This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Saturday morning by subscribing above.

It’s 2028, and for the first time in living memory, the US obesity rate is trending downward, and more and more Americans are achieving a healthy weight — potentially signaling the beginning of the end of the obesity epidemic.

The obesity epidemic

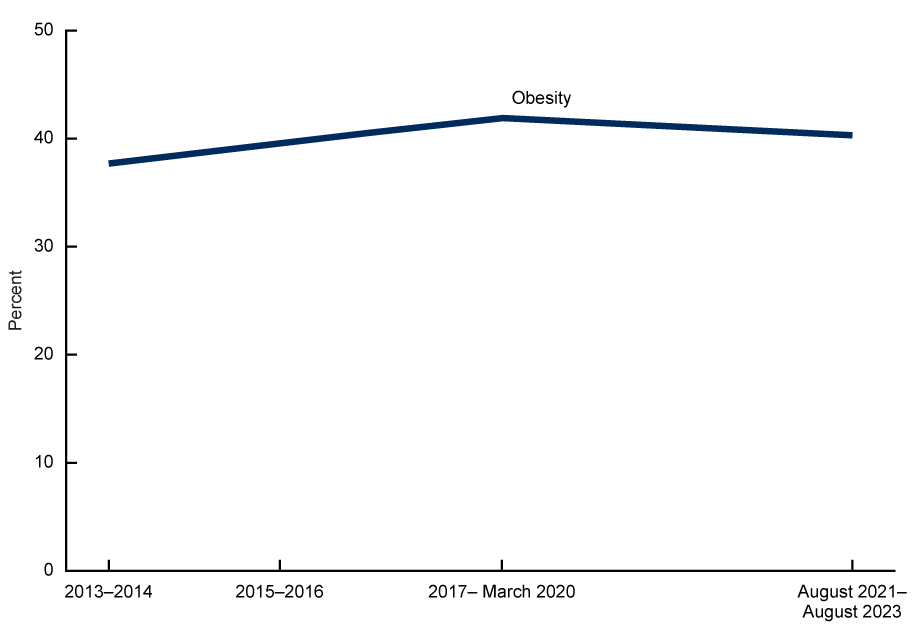

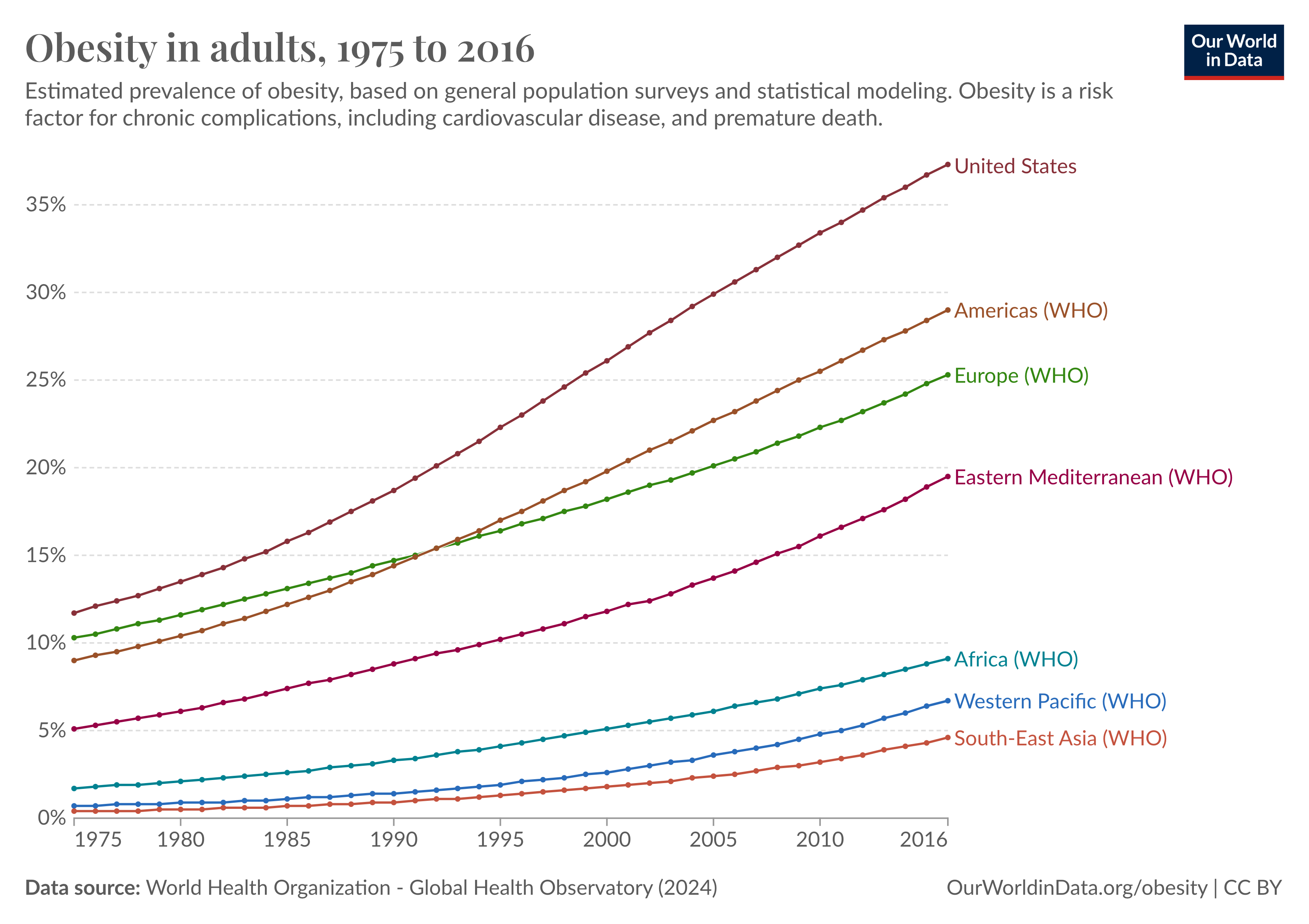

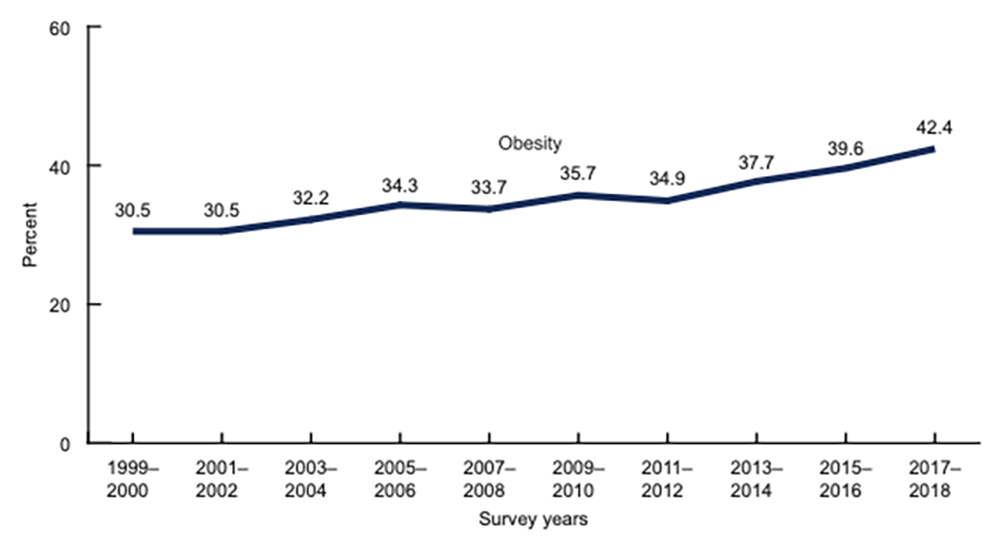

The US has a weight problem. According to the CDC, the percentage of Americans 20+ years old who classify as obese — meaning they have a body mass index (BMI) above 30 — has nearly tripled over the past 50 years, from 14.5% in the early 1970s to 40.3% in 2023.

However, that newest figure is slightly lower than the rate from 2020 (41.9%), causing some speculation that we have reached a turning point in the obesity epidemic. To find out whether that’s true — and, if so, what may be causing the trend — let’s explore the past, present, and future of obesity in America.

Where we’ve been

Obesity isn’t entirely a new phenomenon — archaeologists have uncovered sculptures depicting people with obesity dating back 30,000 years — and for much of human history, carrying excess weight was viewed as a sign of fertility and prosperity.

As far back as Ancient Greece, though, people were already connecting obesity to health problems, including early death, and their ideas for addressing excess weight focused on two things: diet and exercise.

“If we could give every individual the right amount of nourishment and exercise, not too little and not too much, we would have found the safest way to health,” reads the Hippocratic Corpus, written around 400 BC.

Fast forward about 2,400 years, and in many parts of the world, including the US, food has become both abundant and cheap, leading to unprecedented obesity rates. This, in turn, has led to higher rates of diseases and deaths linked to obesity.

Dropping excess pounds by moving more and eating less hasn’t gotten any easier over the centuries, either.

Despite countless diet and exercise programs designed to simplify the process, it still takes a lot of willpower to hit the gym consistently and eat the right number of calories. Our biology can actually work against us in the process, too — weight loss leads to lower levels of the hormone leptin, for example, and that reduction triggers feelings of hunger.

In the 20th century, the FDA approved a handful of medications designed to facilitate weight loss, but they haven’t been much help: many were later pulled, usually because they were deemed unsafe, and others had side effects that prevented them from becoming popular.

About 50 years ago, bariatric surgery emerged as an option for people with severe obesity or serious obesity-related health issues. It’s considered one of the most effective options, but adoption has remained low — only about 1% of Americans who qualify for the surgery get it, with cost, recovery time, and general fears of surgery contributing to the low rate.

Now, millennia after doctors first realized that obesity was a serious health issue, the number of people living with it is the highest it has ever been, and yet treatment options have remained basically the same: move more and eat less.

Where we are

After decades of increases in the obesity rate, the CDC survey showing a small decline is encouraging — 40% is still high (the CDC has set a modest goal of 36% by 2030), but perhaps we’ve hit “peak obesity” and will soon see rates of obesity-related diseases also start to fall.

Unfortunately, it’s too soon to celebrate. Obesity rates in the US have seemingly leveled off before, just to start increasing again soon after.

“I do not think we can make any predictions about obesity levels plateauing by comparing just two points in time,” Peter T. Katzmarzyk, associate executive director for population and public health sciences at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, told Freethink. “We need to look at longer-term trends over several time points, which indicate that obesity has been increasing over several decades.”

“It appeared that obesity was plateauing between about 2007-2012, but then started to increase again,” he added.

If the decline is real, though, a leading theory as to why is the recent development and approval of the new blockbuster GLP-1 agonist drugs — medications that mimic the activity of the hormone GLP-1, which is produced after you eat and suppresses hunger.

GLP-1 agonists were initially approved to treat diabetes, with approvals for weight loss coming later. In recent trials, the latest formulations were found to help people lose as much as 10-20% of their body weight, as well as reduce their risk of weight-related health problems, such as heart attacks and deaths from cardiovascular disease.

Between 2019 and 2023, the number of Americans taking a GLP-1 agonist for weight loss has increased by more than 700%, and as of May 2024, 6% of adults self-reported as taking one of the meds.

“Even if a notable minority is taking the drugs and losing weight, that’s going to alter the shape of the curve, the prevalence rates, and related statistics,” David Ludwig, an endocrinologist at Boston Children’s Hospital, told the Atlantic. “So it would be surprising, and very depressing, for us not to see any impact of these extremely costly drugs by this point.”

Where we’re going (maybe)

As Katzmarzyk noted, we won’t know for sure that obesity rates are actually leveling off or falling until we have longer-term data. We’ll then need to dig into it to figure out exactly what is behind the trend — new weight loss drugs seem like an obvious answer, but it’s possible other factors, like fewer people going out to eat, could be contributing, too.

If GLP-1 agonists are having a notable impact on America’s collective waistline, though, it’s worth considering whether the medications could be a permanent solution to the problem, and if so, how we could get them into the hands of everyone who could benefit from them.

“These are not miracle drugs.”

A GLP-1 agonist user

Losing weight is easier than keeping it off. Aside from our biological drive to regain lost weight, the motivation of seeing positive changes in the mirror, or in our bloodwork, while we’re losing weight can end once we hit our goal weight, making it easy to fall back into old habits.

Freethink spoke with three people currently using GLP-1 agonists for obesity, and all three reported feeling like they were in a much better position to maintain their weight loss on the drugs than they had been after losing weight through other methods in the past.

“Every diet that was available, I tried, and while I lost weight initially, it was really hard to sustain being on these diets for a long period of time,” a 38-year-old woman told Freethink. “Eventually, I got either bored of doing it or I wasn’t able to stick to it, and I ended up just gaining the weight back.”

Two years ago, she started taking a GLP-1 agonist and lost about 60 pounds in 10 months. Since then, she’d been focused on maintenance, which has been going better than it had in the past.

“I’ve been a little up and down with weight within 10 pounds,” she said. “Some of it has been due to an injury that I’ve had which prevented me from doing some of the physical activity I wanted. It also does get a little more tricky around the holiday season — I think that everybody struggles with that.”

This idea that the drugs alone aren’t enough to ensure permanent weight loss was another common thread in Freethink’s discussions with GLP-1 agonist users — all three emphasized that they also needed to (you guessed it) eat less and exercise more to reach their goals. The medications just made doing that easier.

“These are not miracle drugs,” the 38-year-old woman emphasized. “You don’t just give yourself an injection and poof, you lose weight. I started working out way heavier, doing a lot more cardio, and I started to change the foods that I ate.”

“The overwhelming majority [of patients] will need ongoing and chronic therapy.”

A Novo Nordisk spokesperson

Aside from sticking to a diet and exercise plan, people who lose weight with GLP-1 agonists typically need to stick with the drugs, too — patients tend to regain their lost weight if they stop taking their meds.

“Obesity is like other chronic cardiometabolic diseases which require ongoing treatment,” a spokesperson for Novo Nordisk, maker of the popular GLP-1 agonists Ozempic and Wegovy, told Freethink. “Just like hypertension, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol, you would never just stop your medicines.”

“There are always exceptions to the rule, as there are patients who lose weight with medication and then come off of it and keep the weight off, but the overwhelming majority will need ongoing and chronic therapy,” they continued.

Not only did the GLP-1 agonist users that Freethink talked to seem OK with the idea of being on the drugs indefinitely, two of them expressed trepidation at the thought of not taking them.

A 36-year-old woman who has lost 84 pounds on one of the meds said she was “scared” at the thought of quitting the drugs because she didn’t think she’d be able to maintain the weight loss on her own. A 63-year-old man who has lost 80 pounds said he was “a bit worried” about what might happen if he stopped.

“If my insurance was to stop covering it, then I won’t be able to afford it every month.”

A GLP-1 agonist user

While the three patients Freethink spoke to might want to stay on their meds longterm, there’s no guarantee they’ll be able to.

Right now, they’re each paying between $25 and $50 per month for their prescriptions through their health insurance plans. If insurance doesn’t cover it, though, the out-of-pocket costs for the meds can be as high as $1,300 per month, and about 55 million Americans living with obesity don’t have insurance that covers anti-obesity drugs, according to Novo Nordisk.

While some companies are adding GLP-1 coverage to their health insurance plans, others are going in the opposite direction and dropping it due to the high cost of the meds, meaning some people are being forced to stop taking the drugs even when they don’t want to.

“If my insurance was to stop covering it, then I won’t be able to afford it every month,” the 36-year-old woman told Freethink.

The bottom line

GLP-1 agonists aren’t going to be the answer for everyone with obesity. An estimated 20% of users don’t respond to the medications, and many can’t tolerate them — 17% of people who received Wegovy in one large trial quit due to the medication’s unpleasant side effects, which can include vomiting and diarrhea.

However, they are the most effective weight-loss medications available today, and even if it’s too soon to note any impact they’re having on obesity rates in the US, millions more Americans could potentially benefit from the drugs if we can increase access to them, which means addressing the cost issue.

The most straightforward solution there would be for pharma companies to lower the price. Pressure from policy makers could encourage this in the US, as could competition from new GLP-1 agonists and other types of obesity treatments — many are now in clinical trials, and some are even oral meds, which could be preferred over the currently weekly shots.

Further down the line, the patent for the drug in Ozempic and Wegovy will expire in 2032, after which cheaper generic versions will hit the market.

“Obesity is a complex disease that requires complex solutions.”

Peter T. Katzmarzyk

Pharmacological treatment alone might never be enough to lower America’s obesity rates, though — Katzmarzyk told Freethink he expects we’ll need to attack the problem from multiple angles.

“The reliance on individual-level treatment approaches is very time-consuming and expensive,” he said. “It is also questionable if we really can address the broader obesity epidemic by using approaches that affect one individual at a time.”

“Obesity is a complex disease that requires complex solutions,” he added. “We will need coordinated obesity treatment and prevention programs at the community and at the individual level.”

These community-level initiatives could include things like the creation of more bike paths and parks or supermarkets in places that are currently food deserts — basically, anything that lowers barriers to eating healthier and moving more.

“It really has been life-changing.”

A GLP-1 agonist user

Regardless of what it takes to get there, if the US can lower its obesity rate, the benefits could be wide-ranging: a healthier military, higher fertility rates, and huge economic savings — right now, obesity is costing the US healthcare system $173 billion a year.

For now, though, all we know for sure is that at least one approach to treating obesity is having a major impact on the lives of millions of individuals, helping them make the changes needed to lose weight, keep it off, and improve their overall health.

“When you start to see your cholesterol come down, when you see your blood pressure is under control, when you’re able to cut back on your other medications … it really has been life-changing,” the 63-year-old man told us.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].