This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

Earth is only so big and the resources on it are finite, so, if humanity grows beyond what this planet can support, we may have to find an off-world home. If the most dire climate change predictions come true, or if there’s an asteroid or comet we can’t deflect, or if a supervolcano erupts, we may need one.

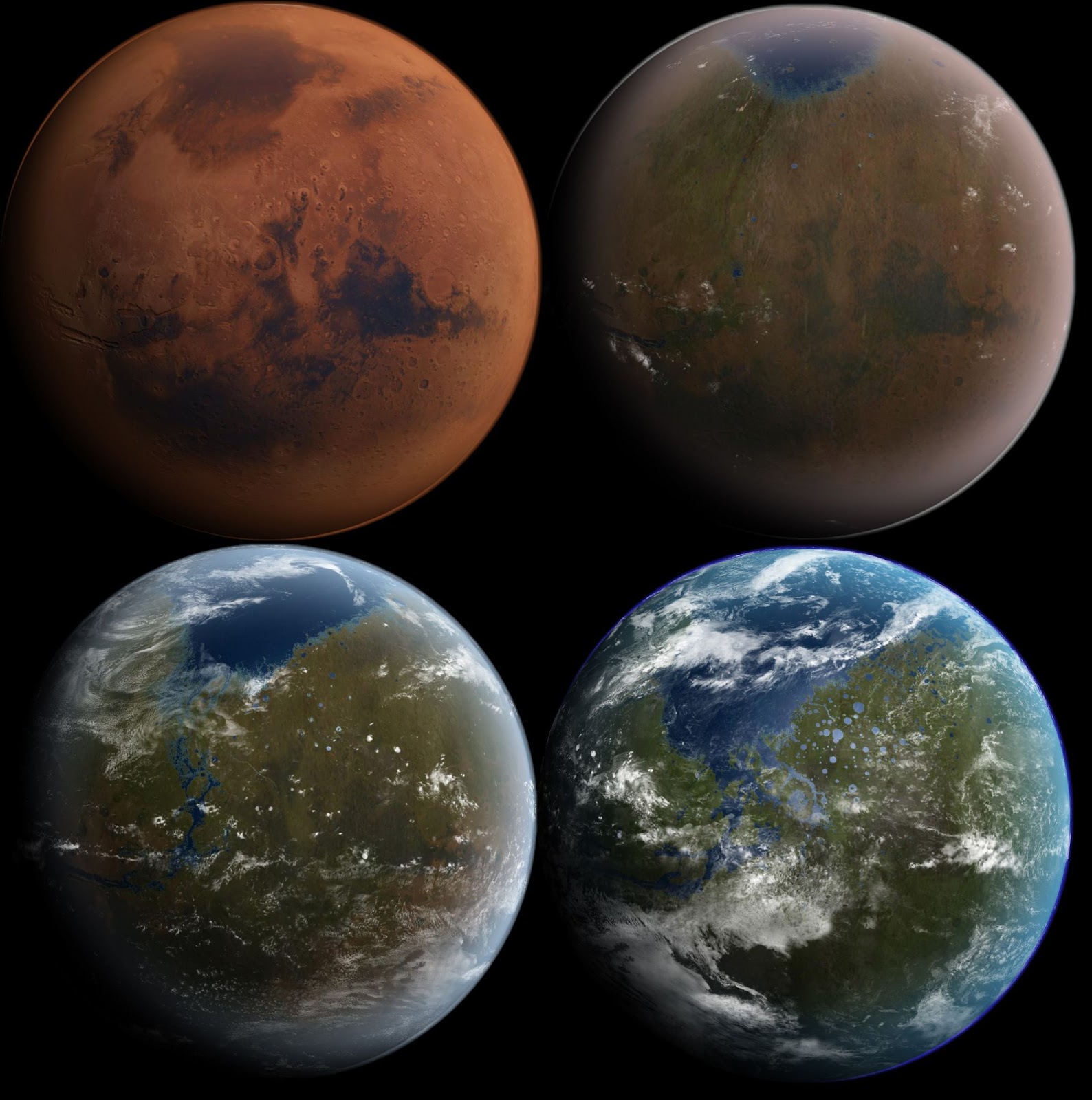

Currently, there isn’t anywhere in the solar system besides Earth where large numbers of people could live for any length of time — but some people believe we might be able to make Mars habitable through terraforming.

Terraforming Mars

Terraforming is the hypothetical process of altering a planet or moon to be Earth-like enough to support human life, outside of an artificial base — at its barest level, that means a breathable atmosphere, liquid water, and tolerable temperatures. Not having so much cosmic radiation that it causes cancer would be helpful, too.

Mars is generally considered the most viable candidate for terraforming, due to its relative closeness to Earth, both in terms of distance and other characteristics. (Venus is closer in size to Earth, but it is incredibly hot, with temperatures at night around 800 F, and has a crushing atmospheric pressure over 90 times greater than Earth’s.)

Mars’ orbit is relatively close to Earth, and it is a terrestrial planet with water (at least, ice) on its surface. And in the distant past, it’s possible Mars once had a lot of liquid water on its surface and a thicker, warmer atmosphere.

To make Mars habitable for humans today, though, we’d need to change a lot about the planet.

Terraforming is the hypothetical process of making another place in space “Earth-like” enough to support human life.

One of the biggest problems with the Red Planet is its thin atmosphere. Earth’s thick atmosphere helps protect us from solar radiation and provides the oxygen we need to survive. While scientists believe Mars once had a thick atmosphere, today it’s less than 1% as dense as Earth’s, and oxygen makes up less than 1% of it, compared to 21% on Earth.

This thin atmosphere allows heat to readily escape Mars’ surface, leading to wild temperature fluctuations on a planet where the average temperature is already a not-so-hospitable -85°F.

“There might be a 15-20 degree [Fahrenheit] temperature change between where your feet are and where your head is if you were standing on Mars,” said Matthew Shindell, curator of planetary science and exploration at the National Air and Space Museum.

We’d need to change a lot about Mars to make it habitable for people.

Another key difference between Earth and Mars is that our planet is surrounded by magnetic fields. These create a “magnetosphere” that protects us from cosmic radiation and the solar wind that could otherwise strip away our atmosphere. Mars lost its own magnetosphere about 4 billion years ago, so even if we could build Mars a new atmosphere, it wouldn’t last long without a magnetosphere, too.

So, how might we go about overcoming these issues by terraforming Mars?

Building a magnetosphere

Mars, like Earth, has five Lagrange Points, places in space where the gravitational pull of the planet and the sun create a sort of equilibrium that causes smaller objects to orbit the sun along with the planet.

In 2017, James Green, then-director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, proposed placing a device that creates a magnetic field at the Lagrange Point between Mars and the sun. This “magnetic shield” would function effectively as an artificial magnetosphere, preventing atmosphere-stripping solar wind from reaching the Red Planet.

“Stop the stripping, and the [atmospheric] pressure is going to increase,” Green told the New York Times in 2022. “Mars is going to start terraforming itself.”

“That’s what we want: the planet to participate in this any way it can,” he continued. “When the pressure goes up, the temperature goes up.”

Release the gasses

As we’ve (unfortunately) learned from Earth, increasing the amount of greenhouse gasses in a planet’s atmosphere is another way to thicken it and heat up the surface, and there are several proposed ways we could do the same for Mars.

Casey Handmer, a former software system architect at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, has suggested we send a fleet of solar sails — devices propelled by sunlight — to Mars. They could then reflect extra sunlight onto the planet’s frozen CO2, causing it to sublimate and thicken the atmosphere.

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk has famously suggested we could release CO2 and water vapor — another greenhouse gas — by dropping nuclear bombs on the Martian polar ice caps. That plan could work, in theory, but it’s also been criticized for both the large number of nukes required (~10,000) and the possibility that it could backfire, creating a nuclear winter on Mars.

Some experts say there isn’t enough frozen CO2 on Mars to significantly warm the planet, so other proposals suggest building greenhouse gas-emitting factories on Mars or redirecting ammonia-rich asteroids so that they slam into the planet and release the gas into its atmosphere.

“Nuke Mars!”

Elon Musk

Make a lake

Not every terraforming proposal aims to rapidly make all of Mars habitable for people — some suggest we start smaller, reshaping just part of the Red Planet. One of the most radical is the Mars Terraformer Transfer (MATT) concept.

Unveiled in 2017 by a research group called the Lake Matthew Team, it also proposes redirecting an asteroid so that it slams into the Martian surface. In this instance, the purpose is to create a crater that, warmed by the asteroid impact, would melt local ice and create a lake of liquid water. This lake could then help support a Mars settlement.

“Whereas prior designs of habitation structures (habs) were limited to thousands of cubic meters, MATT habs can scale to millions of cubic meters — stadium scale, or greater,” wrote the Lake Matthew Team.

Beyond the Red Planet

None of these ideas for terraforming Mars have gone anywhere beyond the proposal stage, and it may ultimately be impossible to turn the Red Planet into Earth 2.0 — but Mars isn’t our only option.

Some scientists have suggested we might have better luck attempting to terraform Venus, despite its extremely inhospitable climate today. Venus is generally closer to Earth than Mars, and its gravity is 90% of Earth’s, meaning health issues associated with lower gravity likely wouldn’t be as pronounced (Mars’ gravity is only about one-third of Earth’s).

Venus is way too hot for people, but we might be able to cool it with a solar shade, and unlike the Red Planet, it already has a dense atmosphere. Like Mars, we’d need to boost its oxygen content, but the density problem on Venus is actually the opposite of Mars: we’d need to drastically lower its atmospheric pressure.

Terraforming the moon is another possibility that some have floated. On the plus side, it’s way closer to Earth than Mars or Venus, which would help with communication and supply deliveries, and while it doesn’t have a magnetic field, it’s close enough to Earth’s magnetosphere to glean some solar wind protection from it.

Lunar regolith, meanwhile, is more similar to Earth’s soil than the dust on Mars’ surface, which could make agriculture easier. But the moon has essentially no atmosphere, and it would be difficult to sustain one even if it could be generated.

The big picture

Ultimately, attempting to terraform Mars, the moon, or some other place in space would be a huge undertaking that would likely cost a vast amount of money, take a really long time, and potentially not even pay off.

If Earth ever became uninhabitable, though, we may be left with no option but to give it a shot, so studying it now may be worthwhile — and if we were somehow able to create a new Earth, we’d be wise to treat it with more care than our current one.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].