryos entering a state of hibernation to survive. They do so using a cellular mechanism called autophagy — cellular self-cannibalism. The cells breakdown their own proteins and pieces for energy, essentially surviving off of themselves — like fat bears — until the threat passes.

You can’t hibernate like this, but evidently, humans still have the genes that make it possible.

“The cancer cells are able to hijack this evolutionarily conserved survival strategy, even as it seems to be lost to humans,” O’Brien said.

Catch ’em Sleeping

While protecting them from chemo, the period where cancer cells hibernate could also provide a target for treatment.

“This gives us a unique therapeutic opportunity,” O’Brien said.

“We need to target cancer cells while they are in this slow-cycling, vulnerable state before they acquire the genetic mutations that drive drug-resistance. It is a new way to think about resistance to chemotherapy and how to overcome it.”

When O’Brien inserted a miniscule molecule that stops autophagy into the colorectal cancer cells’ petri dish, the cells didn’t survive; the chemotherapy took them out without their hibernation mode to protect them.

Adding autophagy-inhibitor drugs to chemo regimens could prevent hibernating cancer cells from surviving their nap to wreak havoc again — or evolving to become resistant to the chemo.

We just may be able to catch cancer sleeping.