Using an AI model similar to the one powering internet darling ChatGPT, the California-based biotech Profluent has created novel antimicrobial proteins, and they’ve already proven capable of killing bacteria in the lab.

The successful proteins, published in Nature Biotechnology, were part of the first clutch of designs generated by Profluent’s AI platform, ProGen.

ProGen is a large language model (LLM), a form of deep learning AI that utilizes a universe’s worth of text as its training data, developing the ability to analyze and generate language — like ChatGPT, except in Progen’s case the language is that of proteins.

An AI model similar to ChatGPT has designed new proteins capable of killing E. coli bacteria in the lab.

“While companies are experimenting with exciting new biotechnology like CRISPR genome editing by repurposing what nature has given us, we’re doing something different,” Ali Madani, Profluent’s founder, said in a statement announcing the startups’ launch.

“We use AI and large language models like the ones which power ChatGPT to learn the fundamental language of biology, and design new proteins which have the potential to cure diseases.”

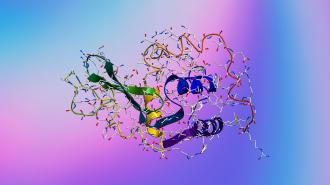

Talking protein: Proteins are bogglingly complex molecules, chains of amino acids strung together over millennia of evolution. The code for that chain is written in DNA, but proteins themselves work in three dimensions, twisting and curling like biological cursive.

One can think of a protein’s structure kind of like a language. It has a base of 20 different amino acids, which can be linked together in any order, and then fold up into the most complex origami imaginable — its grammar.

Researchers at Profluent aimed to create an AI model based on the language of proteins, which could be prompted to “write” new, never-before-seen proteins, with any desired shape or feature.

Rather than learning from the words of the internet, like ChatGPT, ProGen instead learned the language of proteins. The LLM was trained on 280 million protein sequences, the authors wrote, with guardrails built in to help it specify for certain protein properties.

The team then asked ProGen to generate sequences related to a group of antimicrobial proteins called lysozymes — small proteins credited as the first discovered antibiotics that attack the walls of bacteria and are naturally created by animals, ourselves included. They’re found in blood, tears, mucus, and hen eggs.

The large language model AI was trained on the “language” of proteins — 280 million different protein sequences.

Novel antimicrobial proteins: ProGen generated a million different artificial sequences, and researchers picked 100 of them to synthesize in the lab. Of those, 66 generated chemical reactions similar to the hen egg white lysozyme, which was used as a positive control, New Scientist reported.

The team then selected five of the novel antimicrobial proteins and tested them against E. coli. Two of the new proteins were capable of killing the bacteria.

X-ray imaging showed that, although these antimicrobial proteins’ amino acid sequences diverged more than 30% from any known natural proteins, they still folded into shapes nearly identical to their natural cousins.

“It was sort of an ‘it looks like a duck, it quacks like a duck’ situation and X-rays confirmed it also walked like a duck,” James Fraser, a professor of bioengineering at the University of California, San Francisco and member of the study group, told New Scientist.

While their antimicrobial proteins won’t be in the clinic soon, the study does show potential for using language AI models for “precise de novo design of proteins to solve problems in biology, medicine, and the environment,” the authors wrote.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at tips@freethink.com.