A new brain cancer vaccine can extend some glioblastoma patients’ lives by months or even years, according to its maker — but the design of the company’s trial has some questioning the claims.

The challenge: The standard treatment for glioblastoma — the most aggressive form of brain cancer — starts with surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible. After that, patients typically undergo chemotherapy and radiation therapy to kill lingering cancer cells.

But even with treatment, the prognosis for glioblastoma isn’t great — the cancer almost always comes back, and patients live an average of just 12 to 18 months after diagnosis.

A brain cancer vaccine: US biotech company Northwest Biotherapeutics has developed a brain cancer vaccine, called DCVax, that’s designed to help a patient’s own immune system target their tumor.

“The vaccine … provides a personalized solution, working with a patient’s immune system.”

Keyoumars Ashkan

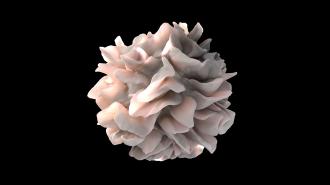

To deliver the treatment, doctors remove special types of immune system cells, called dendritic cells, from a patient’s blood sample. The cells are then mixed with antigens taken from a sample of the patient’s own tumor.

When the dendritic cells are injected back into the patient, they teach the rest of the immune system to recognize and attack the tumor cells.

“The vaccine … provides a personalized solution, working with a patient’s immune system, which is the most intelligent system known to man,” Keyoumars Ashkan, the European chief investigator of a phase 3 DCVax trial, told the Guardian.

The trial: For the trial, more than 300 newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients were treated with either the brain cancer vaccine or a placebo after standard treatment (surgery to remove their tumor, when possible, followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy).

That is a very typical trial design. But placebo group members whose cancer returned during the course of the trial were also given the option to receive the vaccine.

When the vast majority of the placebo group chose to get the treatment, the researchers had to find a different comparison group, which wasn’t part of the study.

One trial participant lived for more than 8 years after diagnosis

In the end, 13% of all trial participants treated with DCVax lived for more than five years after diagnosis, compared to 5.7% in the comparison group used for the study, which consisted of more than 1,300 patients from the control groups in other, previous glioblastoma trials.

One trial participant lived for more than 8 years after diagnosis.

According to Ashkan, DCVax produced “clear benefits” in patients who typically have a poorer prognosis, such as older people, and it was well-tolerated, too — just five trial participants reported significant adverse effects that might have been related to the treatment.

“The total results are astonishing,” said Ashkan. “The final results of this phase three trial … offer fresh hope to patients battling with glioblastoma.”

The controversy: Not everyone agrees with that assessment — Donald O’Rourke, a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Pennsylvania, who wasn’t involved with the trial, told STAT he found the data to be “unpersuasive,” in part due to how the study was conducted.

Before Northwest Bio began administering the treatment to people in their placebo group, it found that the median time it took for tumors to return was 6.2 months in treated trial participants and 7.6 months in untreated participants.

That means tumors came back sooner in people who received the brain cancer vaccine than those who received the placebo.

“The more analyses that are done post-hoc, the greater chance of finding results by chance.”

Merit Cudkowicz

The decision to compare the trial data to external controls wasn’t made until after the trial had already started. When the terms of an analysis are defined after results have already been seen, it’s called a “post-hoc analysis,” and it’s a controversial way to assess a treatment’s efficacy.

“The more analyses that are done post-hoc, the greater chance of finding results by chance — meaning that they are not true results,” Merit Cudkowicz, the chief of neurology at Mass General Hospital, who wasn’t involved in the study, told the ALS Therapy Development Institute.

Linda Liau, principal investigator of the DCVax study, defended the decision to STAT, noting that, because two-thirds of the people in the placebo arm eventually opted to received DCVax, researchers didn’t have enough people left in that group to conduct a traditional, randomized clinical trial.

“Many clinical trials reported in the literature use external case controls, which is just a different level of evidence than the traditional, randomized controlled trials,” she said.

The bottom line: By giving people in the placebo group an opportunity to receive DCVax when their cancer came back, the trial researchers gave them another shot at fighting their deadly disease — but in doing so, the trial ceased to be a simple comparison of treatment and placebo, muddying the results.

Despite the initial results — that showed tumors returned sooner with DCVax — the brain cancer vaccine could still be a worthwhile glioblastoma treatment. It might lead to better outcomes when paired with another treatment, for example, or work particularly well in certain types of cancer patients.

To find out, though, Northwest Bio will need more trials, designed in such a way that the results are indisputable.

Editor’s Note, 11/28/22, 10:35 a.m. ET: This article was updated to clarify that the decision to offer the vaccine to people in the placebo group was made prior to the start of the trial.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.