This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

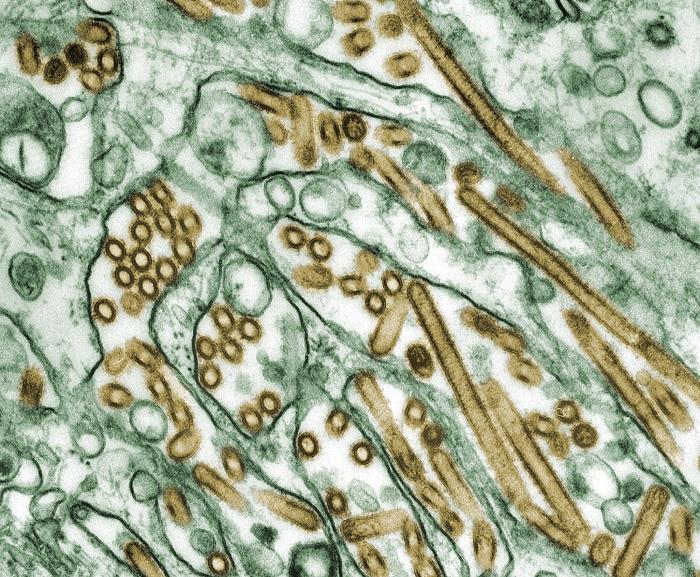

On April 5, the CDC issued a health alert informing the public and the medical community that a person in the US had contracted avian flu — something that had only happened once before. Less than a week earlier, the virus had been spotted in herds of dairy cows in the US.

So, how worrying is it that “bird flu” jumped to a person — and what can we do to stop the virus from becoming a bigger problem in the future?

Bird flu basics

There are four types of influenza viruses: A, B, C, and D. Type A and B viruses regularly infect people, and certain type A viruses can infect birds, pigs, dogs, and several other species, too.

Usually, a subtype of influenza that infects one species doesn’t readily infect another, but as the virus spreads, it can mutate or recombine with other flu viruses in ways that allow it to make the jump to a new species. In March 2024, the USDA reported that a strain of avian flu — H5N1 2.3.4.4b — had infected herds of dairy cows in five states, and chicken producers across the country are also culling millions of birds in efforts to control outbreaks in poultry.

A person working on a dairy farm with infected cows in Texas soon tested positive for the avian flu, leading experts to suspect he contracted the virus from a cow.

This is the first time avian flu has been detected in US livestock and the first time a human has seemingly contracted the virus from a mammal (and not from exposure to an infected bird), but that doesn’t necessarily mean we’re on the brink of a new pandemic.

The chance of you getting sick from the milk of an infected cow is extremely low.

Even though these are the first reported cases of avian flu in cows, H5N1 has been detected in more than 30 mammal species previously, so the virus making the leap into one more isn’t entirely surprising.

The fact that these are dairy cows — and therefore in the human food chain — does make this more noteworthy than, say, when the virus was spotted in tigers for the first time, but the chance of you getting sick from the milk of an infected cow is extremely low, thanks to pasteurization.

Farmers are also being directed to destroy milk from any cows they know are infected.

It isn’t entirely clear how the virus is spreading in cattle — it could be spreading through the air, through contaminated milking equipment, or some other vector. While mammals usually contract H5N1 from a bird and then either recover or die without spreading the virus to other mammals, mammal-to-mammal transmission isn’t entirely unheard of.

In 2022 and 2023, the virus appeared to spread between farmed minks, and some people who’ve contracted the virus in the past had no known contact with infected birds before getting sick, suggesting that they might have gotten it from another person or mammal, too.

That makes the spread of the virus between cows rare, but not unprecedented, and thankfully, the virus isn’t making the animals too sick — they have mild fevers, decreased appetites, and decreased milk production, but recover fairly quickly.

The farmer who caught the virus from a cow, meanwhile, only had one symptom — conjunctivitis (pink eye) — and is now recovering after treatment with an antiviral medication.

The US has been studying H5N1 for years and has stockpiled avian flu vaccines.

While the CDC notes that the current risk to the public “remains low,” the more opportunities the avian flu virus has to spread, the more chances it gets to mutate into something that is dangerous.

Thankfully, the US has been studying H5N1 for years and has stockpiled avian flu vaccines and treatments just in case the virus becomes more contagious or starts to cause more severe infections. Other ways to protect humans and livestock from the virus are in the works, too.

Stopping human infections

The fact that we’ve already developed avian flu vaccines means that, if a threatening strain of bird flu emerges, we should be in a better place than we were at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when we didn’t have any coronavirus vaccines.

However, the vaccines we have for bird flu might not be as effective as they were when they were first developed.

By the time a targeted shot was designed and manufactured, the virus could be widespread.

Flu viruses mutate readily, and because a vaccine that works great against one strain might not be effective against another, developers of human flu vaccines tweak their shots every year to target the handful of strains they think will dominate the upcoming flu season.

Unfortunately, because it takes a long time to manufacture large quantities of flu vaccine using the traditional method — growing the virus in chicken eggs and then inactivating it — they need to pick a target 6-9 months in advance, and that long lead time can make it hard to choose the best one.

We could face this same problem with avian flu vaccines.

The strain that infected the Texas farmer was “closely related” to the ones used for existing avian flu shots, according to the CDC, but not an exact match. A strain that was able to spread from person to person could be significantly different, and by the time a targeted shot was designed and manufactured, the virus could be widespread.

Even if a potential epidemic strain wasn’t radically different, though, a bird flu outbreak could actually kill a lot of the chickens that we need to lay the eggs to make a vaccine — and the more the virus spreads, the more chances it has to mutate and dodge our immune defenses.

mRNA vaccines — the kind approved for COVID-19 — can be designed and manufactured more quickly than traditional flu shots, and they don’t require any birds or eggs, which could make them a better option in the event of a future avian flu outbreak.

Several vaccine makers are already developing the shots, too, including Moderna — in March 2023, it announced that it was working on an mRNA-based avian flu vaccine, which it said it planned to test in humans before mid-year (though there hasn’t been an update on the shot since).

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, meanwhile, published a paper in 2022 detailing a promising mRNA-based vaccine that targets 20 strains of flu, including H5N1, and in 2023, they shared a preprint of a study that found a version targeting H5N1 2.3.4.4b, specifically, was effective in animals.

More research is needed to get any mRNA shot for bird flu across the finish line, but developing them now — before a threatening strain is already spreading — means we have a better chance of having one ready if we need it.

Protecting poultry

Because the avian flu starts in birds, stopping them from getting infected in the first place could be an even better way to prevent a pandemic, not to mention save the lives of potentially millions of birds and protect the global supply of eggs and poultry.

Avian flu vaccines for birds could be one way to do that.

In 1994, Mexico became the first nation to vaccinate chickens against a strain of bird flu, and more than a dozen others have since followed suit, with China relying heavily on vaccination to protect its flocks.

US farmers have avoided avian flu vaccines for livestock due to issues with exporting poultry and eggs from vaccinated birds. Instead, as in many countries, they rely on culling to stop outbreaks — if one bird tests positive, the entire flock is killed.

That could change, though.

“Maybe it’s time to discuss vaccination.”

Monique Eloit

In April 2023, the USDA began trialing several vaccines to protect birds against H5N1 2.3.4.4b, and the following month, the World Organisation for Animal Health — an intergovernmental group focused on animal disease control — suggested that vaccines should be considered.

“Since almost every country that does international trade has now been infected, maybe it’s time to discuss vaccination, in addition to systematic culling which remains the main tool (to control the disease),” Monique Eloit, WOAH’s director general, told Reuters.

Vaccine development is slow going, though, with US Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack telling Congress in February 2024 that the USDA is “probably 18 months or so away” from identifying a vaccine that would be effective against the strain of avian flu that’s currently spreading.

Even if the USDA does develop an effective vaccine for this strain, it then needs to work out the logistics of manufacturing and distributing the shots — and then go through the process again for future strains.

“Gene-editing offers a promising route towards permanent disease resistance.”

Mike McGrew

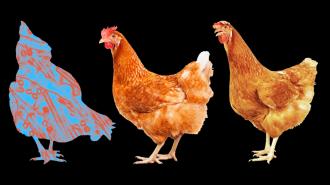

A more radical idea for protecting poultry from avian flu is taking shape in the UK, where scientists are trying to use CRISPR to genetically engineer chickens that cannot catch the flu at all.

In 2023, the team announced that editing one gene stopped chickens from producing a protein that the avian flu virus uses to replicate itself inside cells. When intentionally exposed to the virus, just one out of 10 gene-edited birds was infected, and that one didn’t spread the virus to any others.

The UK researchers suspect they’d need to make two more edits to the chickens to confer total immunity, and more research is needed to see how that might affect the health of the birds. If it proves safe and effective, though, the CRISPR approach could be a lasting solution to the bird flu problem in chickens.

“Gene-editing offers a promising route towards permanent disease resistance, which could be passed down through generations, protecting poultry and reducing the risks to humans and wild birds,” said Mike McGrew, the study’s principal investigator, in October 2023.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].