A surgical team has completed the first human ear reconstruction using a 3D-printed ear implant — molded out of the patient’s own cells.

The surgery is part of the first trial testing the technology on patients with microtia, a rare congenital deformity wherein the outer ear may be underdeveloped or missing.

Queens-based regenerative medicine company 3DBio Therapeutics developed the implant, called the AuriNovo.

The trial, which includes 11 patients, is ongoing and designed to test the ears’ safety and patients’ satisfaction with them.

“As a physician who has treated thousands of children with microtia from across the country and around the world, I am inspired by what this technology may mean for microtia patients and their families,” Arturo Bonilla, a pediatric ear surgeon at the Microtia-Congenital Ear Institute in San Antonio who led the surgical team, said in the company’s press release.

A surgical team has completed the first human ear reconstruction using a 3D-printed ear implant — made with the patient’s own cells.

3D-printing body parts: 3D printing has been used before to create other kinds of implants and prosthetics.

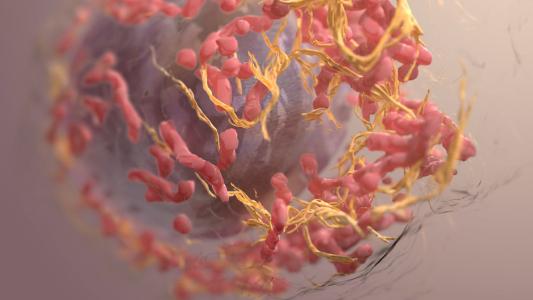

But by using “bioinks” made from biological material, 3D printing can create structures made of living tissue. Researchers have printed nose cartilage, bone, and mini-organs for drug development, but the AuriNovo transplant represents a large step for bioprinted therapeutics as a clinical field.

“It’s definitely a big deal,” Adam Feinberg, a professor of biomedical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, who was unaffiliated with the study, told the New York Times.

“It shows this technology is not an ‘if’ anymore, but a ‘when,’” said Feinberg, also a co-founder of 3D-printing regenerative medicine company FluidForm.

To protect its trade secrets, 3DBio has not revealed many details about their process, but the company says that data from their trial will be published in a medical journal when it is completed.

The surgery: The broad steps of the process were reported in the NYT.

First, Bonilla, the surgeon, took a half gram sample of cartilage from the microtia ear remnant of the patient, a 20-year-old woman from Mexico identified as Alexa.

He sent the sample and a 3D scan of Alexa’s other, healthy ear to 3DBio in Queens, where the cells responsible for forming cartilage were sifted out and cultured. The cultured cells were mixed into a cartilage-based bioink, which was then used to print an exact mirrored replica of her intact ear in under 10 minutes.

Bonilla then implanted the replica ear subcutaneously.

The future: The current treatment for microtia often involves removing enough cartilage from the patient’s ribs to shape into a new ear implant, but the new process is far less invasive.

“I’ve always felt the whole microtia world has been waiting for a technology where we wouldn’t have to go into the chest, and patients would heal from one day to the next,” Bonilla told the NYT.

3DBio founders Lawrence Bonassar and Dan Cohen see the surgery as the end result of almost two decades worth of academic groundwork — finally bridging the “valley of death” for new treatment ideas between the lab and the clinic.

“3DBio has successfully taken over where academia leaves off and has truly industrialized the technology,” Cohen told the Cornell Chronicle.

When a technical barrier is conquered, progress can be rapidly accelerated, Cohen said, citing aviation and computing as examples.

“Now that we believe we’ve cleared those fundamental hurdles, this technology platform could potentially make an impact in the lives of patients, and be the start of a new treatment paradigm.”

As Feinberg pointed out to the NYT, 3D-printed cartilage for an exterior structure is still a far cry from complex solid organs like livers, hearts, and lungs. But, he noted, the jump to other body parts is a lot more feasible when you’ve already got the ear.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].