It’s 2045, and you were just diagnosed with kidney failure. A couple of decades ago, this would’ve meant years of dialysis while you waited for a donor kidney to become available, but thanks to advances in cryopreservation, your doctor is able to order you a new organ from cold storage right away.

Cryopreservation

Cryopreservation — the process of freezing and storing biological materials for later use — has revolutionized healthcare.

Millions of people have started families using cryopreserved sperm, eggs, and embryos, and frozen ovarian tissue is now used to restore fertility in women who’ve lost it due to chemo. Cryopreservation has also allowed us to bank donations of rare blood types for transfusions, bone marrow for cancer-fighting stem cell treatments, and skin allografts for treating severe burn victims.

We may just be scratching the surface of what’s possible with cryopreservation — some predict it’ll one day help us end the organ shortage, survive terminal illnesses, and maybe even populate the solar system.

To find out how, let’s take a look at the past, present, and future of cryopreservation.

Where we’ve been

In the 1930s, farmers in the US, Russia, and other parts of the world were leaning into artificial insemination for breeding their livestock — not only did it have a better conception rate than natural reproduction, it also reduced the amount of semen needed for a pregnancy, meaning one high-quality male could impregnate more females.

One of the biggest challenges they faced, though, was getting the sperm into the females fast enough.

While mixing semen with an egg yolk-based “extender medium” and then cooling it to about 41 F extended its viability, farmers still had just a few days between when semen was collected and when it had to be used. Attempts to freeze, store, and then thaw it failed because ice crystals would form outside the sperm cells, causing damage that prevented conception.

“Time has lost its significance.”

Alan Sterling Parkes

A breakthrough came in 1949 when English biologist Christopher Polge discovered that he could produce healthy chicks from frozen and thawed chicken semen if he mixed glycerol with the extender medium — the compound acted as a “cryoprotectant,” protecting the sperm cells from damage during freezing. He soon refined the technique to work with bull semen, too.

“Time has lost its significance,” Alan Sterling Parkes, one of Polge’s collaborators, told the New York Times in 1951. “The vitality and fertility of the sperm will be retained for an indefinite period. An animal could be used as a sire long after its death. What is true of animals is also true of men.”

It wasn’t true of men right away, though — human sperm were still non-functional after thawing, even when frozen with glycerol.

Soon after Polge’s team’s breakthrough, though, American biologist Jerome Sherman started conducting his own cryopreservation experiments with human semen. He discovered the key to effectively cryopreserving it was to first use a centrifuge to concentrate the sperm. After mixing the cells with a mixture of glycerol and extender medium, he then had to freeze them slowly before storing them on dry ice.

In 1953, the first three human babies conceived using cryopreserved sperm were born, and before the end of the 20th century, researchers would discover the right combinations of techniques, cryoprotectants, and refrigerants to successfully cryopreserve human eggs, embryos, blood cells, skin allografts, and more, too.

Scientists and science-fiction writers alike would also be inspired to imagine a radical future use for the technology: freezing and storing whole people.

The theory was that a person could be cryopreserved after death and then revived whenever a cure for what killed them was finally available, be it years, decades, or even centuries later. In 1967, psychology professor James Bedford became the first person to have their corpse cryogenically frozen, and since then, an estimated 500 people have followed suit.

Where we’re going (maybe)

While the cryopreservation of cells and tissues is now routine in healthcare, the freezing and storing of whole human bodies shortly after death, also known as “cryonics,” is still rare and controversial.

Some question the morality of trying to “cheat death” with cryopreservation, while others argue that those selling the service are taking advantage of people who are sick or simply scared of dying — some cryonics companies charge $200,000 or more per body.

Even if future doctors could treat the cause of death in people who have been cryopreserved, there’s a good chance that the bodies would be too damaged to be revived — you need to use the right cryoprotectants, the right freezing and thawing techniques, etc. The horrific state of the ones that have been thawed and examined to date certainly doesn’t inspire confidence.

That doesn’t mean we’ll never be able to figure out the right way to cryopreserve humans, though — and along the way, we could achieve breakthroughs that are as impactful on healthcare as the freezing of embryos and stem cells.

“Cryobiology is an engineering problem,” João Pedro de Magalhães, head of the Genomics of Ageing and Rejuvenation Lab at the University of Birmingham and co-founder of biotech startup Oxford Cryotechnology, told Freethink. “We understand the biology — we just need to engineer the solutions to overcome the challenges and limitations we still have in preserving biological materials.”

“The problems get worse the bigger the tissue samples get.”

Ariel Zeleznikow-Johnston

One of the biggest challenges is that it’s much easier to get something small, like an embryo comprising just 100 or so cells, to freeze and thaw evenly than it is to do the same with larger biological materials, like whole bodies or even individual organs.

With those, the center of the object can take longer to freeze than the outer layers, and vice versa during warming — outer layers thaw faster than the core layers. In either case, the uneven temperatures can encourage ice formation and lead to cracking, tearing, and other tissue damage.

“The problems get worse the bigger the tissue samples get,” Ariel Zeleznikow-Johnston, a neuroscientist at Monash University, told Bloomberg in June. “You get these big differences in temperature gradients. People have tried to get around this with cryoprotectants, but they are toxic in and of themselves.”

In July 2023, scientists at the University of Minnesota (UMN) announced a breakthrough in combating this issue.

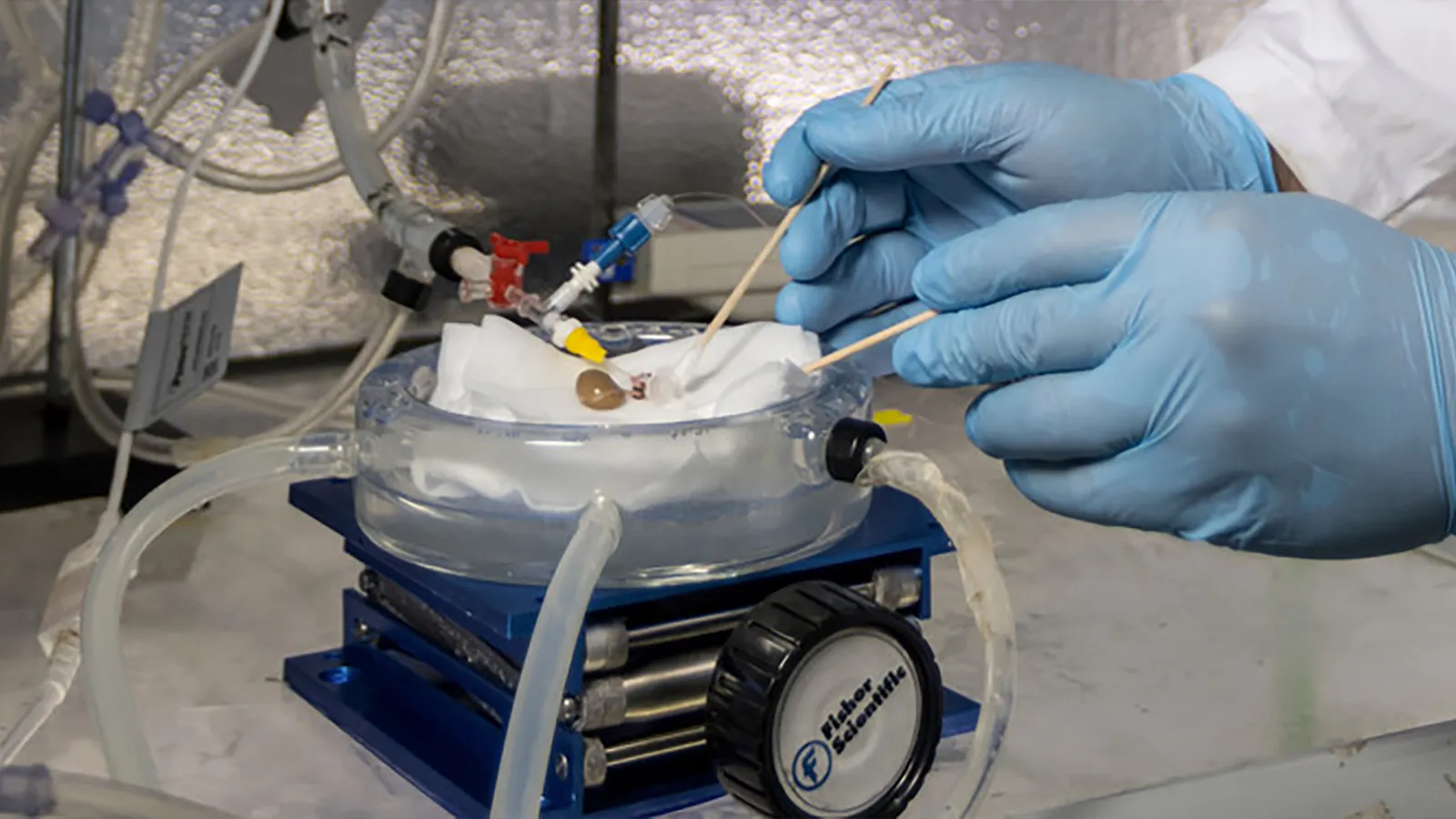

For a study published in Nature Communications, they mixed iron nanoparticles into a cryoprotectant solution before running it through the blood vessels of rat kidneys. Then, rather than slowly cooling them, they used liquid nitrogen to flash-freeze the organs. This approach, called “vitrification,” causes cells to take on a glass-like state and is widely used in embryo cryopreservation today because it leads to less damage.

After storing the kidneys for up to 100 days, the UMN team placed the vitrified organs inside a copper coil and ran a current through it. This created a magnetic field that caused the iron nanoparticles in the kidneys to heat up, which warmed them evenly in about 90 seconds.

The scientists then flushed the iron-containing cryoprotectant from the kidneys and transplanted them into five rats.

“During the first two to three weeks, the kidneys weren’t at full function, but by three weeks, they recovered,” said Erik Finger, the study’s co-senior author. “By one month, they were fully functioning kidneys that were completely indistinguishable from transplants of a fresh organ.”

“This is the first time anyone has published a robust protocol for long-term storage, rewarming, and successful transplantation of a functional preserved organ in an animal,” added John Bischof, the study’s other co-senior author.

“If we could cryopreserve human organs we could develop organ banking for transplants that would save thousands of lives per year.”

João Pedro de Magalhaes

Rat kidneys aren’t exactly huge — they typically weigh less than 1 gram — but they contain tens of millions of cells of at least 20 different types, making them way bigger and more complex than something like an embryo.

That someone was able to successfully freeze, thaw, and transplant any mammalian organ, regardless of size, marks a major milestone along the path to what many see as the next big goal of cryopreservation: human organ banking.

Donor organs do not last long outside the body. Surgeons have somewhere between six and 36 hours after removal, depending on the organ, to transplant them into a recipient, and even within that window, a longer delay can mean a worse transplant outcome.

If we could cryopreserve donor organs for later use, we could potentially end this race against the clock and improve transplant outcomes — organs could be stored for days, weeks, or even years before use if needed.

We could also increase the supply of donor organs, which currently falls short of the demand. Every year, thousands of donated organs are discarded in the US because doctors turn them down, and the time the organ has been out of a body is one of the factors they consider when making this decision.

“The bottom line is that if we could cryopreserve human organs we could develop organ banking for transplants that would save thousands of lives per year,” Magalhaes told Freethink. “It would be a major medical breakthrough.”

“I think in the next 10 years we will see cryopreservation … and revival of small rodents.”

João Pedro de Magalhaes

The UMN team recently told Chemistry World that it is already working to scale up its technique to larger organs, though it isn’t ready to publish anything on those studies just yet. Magalhaes, meanwhile, is optimistic that an even greater milestone in cryopreservation is now within reach.

“I think in the next 10 years we will see cryopreservation … and revival of small rodents, which will be important for raising awareness and bringing more attention to the field,” he told Freethink, noting that this could lead to an increase in funding for cryobiology, which is currently a small field.

This funding could go farther today than at any time in the past, too, as scientists could use the data generated by any new experiments to train AIs that could help us solve existing challenges in cryopreservation.

Oxford Cryotechnology is already developing AI models to help identify new cryoprotectants, and Magalhaes told Freethink that that’s just one potential application: “In addition to new cryoprotectants, AI can help in many other ways, for instance, optimising concentrations and temperature gradients for cryopreservation of different cell types and tissues.”

An AI is only as good as its training data, though, and because cryobiology is such a small field, there isn’t a ton of high-quality data, hence the need for more funding to generate it.

“Think the hibernation pods you see in space movies for long-term travel – we want to build that.”

Laura Deming

It’s possible that Cradle Health will be the group to achieve the whole-rodent breakthrough that Magalhaes thinks will inspire this funding.

The startup, which was founded by biotech prodigy Laura Deming and has raised $48 million in investment, announced in June that it had vitrified and rewarmed slices of rodent brain tissue in a way that allowed the tissue to retain some of its electrical activity after thawing — a first in the field of cryopreservation.

Cradle hopes to crack the code on cryopreserving human organs before moving on to whole rodents, but its long-term goal is to freeze humans, specifically ones who are sick with terminal illnesses so that they could “hibernate” until a cure is found.

“Think the hibernation pods you see in space movies for long-term travel – we want to build that,” Deming tweeted about her new startup.

If Cradle — or any other group — is able to successfully cryopreserve and revive humans, it’s possible the tech would be applied to space travel eventually. A trip to somewhere as “close” as Jupiter is likely to take years, and being able to “cryosleep” through journeys to deep space could protect astronauts’ mental health and eliminate the need to pack food for the trip, saving room and cutting costs.

It’ll likely take decades to get there, but as Magalhaes said, cryopreservation is largely an engineering problem. If we keep chipping away at it using the latest available technologies, we could potentially manifest a future in which we’ve ended the organ shortage, indefinitely delayed death, and enabled the exploration of the universe far beyond our planet.