By now, we are well into summer, and first-time gardeners have realized that growing plants is hard work. But growing a coral garden outside of the natural environment, even harder. It’s never been done before — until now.

Researchers have finally figured out how to keep sea anemone and coral cells alive in the lab. New research using the tiny sea creatures could be unlocked in fields from evolutionary biology to human health.

“We can also not grow coral cells and use them in experiments that will help improve our understanding of their health in a very targeted way.”

Nikki Traylor-Knowles

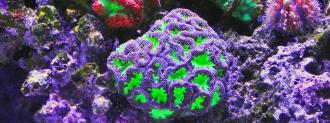

What they did: University of Miami cell biologist Nikki Traylor-Knowles and her team cultivated the starlet sea anemone (Nematostella vectensis) and cauliflower coral (Pocillopora damicornis) — the first coral garden in a laboratory setting.

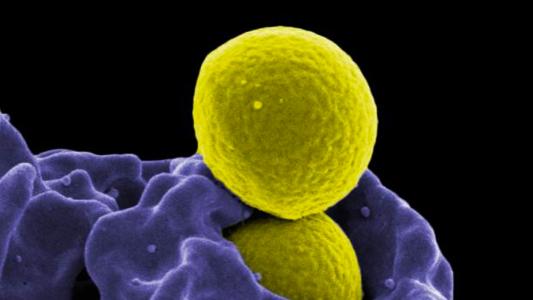

These two sea animals happen to be rising stars when it comes to model research organisms for cell and molecular biology. But keeping them alive in the laboratory coral garden was practically impossible. Even if researchers could successfully move them from the ocean to the lab without damage, they would die shortly after because their complex microbiome (a community of symbiotic bacteria) would grow unchecked and take over the cell culture.

But the UM team found an antidote.

After testing 175 cell cultures, the team found that antibiotics could help the cells survive for nearly two weeks. Their discovery was published in Scientific Reports.

“This is a real breakthrough,” said Traylor-Knowles in a statement. “We showed that if you treat the animals beforehand and prime their tissues, you will get a longer and more robust culture to study the cell biology of these organisms.”

Why this matters: This research won’t help your average aquarium lover — the coral cells only survived for about 12 days, so they’ll still have to rely on plastic coral gardens. But there’s big scientific potential here.

Researchers are becoming more interested in cnidarians — a broad group of marine animals with over 9,000 species, including that include corals, jellyfish, sea anemones, and even the Portuguese man o’ war — because they could be significant research subjects. Their unique characteristics of radial symmetry, a two-dermal cell layer, and a stinging cell known as a nematocyte could reveal new features of animal development.

Previously, researchers had to study corals while alive in the ocean or dead in a laboratory. This work could open up new doors for studying live corals in the convenience and flexibility of a lab, hopefully unlocking new insights that could be used to revitalize or protect dying coral reefs.

“We can also now grow coral cells and use them in experiments that will help improve our understanding of their health in a very targeted way,” said Traylor-Knowles.

Biologist Juris Grasis of the University of California, who was not involved with the study, calls it groundbreaking. He told Scientific American he was “jealous as hell” by the results. He says the next question is: “How do we translate this back into the field and make corals healthy again?”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].