“Diving with a rebreather is the second most lethal activity in the world per hour, after BASE jumping,” says Rachel Lance, a researcher at Duke, writing in Task & Purpose.

Hypoxia — lack of oxygen — is one of the biggest reasons why, sneaking up slowly on divers as they draw down to what may be their last breaths.

Now, Duke University researchers have developed a new method that will make diving with a rebreather safer.

The researchers discovered that devices that measure the amount of oxygen in your blood, when attached to the forehead and clipped to the nose, can provide rebreather divers with around half a minute’s warning that their oxygen levels are dipping dangerously low — leaving them at risk of blacking out underwater.

“The divers almost never know what hit them,” Lance wrote, “and the ocean rarely offers second chances.”

Rebreather diving is the second most lethal activity in the world per hour, and hypoxia — the lack of oxygen — is one of the main reasons why.

The risks are real: On May 5, 2009, Dewey Smith died during a rebreather dive.

Smith was about as experienced a diver as one could be; after a career with the Navy, he took his passion and skill to the civilian sector, working underwater with NOAA.

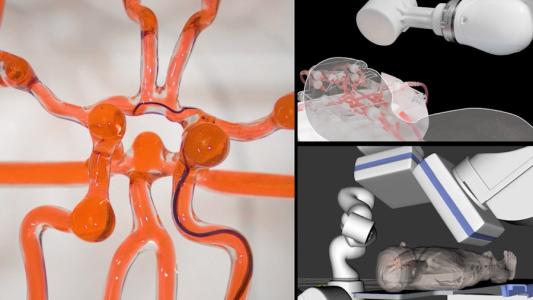

Rebreather systems are different from the scuba setups you’re picturing right now, with the billowing bubbles marking a diver’s every exhale. As the name suggests, rebreathers work by recycling the air a diver breathes, adjusting the CO2 and oxygen levels to ensure each breath is safe.

Part of that role includes replacing the oxygen that is lost as the diver breathes.

During Smith’s final dive, the violent vibrations caused by a nearby underwater jackhammer turned off the computer that was monitoring and controlling the amount of oxygen in Dewey’s air. He had no way of knowing that new oxygen was not being added.

“Dewey Smith was an extraordinarily experienced, skilled, and well-trained diver,” Lance wrote. “Still, on that warm summer day in the Florida Keys, he breathed in the last remaining molecules of oxygen available to him, lost consciousness, and died.”

“The divers almost never know what hit them, and the ocean rarely offers second chances.”

Rachel Lance

Although Lance didn’t know Dewey personally, the accident inspired her to develop a way to protect rebreather divers from hypoxia.

She turned to pulse oximeters, medical devices that use light beams to measure the oxygen saturation of the blood. You’ve probably seen them at hospitals or doctor’s offices, usually worn on the fingertip.

“We may finally have found a way to prevent a tragedy like Dewey Smith’s accident from happening,” Lance wrote, “albeit more than a decade too late.”

32 seconds between life and death: The Duke team’s work, published January 2022 in Annals of Biomedical Engineering, built on previous studies testing the use of pulse oximeters on a diver’s forehead, beneath their masks, on dry land.

When the results looked promising, Lance and colleagues continued their work, but this time they took it to the pool. Volunteers jumped into temperatures that varied from warm to breezy — with the fresh ice added in sometimes still floating top — to test if different conditions would interfere with the oximeters.

They found that the pulse oximeters provided a warning of oncoming hypoxia an average of 32 seconds in advance — long enough to switch to another air source or signal for help.

Each subject breathed from a rebreather that purposefully lacked oxygen and pedaled on an underwater bike.

The researchers found that the pulse oximeters provided a warning of oncoming hypoxia an average of 32 seconds in advance — although it varied from 17 to 58 seconds — long enough for a rebreather diver to switch to another air source or signal for help.

“The concept, if it can be built into something rugged, simple, convenient, clean, and robust enough for divers to actually want to use, then it just might save someone’s life,” Lance wrote.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].