This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Saturday morning by subscribing above.

It’s 2026. You check your smartphone and see a notification from your AI fitness coach. Based on data collected from your wearable fitness tracker, it has personalized recommendations on what you should do and eat today—taking the guesswork out of meeting your health goals.

Health wearables

Bryan Johnson is on a mission to live forever, and his chief weapon in the battle against the Grim Reaper is data.

“I am the most measured person in human history,” says Johnson, who bases his (hopefully) death-defying diet, exercise, and lifestyle decisions on the results of regular medical tests and data from a bevy of gadgets, including his WHOOP fitness tracker.

“Wearing WHOOP gives me a tremendous amount of insight into my overall wellness, whether it’s my sleep, my HRV [heart rate variability], my performance in my cardiovascular endeavors,” Johnson told Will Ahmed, WHOOP’s founder and CEO, in 2021.

Johnson spends $2 million annually on his anti-aging regimen, but people far less hardcore about their health are also drawn to health wearables like WHOOP—in 2023, nearly one-third of American adults surveyed said they used one of the devices, and adoption is trending up.

To better understand these increasingly ubiquitous devices, this week’s Future Explored is taking a look back at the history of wearable fitness trackers, current trends, and what the tech could mean for the future of health.

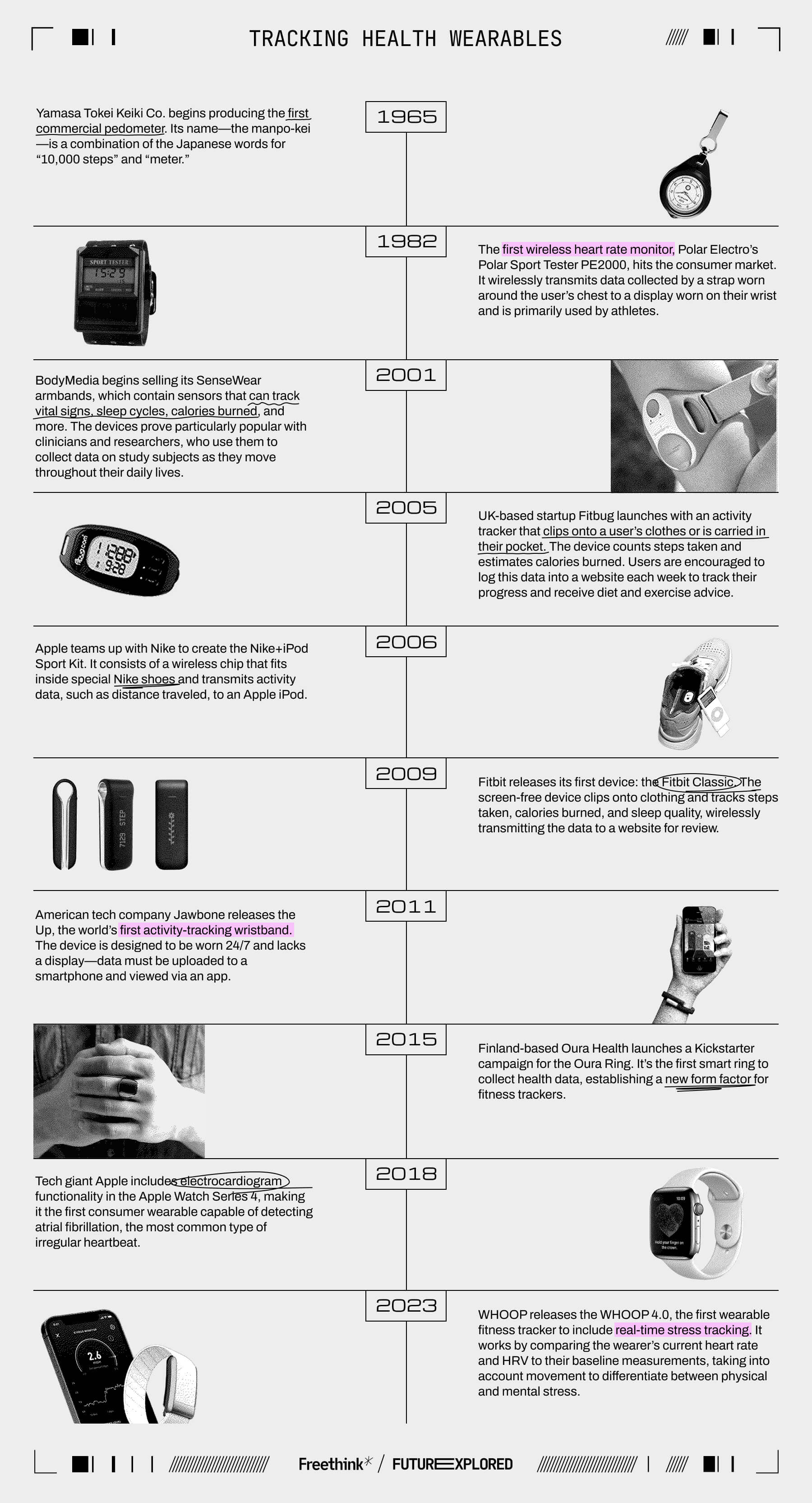

Where we’ve been

Where we’re going (maybe)

In the 60 years since the manpo-kei first inspired people to strive for 10,000 steps daily, wearables have gone from bulky, single-function gadgets to compact devices capable of revealing numerous insights into our health far more cheaply and conveniently than was previously possible.

So, what’s next?

Better batteries

Wearables aren’t worth the silicon their sensors are printed on if they just collect dust in a drawer, and there are a few ways developers are trying to encourage people to not only buy the devices, but actually use them consistently (making it more likely they’ll want to buy a new one when it’s released).

One is by improving their battery life.

“Powering wearable sensors is an issue that is not talked about enough.”

Amay Bandodkar

A 2016 survey of former wearable users found that the hassle of charging was a common reason people stopped using the devices—they grew tired of having to regularly remove their wearable and frustrated by lithium-ion batteries that held less and less charge over time.

“Powering wearable sensors is an issue that is not talked about enough,” Amay Bandodkar, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at North Carolina State University, tells Freethink.

Tech developers are hopeful that solid-state batteries could help solve this problem.

Because solid-state batteries charge more quickly and have a greater energy density than lithium-ion ones, they’d presumably lead to less wearable “downtime”—users wouldn’t need to remove their devices for charging as frequently, and when they did, they’d be able to top them off faster.

In 2024, TDK (Apple’s battery supplier) and Samsung separately announced they were developing these batteries for wearables, with the latter saying it expected to have them ready for the Galaxy Ring and Galaxy Watch as soon as 2026.

Solid-state batteries aren’t the only potential solution to wearables’ power problem.

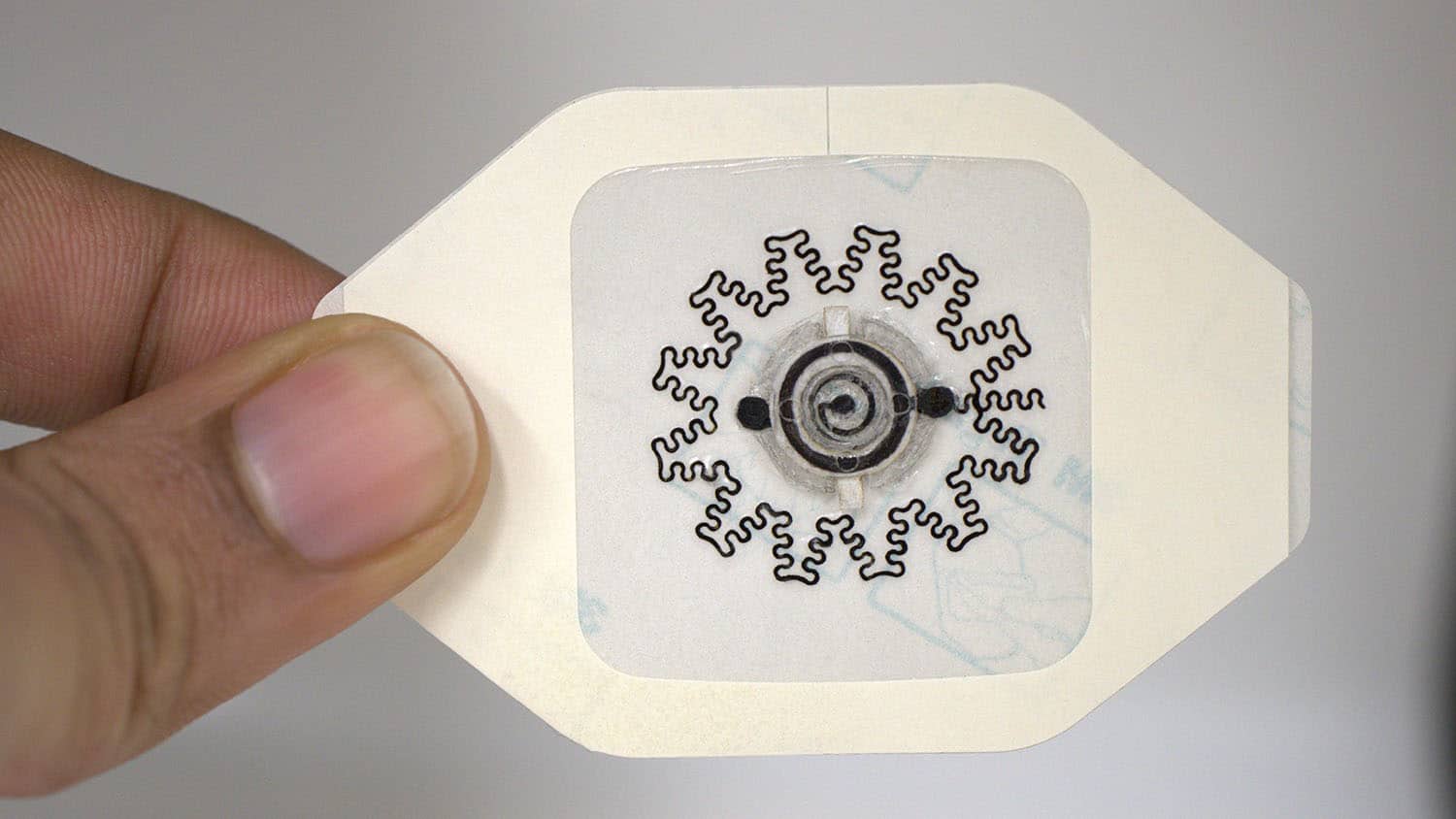

In 2020, Bandodkar and his collaborators demonstrated how a lightweight battery activated by sweat could be used to power an ultra-thin, stick-on sensor that monitors heart rate, sweat chloride, and sweat pH.

Queensland University of Technology researchers, meanwhile, have developed a cost-effective technique for making flexible films that can convert body heat into power for wearables, and a team at the University of Surrey has developed flexible “nanogenerators” that convert movement into electricity—the idea behind that tech is that you could go for a run in the morning and power your fitness tracker for the rest of the day.

Alternative batteries like these are already starting to make their way out of the lab—in 2023, healthtech company Baracoda began selling the Bheart, a wearable that uses ambient light and the user’s body heat to power its sensors—and even if they can’t provide all the power a wearable needed, they could extend battery life and make the devices more convenient.

Tracking everything

Because solid-state batteries or wafer-thin ones like what Bandodkar is developing are more compact than lithium-ion batteries, they could help create more variety in the wearable market—we could see devices that are worn in more places on the body and ones with capabilities beyond those of today’s wearables.

“While the products currently available on the market mostly track one’s vitals and are more geared towards general fitness monitoring, I believe that in the future there will be new types of wearables that can also monitor other important biomarkers and capture medically relevant data for accurate clinical decision making for patients,” says Bandodkar.

These could include everything from smart contacts lenses that monitor for signs of diabetes, mouthguards that analyze saliva for chronic stress indicators, and t-shirts with built-in sensors that can tell from your sweat when heat stroke is imminent.

We could even start to see wearables that treat health issues, rather than just track them. An example of this is the water-powered “smart bandage” Bandodkar’s team developed with support from the U.S.’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

“Our goal was to develop a robust bandage that is low-cost, easy to use, but at the same time, effective in treating wounds,” he tells Freethink. “To achieve our goal, we leveraged our experience in thin-film biocompatible batteries and design engineering to develop a bandage that creates mild currents to promote wound healing.”

While these alternatively powered wearables are still in development, wearables with traditional batteries but unusual capabilities are already hitting the consumer market.

PIVOT Yoga now sells clothing embedded with sensors that monitor your movements and send data to a companion app that provides feedback on your poses in real-time. Muse is one of several companies selling headbands containing sensors that track your brainwaves.

There’s even the Adam Sensor, a wearable that tracks nighttime erections—Johnson uses it to monitor his penis health, which can provide insights into more than just sexual function.

“Night time erections are an important biomarker for cardiovascular, neurological, or hormonal health,” he tweeted in 2024. “They indicate healthy blood flow and nerve function. No boners, no bueno.”

Deciphering data

Using wearables to collect data is just the first step to using them to improve your health—you then need to actually do something with the information.

For Johnson, this might mean dropping a new therapy because it was shown to reduce his deep sleep duration at night.

“Having a WHOOP as my feedback mechanism is extremely helpful,” he told Ahmed in 2023. “I’m trying things every single day, and I now have these deep intuitions on what will or won’t work….It’s nice to know I have this feedback device where I can feel it in the morning, but then the data confirms what I’m feeling is right.”

For someone who doesn’t know quite as much about health as Johnson or isn’t quite as in touch with their body, it can be hard to interpret all the data a wearable collects. Companion apps can help make sense of it, but navigating those can be tricky for the less tech savvy.

To help clear up any confusion users might have about their data and encourage them to take actions that will improve their health, WHOOP teamed up with OpenAI in 2023 to create WHOOP Coach.

“There’s been a lot of hype about the promise of AI. WHOOP Coach actually delivers on it.”

Will Ahmed

WHOOP Coach is accessed through WHOOP’s companion app, and like OpenAI’s popular ChatGPT, it’s built on a large language model, a type of AI capable of understanding and generating conversational language, the kind people use to talk to one another.

Users can ask WHOOP Coach about their data (“How did my sleep this week compare to last week?”), for training advice (“What would be a good exercise plan if I want to lose five pounds this month?”), general health questions (“What does HRV stand for?”), and more.

Unlike a human fitness coach, WHOOP Coach is available 24/7, and even if a user doesn’t have specific questions for it, the AI can generate a “Daily Outlook” that will provide recommendations for exercise, recovery, nutrition, and more based on data from their WHOOP.

“There’s been a lot of hype about the promise of AI. WHOOP Coach actually delivers on it,” says Ahmed. “With the launch of WHOOP Coach, we’re now offering on-demand, personalized health and fitness coaching. This is the first of its kind and it will transform our members’ relationship with their data.”

“I believe the future holds great promise for personalized health monitoring.”

Amay Bandodkar

WHOOP Coach might be the first of its kind, but it’s unlikely to be the last. Apple has been developing an AI health coach that will base recommendations off Apple Watch data since 2023, and Samsung is reportedly working on an LLM-based coach to integrate into its fitness trackers.

Between the development of these AI coaches and longer-lasting, more capable wearable devices, we could be heading toward a future in which even people who don’t have $2 million to spend on their health every year are able to live longer, healthier lives.

“I believe the future holds great promise for personalized health monitoring,” says Bandodkar.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].