Massive trauma of the kind suffered by burn victims may require a skin graft for treatment. Essentially an organ transplant — albeit from yourself — the procedure originally involved taking skin from one part of the body and moving it to another.

The rise of 3D bioprinting, which uses the patient’s cells as a medium, now allows for sheets of artificial skin to be printed for surgeons to use. This sci-fi-seeming skin graft advancement has a major drawback, however: the sheets it produces are flat and with open edges — ill-adapted to the geometry of the body.

Think of it like trying to wrap an awkwardly shaped present with a simple rectangular wrapping paper sheet, with the maddening melange of folds, tape, and creative cutting.

3D bioprinting allows for sheets of artificial skin to be printed for grafts. There is a major drawback, however: the sheets it produces are flat and with open edges — ill-adapted to the geometry of the body.

Researchers at Columbia are looking to improve these poorly fitting, off-the-rack grafts by approaching them instead as “biological clothing” — bespoke tailored skin, shaped to the curvature of whatever body part needs it.

“As a bioengineer, it’s always bothered me that the skin’s geometry was overlooked and grafts have been made with open boundaries, or edges,” Hasan Erbil Abaci, assistant professor of dermatology at Columbia and the lead developer of the grafts, said.

“We know from bioengineering other organs that geometry is an important factor that affects function.”

A custom-tailored skin graft: The researcher’s skin grafts, published in Science Advances, begin as all custom-tailored pieces do: with accurate measurements.

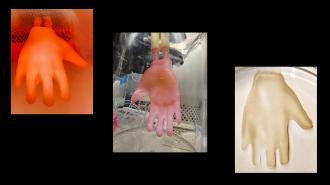

A 3D laser scan of the graft site — like a hand — is then used to create a 3D-printed, hollow model.

The outside of the model is studded with fibroblasts (cells which make skin’s connective tissue) and collagen (a protein important for structure). On top of this comes a mixture of the cells that form the outermost layer of skin. The hollow inside of the model is then filled with a growth medium, sparking the development of the cells outside of it — eventually creating a skin graft in the model’s shape.

Imagine, then, the modeled graft being slipped over the patient’s burnt hand like a glove.

Only the 3D model is unique; the rest of the process uses regular skin graft printing methods, and takes the same amount of time, roughly three weeks.

Researchers are looking to improve these off-the-rack grafts by approaching them instead as “biological clothing” — bespoke tailored skin, shaped to the curvature of whatever body part needs it.

“Like putting a pair of shorts on mice”: To test their bespoke skin grafts, which they’ve dubbed “wearable edgeless skin constructs (WESC)s,” the team grafted WESCs derived from human cells to the rear limbs of mice.

“It was like putting a pair of shorts on the mice,” Abaci said. “The entire surgery took about 10 minutes.”

Four weeks post-surgery, the skin grafts had integrated with the surrounding mouse tissue, with full range of motion.

A better fit: The team believes their modified technique can improve patient outcomes, both medically and aesthetically.

“Three-dimensional skin constructs that can be transplanted as ‘biological clothing’ would have many advantages,” Abaci said. “They would dramatically minimize the need for suturing, reduce the length of surgeries, and improve aesthetic outcomes.”

“It was like putting a pair of shorts on the mice. The entire surgery took about 10 minutes.”

Hasan Erbil Abaci

A geometrically molded skin graft was found to be stronger mechanically than using edged sheets, the researcher said. Abaci believes facial transplants could be a “compelling use,” as the tailored grafts could be laid over existing tissues as an alternative to cadaver donors.

Beyond their role as a skin graft, the WESCs could potentially be used for “drug development, cosmetics testing, and studies of fundamental skin biology,” the authors wrote in their study.

More research will be needed to match the complexity of natural skin, including pigmentation and, for in vitro studies, a functioning immune system.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].