This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Saturday morning by subscribing here.

It’s 2035. Global electricity demand has skyrocketed, driven in large part by the data centers that support our digital world. Rather than worsening climate change, though, these power-hungry facilities are a major reason 100% of our electricity is now generated by clean energy.

Data centers

Data centers are facilities that house the computing hardware used to process and store data. While some businesses maintain their own data centers on site, many others rely on ones owned and operated by someone else.

As our digital world continues to grow, demand for data centers — and clean electricity to operate them — is also increasing. To find out how we’ll be able to keep up, let’s look at the history of data centers, the challenges facing them, and ideas for overcoming those issues — on land, at sea, and in space.

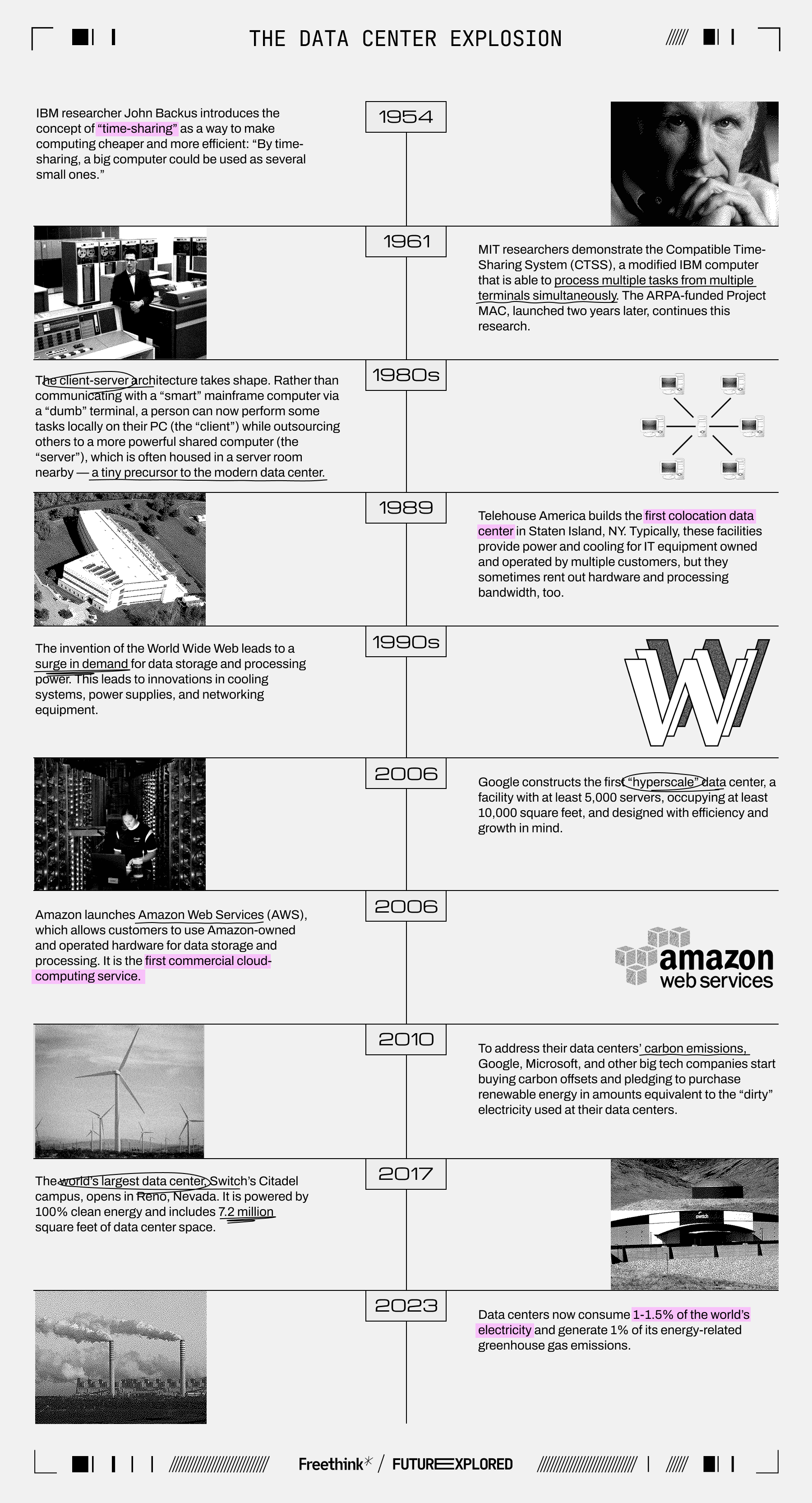

Where we’ve been

Where we’re going (maybe)

The need for more data centers with more equipment in them is skyrocketing due to video streaming, more remote work, businesses shifting to cloud computing, and, increasingly, the development of power-hungry AIs, which are projected to increase data center power demand by 160% over the next five years. By 2030, data centers will be consuming 8% of all US electricity.

To keep up with this demand, the number of hyperscale data centers has doubled in the past four years, and Bill Vass, VP of engineering at AWS, told attendees at the 2024 CERAWeek energy conference that a new data center of any size is now opening somewhere in the world every three days.

The power needs of these new data centers can be truly gigantic. Microsoft and OpenAI’s planned “Stargate” data center is estimated to cost $100 billion and will consume up to 5 gigawatts of electricity — more than the capacity of the largest nuclear plant in the US today. In northern Virginia, the power utility reports that planned data centers are asking for the equivalent of several nuclear reactors’ worth of new power.

We’re going to need ever more data center capacity, and because it takes so much energy to run and cool their equipment, they need to be built somewhere with a sufficient supply of reliable, affordable, and — ideally — clean energy.

“Trying to find qualified land sites that have sufficient power to stand up these facilities — you need 10 times what I built in 2006,” Jim Coakley, an owner and manager of high-security, high-density data centers, told the New York Times. “They are essentially inhaling massive amounts of energy.”

In the US, in particular, these demands are running up against an electricity sector that has hardly grown at all for 20 years. Huge numbers of proposed power plants are stuck in queues while they wait for permission to connect to the grid, while issues with permitting and transmission lines are further slowing down growth.

This situation is forcing data center developers to start thinking creatively for places to build their data centers and ways to power them. Here are a few ways tomorrow’s data centers could be made cleaner and more reliable while delivering the computing power we need to drive the tech of the future.

Testing the water

If you’ve ever tried to work with a laptop actually on your lap, you know that computers get hot, and preventing equipment from overheating is a major concern at data centers — it can not only disrupt service and damage equipment, but also lead to fires that injure workers.

Currently, up to 40% of the energy used at a data center can go toward its cooling systems, and with global warming increasing temperatures, cooling costs could soar even higher in the future, so data center developers are on the hunt for more efficient ways to keep temperatures low.

That search is leading some to the ocean floor.

In 2018, Microsoft sank a 40-foot-long data center module equipped with 864 servers onto the floor of the North Sea off the coast of Scotland. It then connected the module to the local grid, which is powered by 100% clean energy.

The goal was to see if the naturally low temperatures 117 feet underwater could reduce cooling costs, so Microsoft put the servers to work on internal projects before retrieving the entire data center in 2020.

Not only did the underwater data center prove to be more stable than a comparison group of servers on land, it also achieved an impressive power usage effectiveness (PUE) score — the standard metric used to measure data center efficiency — of 1.07. An ideal score is 1.0, and the average data center has a score of around 1.55.

While Microsoft hasn’t announced plans to build any more underwater data centers, it also hasn’t ruled it out in the future.

“While we don’t currently have data centers in the water, we will continue to use Project Natick as a research platform to explore, test, and validate new concepts around data center reliability and sustainability, for example with liquid immersion,” a Microsoft spokesperson said in a statement.

In 2021, the company open-sourced many of its patents from Project Natick, making it easier for others to pursue the concept. The same year, Chinese tech firm Highlander teamed up with government officials to begin building an underwater data center off the coast of Hainan Island, China.

Details are scarce, but what we do know is that it will feature 100 data center modules, each weighing 1,433 tons. Collectively, they’ll have the processing power of 60,000 traditional computers.

Construction of the underwater data center is expected to wrap in 2025, and project officials expect it to operate for 25 years. They also estimate it’ll be 40-60% more power efficient than an on-shore center. If successful, it could inspire others to take advantage of the benefits of building centers below water, which extend beyond efficient cooling.

“The underwater data center makes full use of the underwater space, which can not only save the occupation of land resources, but also be away from the area of human activities, providing a stable environment for server work,” Xie Qian, a senior engineer at the CTTL Terminal labs of the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, told China Daily.

Data — in spaaace!

Rather than building data centers on land — be it above or below sea level — some think we should be putting them in space, where solar energy is plentiful and low temperatures could be coupled with “innovative thermal dissipation” to radiate heat away from the servers.

“The idea for space-based data centers is not new, but due to the recent evolution of space access — with SpaceX, for instance — and also with the improvement of the digital sector, I would say it is now more realistic to consider a data center in space,” Damien Dumestier, a system architect at space manufacturer Thales Alenia Space, told Freethink.

To explore the potential for space-based data centers, the European Commission contracted Thales to lead the ASCEND (Advanced Space Cloud for European Net zero emission and Data sovereignty) study in 2022.

Thales then teamed up with partners in the aerospace, IT, and cloud computing industries to determine whether space-based data centers were technically feasible and, if so, if they would be better for the environment than terrestrial ones.

“It is something that we can do — maybe not tomorrow, but in a few years, it is possible to do it.”

Damien Dumestier

In 2024, Thales announced the results of the study: yes, they believe we can put some data centers in space, but for that to significantly reduce the environmental impact of the facilities, we’re going to need a more eco-friendly rocket.

“The main advantage regarding the environmental impact is that, as we will remove some electricity or energy consumption from Earth, we will avoid the emissions which are linked to this energy and to the production of this energy,” said Dumestier.

Because today’s rockets are not particularly eco-friendly, some of those benefits would be offset when we launched the data centers into space. If we can build a rocket that produces 10 times fewer emissions, though, the facilities could become a significant net positive for the environment, according to Thales’ research.

“It is not something that is unfeasible,” Dumestier told Freethink. “It is something that we can do — maybe not tomorrow, but in a few years, it is possible to do it.”

Thales is now putting together a roadmap for further study. Its goal is to secure funding to deploy 13 space data center “building blocks” in 2036. Collectively, these would have a capacity of 10 megawatts — enough for commercialization.

Although orders of magnitude smaller than many ground-based data centers, that system would still require a solar array five times larger than the one powering the International Space Station, so figuring out how to make it and the data center itself as light as possible will be an important part of making the launch ultra-efficient.

Protecting the equipment from space radiation and ensuring we can transmit data between it and Earth at high enough speeds are other considerations, but Thales is hopeful it will be ready to significantly scale up a space-based data center by mid-century.

“The final objective is to deploy around 1 gigawatt by 2050,” said Dumestier. “It is quite big, but the reason behind that is that we want to have a significant impact on carbon reduction. So the more that will be deployed, the more we have the impact.”

On dry land

While underwater and space-based facilities have the potential to host data centers, most developers are looking for down-to-earth solutions involving traditional land-based centers, the kind they already know how to build and deploy at the massive scales we need.

This means adopting more efficient hardware and cooling systems and powering the tech with solar and wind. It also means looking into off-grid solar and battery solutions and pushing to build more clean, reliable alternatives to solar and wind farms, which are becoming more challenging to build.

Google, for example, teamed up with Fervo Energy in 2021 to develop a next-generation geothermal power project. By 2023, that project was supplying clean energy to the local grid that powers Google’s data centers in Nevada.

Many big tech companies are also expressing interest in nuclear as a steady source of clean power. Amazon recently bought a nuclear-powered data center in Pennsylvania, which can tap into between 20-40% of the nearby nuclear power plant’s 2.5 gigawatt capacity.

Microsoft, meanwhile, has been working with Terra Praxis, a nonprofit focused on decarbonization, since 2022 to try to get coal-fired power plants converted into nuclear power facilities. As part of this, it is actually training an AI to help write the lengthy documents needed to secure approval for the new kinds of nuclear reactors that they’d like to help power their AI data centers.

“Microsoft wants to use our influence and purchasing power to create lasting positive impact for all electricity consumers.”

Adrian Anderson

Microsoft founder Bill Gates has also been independently backing nuclear startup TerraPower, which is pursuing new reactor designs and began construction of its first reactor at a decommissioned coal plant in Wyoming this year.

Microsoft and Google have also teamed up with steel producer Nucor Corporation to pool their demand for clean energy to help accelerate the commercialization of advanced nuclear, hydrogen, and geothermal systems.

The hope is that having multiple large customers lined up will help the developers of these systems secure the financing needed to get their projects deployed — increasing the supply of clean energy available to everyone, not just the companies processing and storing our data.

“Microsoft wants to use our influence and purchasing power to create lasting positive impact for all electricity consumers,” Adrian Anderson, general manager of Renewables, Carbon-Free Energy, and Carbon Dioxide Removal at Microsoft, told Freethink. “Collaborating with renewable energy providers drives the innovative development of more diverse energy grids globally.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].