Update, 9/9/21, 9:00 AM ET:

The Wall Street Journal reported on September 1 that the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) sent letters to McDonald’s franchisees this summer, asking questions about ice cream machines, including how often they, the franchisees, are allowed to work on them.

The letter explicitly notes that this “preliminary investigation” doesn’t mean the FTC has evidence of wrongdoing, and it’s not clear whether the Kytch’s lawsuit has any connection — Kytch and Taylor both deny being contacted by the agency.

The FTC voted in July to start developing policies that supported consumers’ right to repair their own possessions. It also said it would be investigating companies with potentially unlawful repair restrictions.

Now, it seems the right to repair McDonald’s ice cream machines is on the agency’s radar — even if McDonald’s seems to be in denial.

“Nothing is more important to us than delivering on our high standards for food quality and safety, which is why we work with fully vetted partners that can reliably provide safe solutions at scale,” it said in a statement. “McDonald’s has no reason to believe we are the focus of an FTC investigation.”

A judge just issued a victory to a startup that makes it easier for fast food franchise owners to repair McDonald’s ice cream machines — but the soft-serve saga isn’t over yet.

The background

More than 90% of McDonald’s U.S. restaurants feature an $18,000 ice cream machine made by food-equipment manufacturer Taylor (others have a machine made by a company in Italy, but the long wait for parts is generally a deterrent).

These machines are advanced, as far as ice cream-making devices go. Not only do they have the unique ability to produce both soft serve and milkshakes, they need to be disassembled and cleaned just once every two weeks instead of daily, like most other machines.

McDonald’s ice cream machines are also temperamental — they break so often that someone built a website just to track which ones are down at a given time (11% are out of commission, at the time of writing). Heck, even McDonald’s has joked about the machines breaking on its official Twitter account.

“It’s a huge money maker to have a customer that’s unable to make fundamental changes to their own equipment.”

Jeremy O’Sullivan

About 85% of McDonald’s U.S. restaurants are franchises, which means they’re independently owned and operated — someone is paying McDonald’s a fee to sell its products under its brand name.

When one of McDonald’s ice cream machines breaks, these franchise owners have to contact a Taylor distributor to send out a certified technician. That technician then enters a not-so-secret code that unlocks a menu, revealing diagnostic information about the machine and the meaning of any error codes.

Because McDonald’s ice cream machines break so regularly, franchisees often spend thousands of dollars on service contracts with Taylor distributors every year — and Taylor gets a cut of those profits.

“It’s a huge money maker to have a customer that’s purposefully, intentionally blind and unable to make very fundamental changes to their own equipment,” Jeremy O’Sullivan, co-founder of foodtech startup Kytch, told Wired in April.

The Kytch solution

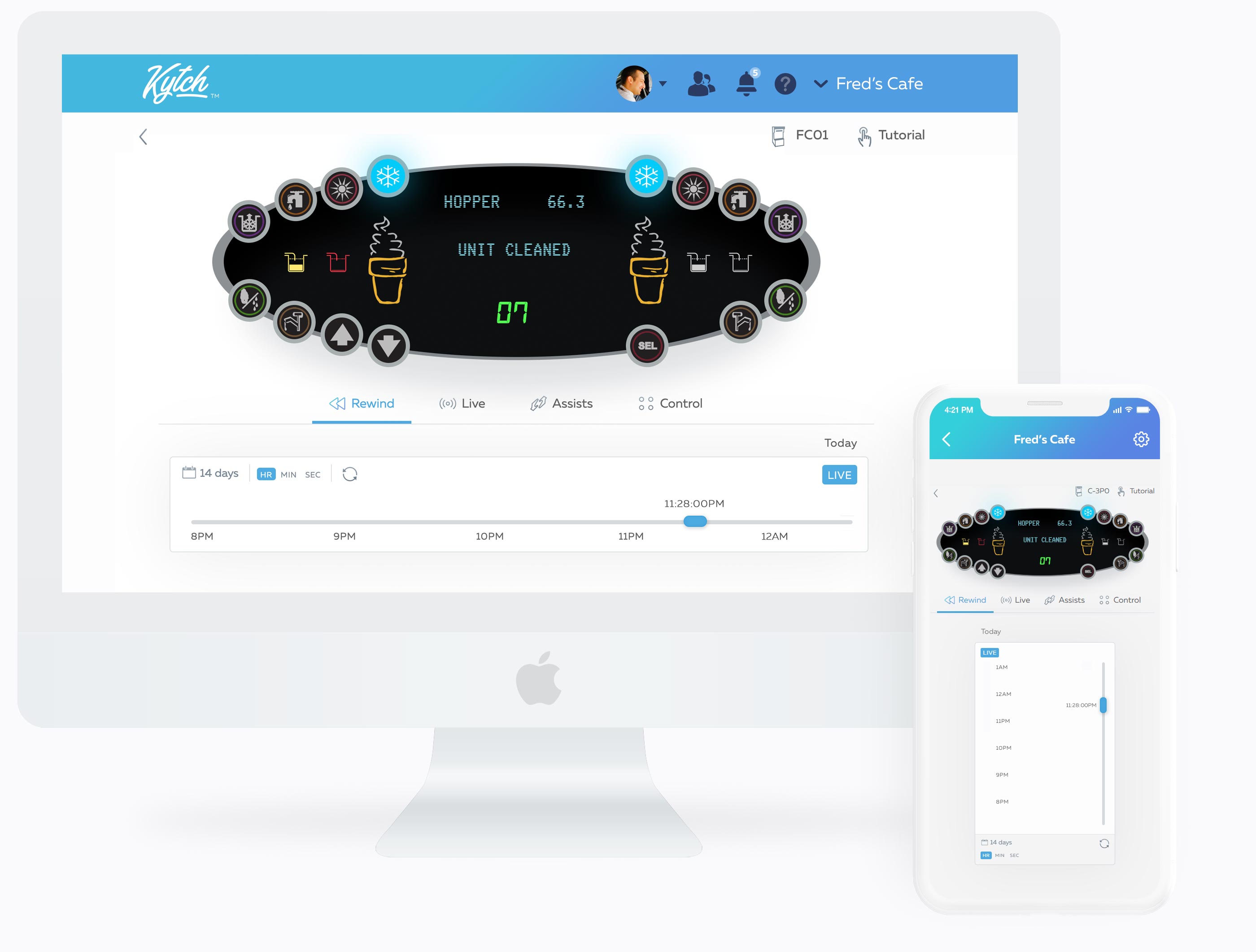

In May 2019, Kytch began selling a small gadget that hacks into this previously inaccessible data — owners just have to install it on their Taylor ice cream machine (a reportedly simple process that requires 20 minutes and a screwdriver) and connect it to WiFi.

The device (called a Kytch) will then monitor the machine 24/7, providing real-time information via the startup’s website. It even offers troubleshooting advice when something goes wrong, giving franchisees an opportunity to repair the machines themselves.

“It’s almost scary to think about having … soft-serve units without these devices.”

CJ Timoney

Kytch requires a $20 monthly subscription and a $250 activation fee — and soon after its launch, fast food franchise owners were raving about the gadget.

“After not having it, it’s almost scary to think about having shake machines without these or soft-serve units without these devices,” CJ Timoney, who owns eight Burger King franchises, told Business Insider in February 2020.

The pushback

Everything was going great for Kytch until November 2020 when McDonald’s sent all of its franchisees an email warning them that installing a Kytch voided the warranty on their ice cream machines.

The email also claimed, according to Wired’s detailed report, that a Kytch “creates a potential very serious safety risk for the crew or technician attempting to clean or repair the machine” and could cause “serious human injury.”

“Kytch has only made the shake machine better, more reliable, with less downtime.”

Jeremy O’Sullivan

The final line of the email was written in italics and bold: “McDonald’s strongly recommends that you remove the Kytch device from all machines and discontinue use.”

Another email from McDonald’s arrived the next day, announcing the “Taylor Shake Sundae Connectivity” — a device that replicates many of Kytch’s features.

The lawsuit

Over the next few months, hundreds of franchisees canceled their Kytch subscription plans, and it became impossible for the company to find new customers.

In May, Kytch filed a lawsuit against Taylor, alleging that the company obtained one of its devices illegally — franchisees are forbidden from sharing them with third parties — and then told McDonald’s they were dangerous despite a lack of evidence.

“This false claim has been extremely damaging to our company and our customers,” O’Sullivan had told Business Insider prior to filing the lawsuit. “Kytch has only made the shake machine better, more reliable, with less downtime.”

“The manufacturers like to pretend they have the best answers for fixing equipment. That’s nonsense.”

Nathan Proctor

On July 30, a judge issued a temporary restraining order against Taylor and told it to give back any Kytch devices it had obtained. That fulfills one of Kytch’s requests in the lawsuit — the other is for Taylor to pay it a to-be-determined amount of money in damages.

“These guys did a really effective job at frightening off all of our customers and investors so we’re hoping the public will support our case in the name of justice, right to repair, and humanity,” O’Sullivan told Motherboard.

“We still have some diehard customers sticking with us,” he continued, “though few in comparison to what we once had before McDonald’s and Taylor called our product dangerous.”

The bigger picture

The saga of McDonald’s ice cream machines is just one example of the broader right-to-repair movement, which argues that consumers should have the ability to repair purchases themselves, or at least decide who to turn to for help.

This is standard for many types of purchases — when you own a car, there’s nothing to stop you from fixing a brake problem yourself or taking the vehicle to your favorite auto mechanic — but many companies keep the info and parts needed for repairs to themselves.

Nobody can force them to share that information, but many companies go further, with terms of service or warranty restrictions that require customers to use their proprietary repair service. Even if you have the know-how and ability to repair it, you might not risk it.

“The manufacturers like to pretend they have the best answers, if not the only answer, for fixing equipment,” Nathan Proctor, Director of the U.S. PIRG’s Campaign for the Right to Repair, told Freethink. “That’s nonsense.”

Giving people the ability to repair their own property — like Kytch does for owners of McDonald’s ice cream machines — can save them money, but that’s just one benefit, according to Proctor.

“Sometimes it means innovations that improve the product, like in the case of Kytch,” he explained. “We can’t let manufacturers squash all that innovation because they don’t feel like competing.”

For now, all Kytch can do is hope a judge agrees with the allegations in its lawsuit.

“Kytch is just a small piece of the broader right-to-repair movement,” Kytch co-founder Melissa Nelson told Motherboard. “But our case makes clear that it’s past time to end shady business practices that create hundreds of millions of dollars of unnecessary repair fees from ‘certified’ technicians.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].