An FDA-approved heart medication boosted the efficacy of a melanoma treatment in mice. If the results translate to people, it could be a safe, simple way to improve our ability to stop the deadliest skin cancer.

The challenge: Melanoma is relatively rare, accounting for just 100,000 of the estimated 3.5 million skin cancers diagnosed in the US every year. However, it’s also the type of skin cancer most likely to grow, spread to other parts of the body, and lead to death.

About 50% of melanomas have mutations in the BRAF gene. The altered proteins produced by the mutations aid the cancer’s growth, so doctors will sometimes treat these cases with drugs called “BRAF inhibitors.”

Cancer is wily, though, and can develop resistance to BRAF inhibitors — this might make the treatment ineffective or allow the melanoma to come back later.

“Many patients do not respond optimally to these treatments.”

Berta Sánchez-Laorden

What’s new? Researchers in Spain have now demonstrated that combining a BRAF inhibitor with ranolazine, a heart medication, prevents melanoma from developing resistance in lab tests and makes BRAF inhibitors more effective in mouse models.

“Immunotherapy has established itself as a fundamental therapeutic strategy for melanoma and other types of cancer,” said researcher Berta Sánchez-Laorden. “Despite this, many patients do not respond optimally to these treatments.”

“This work shows the beneficial impact of the combination of ranolazine with immunotherapy in preclinical models of melanoma, thus supporting its possible application in patients,” she continued.

How it works: The Spanish researchers suspected that an increase in “fatty acid oxidation” (FAO) — the process where cells turn fats into energy — was key to the ability of melanoma cells to resist BRAF inhibitors.

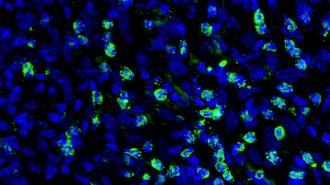

They treated melanoma cells with a high dose of the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib for a week until only “persister” cells — cells that temporarily enter a dormant state to resist treatment — remained. They then treated those with a lower dose of the cancer med for four weeks.

When they then examined the drug-resistant cells that were left, they noted signs of increased FAO, confirming their suspicions.

“RANO significantly reduced tumor growth, delayed the onset of resistance, and increased progression-free survival.”

Redondo-Muñoz et al.

Next, they treated a new batch of melanoma cells with vemurafenib and ranolazine (RANO), a medication that partially inhibits fatty acid oxidation to treat chronic chest pain caused by too little oxygen in the heart. This “profoundly reduced” the development of cells resistant to the BRAF inhibitor.

To see if treating with RANO from the jump was necessary, the researchers ran the experiment again, this time waiting until two weeks after the development of persister cells to treat the cancer cells with RANO, and the FAO inhibitor was still effective.

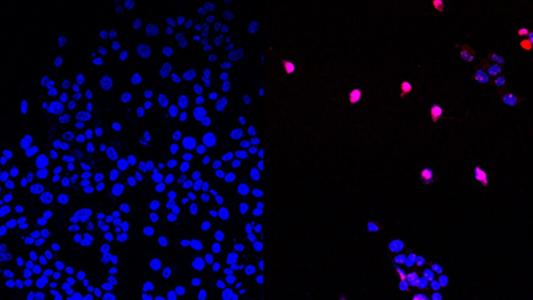

Next, they treated mouse models of melanoma with vemurafenib until their first tumors stopped responding to the BRAF inhibitor. They then split the mice into two groups, giving one vemurafenib and RANO and the other vemurafenib and a placebo.

“Strikingly, the addition of RANO significantly reduced tumor growth, delayed the onset of resistance to vemurafenib, and increased progression-free survival,” the authors write.

“The next challenge is to demonstrate the clinical effect of these combinations in patients.”

Imanol Arozarena Martinicorena

Looking ahead: Promising results in mice often don’t translate to people, so more research is necessary, but given that RANO is a well-tolerated, FDA-approved medication, it should be easier and faster to get clinical trials in cancer patients going than if it were a brand-new drug.

“This study demonstrates that it is possible to pharmacologically reorganize the metabolism of the tumor cell to improve the effect of targeted therapies and immunotherapies,” said Imanol Arozarena Martinicorena, who coordinated the research.

“The next challenge is to demonstrate the clinical effect of these combinations in patients and study the potential of ranolazine in other types of cancer,” he continued.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].