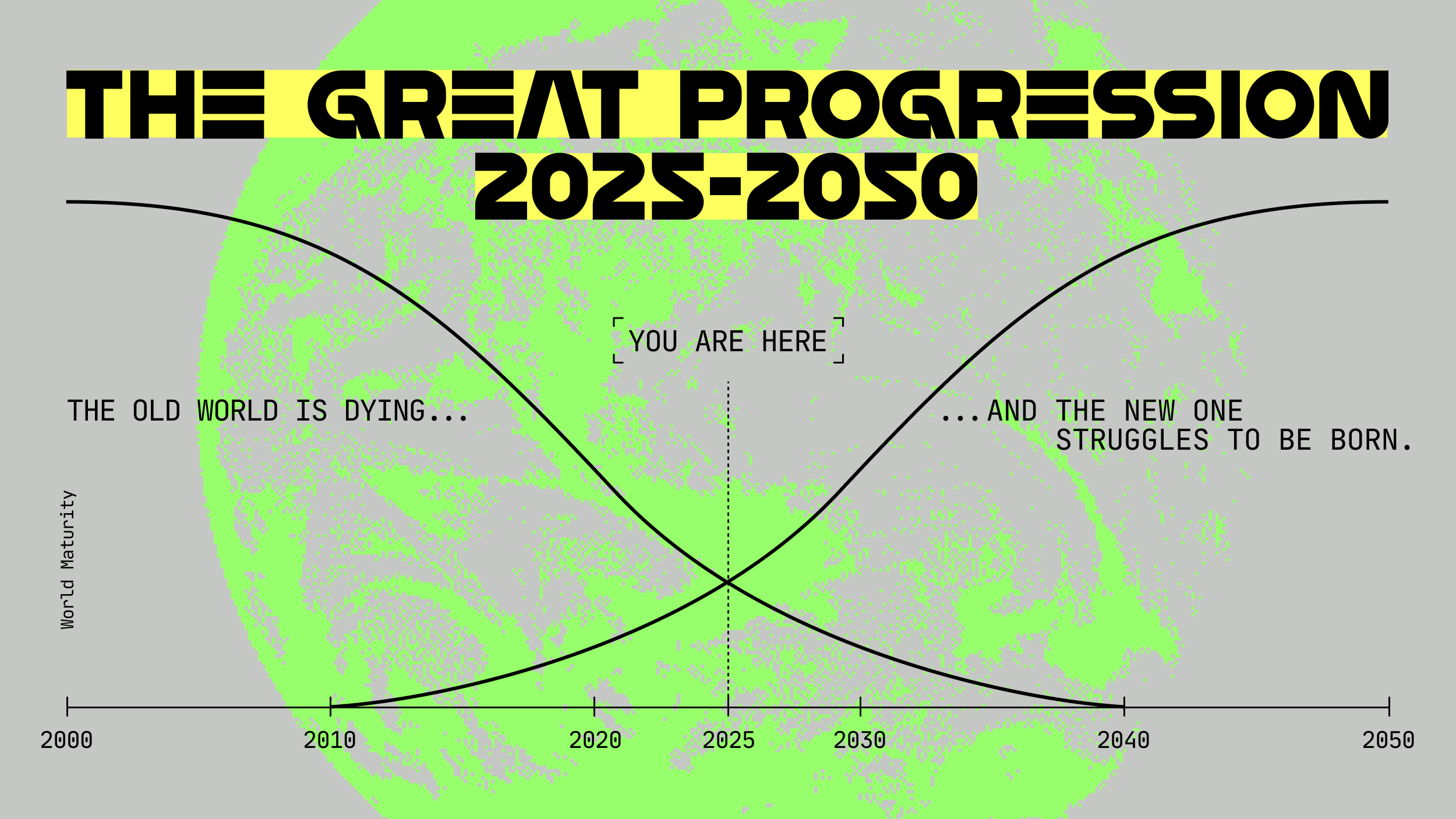

The last time America went through anything comparable to what we are going through today, it was coming off the Great Depression and World War II and about to head into the post-war economic boom, as represented in the graphic above.

America in the year 1945 and America in 2025 have many parallels that are worth contemplating today. Like today, that America faced a rare epic juncture in the nation’s history and even in world history. The technological and economic forces driving through the era were just as transformative as today’s, and the political stakes around the outcome were just as high. The systems that were about to scale up in the next 25 years for them were dramatically different from the systems that came before — just like the systems that are about to scale up for us.

America has been through this drill before, like exactly 80 years before, but what’s even more remarkable is that we have been through this kind of fundamental reinvention two other times in the history of the country — once around the Revolutionary War in the late 18th century and then again around the Civil War in the middle of the 19th century. The most uncanny thing about this cycle of reinvention is that each one happens almost exactly 80 years after the last.

The more you understand this pattern of the past, the more you will understand what’s really going on today.

This essay is going to lay out the remarkable parallels between today’s America and the nation during each of its previous periods of fundamental reinvention. It will compare our pivot year of 2025 to the previous pivot year of 1945 and the end of World-War II, and then to the end of the American Civil War in 1865, exactly 80 years prior. It will then go back another 80 years to 1785, just after the Revolutionary War as the founders were gearing up for the Constitutional Convention.

In each of these periods, Americans found themselves at a juncture. The old systems that had long served them well had been breaking down over the previous 25 years and needed to be superseded. At the same time, they were facing a period of explosive growth — driven by new technologies that required widespread innovation throughout the economy and society — that would last for the next 25 years. The graphic above captures that juncture between the old world dying and the new world struggling to be born in 1945.

At each of these junctures, smack in the middle of the dying world and the new world struggling to be born, political passions run extremely high, and the country polarizes around two political options for its future. The more you understand this pattern of the past, the more you will understand what’s really going on today.

My new series, The Great Progression: 2025 to 2050, will go beyond explaining today, and explain what the next 25 years of our coming long boom could bring. The graphic above from the initial overview essay shows what’s happening now and can act as a reference point when looking at the comparable graphics for our past historical eras.

Much of the material to come in this series will be future-focused. I’ll detail our opportunity to harness the world-historic general-purpose technology of artificial intelligence to transform our economy and society in myriad ways. I’ll also explain how other transformative technologies, such as clean energies and bioengineering, could be used to bring fundamental system changes and help solve the most daunting challenges that we now face.

But to help convince you to take these future projections seriously, I’m going to walk you through the three other times America has faced a comparable historic juncture and met the moment with a fundamental reinvention that lasted roughly 25 years and created models that helped point the new way forward for the rest of the world.

The post-World War II boom and the remaking of the international order

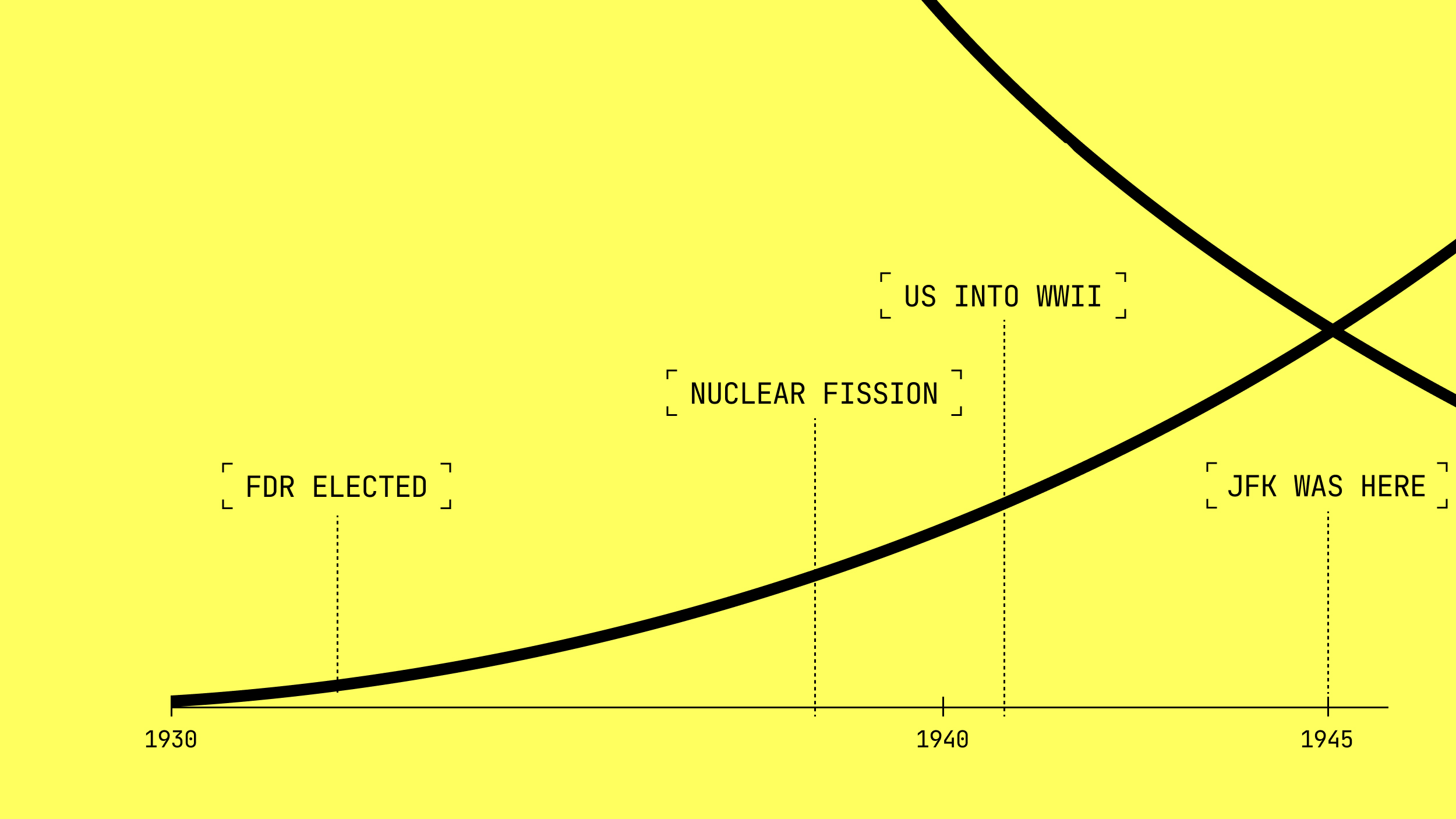

If you have any living relatives from the GI Generation, ask them to explain what they know about the last great period of American reinvention, which is captured in the graphic at the top of this piece. (My 95-year-old mother is among the last of that generation, and I am doing just that.) This is not ancient history — this is within living memory of some Americans still with us today.

The GI Generation has been called the Greatest Generation, and that’s because its members, including John F. Kennedy (JFK), not only fought against fascism as young people in World War II, but also, just as importantly, helped build out the new America and new world order in the great boom that followed, with JFK becoming the first of seven US presidents from the generation. They were the players during this crucial juncture. What did they experience?

By the time World War II ended in 1945, the GI Generation and all Americans of that era had already lived through several major developments that have parallels today. They had watched the rapid deterioration and dysfunction of the old economic systems that worked relatively well for previous eras — until they didn’t. At the end of the Roaring Twenties, they saw the great stock market crash of 1929 and the beginning of the Great Depression, a period of widespread unemployment and hardship for the vast majority of working people not just in America but throughout the developed world.

By 1945, Americans had lived through a period of ferocious domestic politics with two sides in a titanic struggle that often flirted with violence but stopped short of outright civil war. The more conservative side was marked by the rise of the America First movement and an American version of fascism that increasingly took over the Republican Party through the 1930s. The other, more progressive side was marked by the emergence of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) and a new kind of Democratic Party that tried out early experiments in what scaled up into the modern welfare state after WWII. (See the graphic at the top of this section.)

In the pre-war period, Americans watched the rise of the new powers of Japan and a resurgent Germany and endured a period of such ferocious geopolitical struggle that it led to an all-out world war. By 1945, the entire international order needed a wholesale reinvention — and that’s exactly what happened. In just a handful of years, the world saw the creation of the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, NATO, and many other completely new international institutions.

The level of reinvention on the domestic front after the war was just as extraordinary. Americans of that era seized on the new technologies that had emerged before and during the war and dramatically scaled them up. Nuclear fission was only discovered in 1938, but after the war, the nuclear power industry exploded in growth alongside our nuclear bomb arsenals. Many of the technologies developed before the war and refined during it — such as mainframe computers, commercial aviation, and plastics — were poised to take off after its conclusion.

The point of revisiting this 20th century history is to help you see all the parallels to our American moment.

The post-war boom brought an incredible build-out of new public infrastructure in the form of the interstate highway system, suburbs outside of all central cities, and a huge expansion of schools and institutions of higher education to accommodate the Baby Boom.

The economy was deliberately and fundamentally restructured to avoid the mistakes of the old system, which had led to huge wealth inequalities and the financial crash and depression. The rich were taxed 90% on income in the highest tax bracket — that rate had never been contemplated before, but it stayed in place for 20 years. America built its version of a welfare state that protected average workers and citizens, and it led to a big push for the Great Society programs and the expansion of civil rights in the 1960s.

All of this happened in the space of just 25 years after the war, from 1945 to 1970. During this period, similar changes occurred throughout Europe and the West, but by the 1970s, the entire post-World War II boom, what many have called the Golden Age of Capitalism, had started to slow with oil shocks and stagflation.

The point of revisiting this 20th century history is to help you see all the parallels to our American moment. We have our own old 20th century systems that are breaking down and causing more problems than they solve. If you’re on the right, you will rail about the old bureaucratic systems of government. Fair enough. If you’re on the left, you will rail against old carbon energy systems that are causing catastrophic climate change. True too.

We also have our versions of transformative general-purpose technologies. Clean energy in the form of solar cells and electric vehicles are poised to replace carbon energies and the internal combustion engine. We have bioengineering tech that could create materials to supersede plastics. Artificial intelligence, the most transformative technology of all, is ready to reinvent pretty much everything.

We have our version of a ferocious domestic political struggle that is far from settled, too. President Donald Trump and his MAGA Administration have won the most recent battle, but that isn’t the same as winning the war. He is accelerating the dismantling of the old domestic bureaucratic state and the Pax Americana, but he seems to have no real plan for what to build in its place. The story of the next 25 years is just beginning.

But that will take another essay. Let’s go deeper into American history for now.

The 80-year American reinvention that actually went into Civil War

Go back another 80 years from 1945, and you arrive at 1865 and the end of the Civil War, the most ferocious political battle Americans have ever gone through. By the time we finally settled that one, 750,000 Americans were dead.

This juncture is the best one to drive home the point about why political passions run so high at these historic moments: They mark fundamental system changes, and the stakes are extremely high, particularly for those on the side of the system that has to die.

In the 1850s, America started facing up to the fact that its economy was built on two fundamentally incompatible systems: one based on free labor essential to a growing manufacturing economy in the North, and one based on slave labor essential to the agricultural economy of the South. These two systems had been in tension from the founding of the country, but the contradictions had become unsustainable by the middle of the 19th century.

Freeing the slaves was framed as a human rights issue, but it also was an economic issue that was central to how the political and economic system of the Southern states worked. The political leaders and economic powers of those conservative Southern states were so threatened by the looming system change of dismantling slavery that they banded together in the Confederacy and declared a war of secession.

The war took four years to resolve the slavery issue once and for all, but once settled, America went into an explosion of reinvention that rolled out for the next 25 years. The most dramatic difference came to the South with what we call the Reconstruction, which is another way of saying the Reinvention.

Each of these American reinventions is partly driven by new technologies that have reached the point where they can start to scale.

The Reconstruction started out as an idealistic plan to reinvent the Southern states, primarily through integrating freed slaves into the free market economy and giving them the vote. We added the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution and kept troops stationed throughout the South to enforce myriad changes. We now look back on the Reconstruction more as a failure than a success because white powerbrokers unwound many of the reforms and undermined the voting rights of former slaves for all practical purposes when these troops were pulled out in 1877.

America as a whole after the war went through an unambiguous period of great progress from 1865 to 1890. Although President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated just days after the end of the war, during his time in office, he and the progressive Republican Party that dominated Congress passed laws that helped transform the country in the coming decades.

The Homestead Act, which gave 160 acres of free land to settlers, drove westward expansion and became a cornerstone of that era’s version of the American Dream. The Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act dramatically expanded access to higher education for average Americans and spurred scientific advancement in many industries. Lincoln also signed the law that funded the Transcontinental Railway that eventually reached all the way to San Francisco.

The mention of trains brings up the technological side of all these historic junctures. Each of these American reinventions is partly driven by new technologies that have reached the point where they can start to scale and so more fundamentally transform the country. The discovery and early development of the new tech comes in the 25 years prior to the inflection point, but its major impact comes in the 25 years after we cross it.

America had seen trains before the Civil War, but they were small scale and centered around cities — the entire country had less than 30,000 miles of iron track. By 1890, though, the nation had about 170,000 miles of track connecting the entire continent. Thanks to the revolutionary Bessemer steel process, these tracks could be made of steel, too, which was more durable, safer, and capable of supporting heavier loads. With an ability to move freight and luxury passenger cars anywhere, America was a different nation.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” That’s the opening line of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which some of you can probably recite by heart.

A “score” meant 20 years, or the span of a generation, in the formal language of Lincoln’s time, so “four score and seven years ago” was his way of saying “87 years ago.” Travel 87 years back from 1863, the year Lincoln gave his speech, and you arrive at 1776, the year the Declaration of Independence was signed.

With the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln was saying that America was founded 87 years ago, and now, Americans of his era were being called upon to refound the nation on the principle that all men are created equal — for real this time. He was calling for a reinvention of America two years before the war was won.

So now let’s go back another “four score” years in American history, from the end of the Civil War in 1865 to 1785, when our founders were gearing up to invent America for the very first time at the Constitutional Convention.

The original American founding and key role in The Enlightenment

Now the story gets a bit more complicated because we need to step further back to take in an even bigger picture.

The United States in 1785 was a dinky nation of barely 4 million people scattered across 13 former British colonies stretching along the long coast of the Atlantic. The best way to understand the America of that time is to think of it as part of a much bigger Western Europe that was going through civilization-scale change in what we now call The Enlightenment.

The Enlightenment lasted from roughly 1680 to 1800, and during it, this expanded version of Western Europe created nothing short of a new civilization based on the invention of at least six new foundational systems that we are still working within today.

I’ll later do a whole essay on this, but for now, think of those core inventions as mechanical engines, carbon energies (starting with mined coal at scale), industrial production, financial capitalism, nation states, and, finally, representative democracy.

In other words, The Enlightenment invented six things with the potential to fundamentally change the world (and that did change the world with time). A couple of them had to do with foundational technologies, a couple laid the foundation for a different kind of economy, and a couple, introduced at the end of the period, laid the groundwork for a new kind of politics and government.

To give credit where credit is due, the nations of Western Europe, particularly Great Britain, invented the first five of these. But the former colonies of the United States can take credit for inventing representative democracy. (France gave it a shot around the same time but ended up devolving into a dictatorship.)

A very different world is now within reach.

The point is that what America invented from 1785 to 1810 was a civilization-scale innovation with ramifications for the entire world. The founding fathers wiped clean the proverbial whiteboard and started sketching out how a nation of free and equal people could create a true democracy — one that captured the will of the majority of people, but also protected the rights of the minority in a pluralistic society and that was built to withstand the return of tyranny. They came up with a plan that they concretized in a constitution, established a way to amend it over time, and then started the grand experiment.

The point of this essay is that America might be at another historic juncture of that magnitude. We in 2025 might be at the point of having to face up to what it would take to fundamentally invent a new kind of civilization.

Why? The shortest answer is the arrival of artificial intelligence, which signals the beginning of an age of intelligent machines. This world-historic development will increasingly allow humans to actually do a wide range of things that humans in all previous eras would only understand as magic.

Beyond AI, there’s a wave of other potentially world-changing 21st-century technologies, including tools that give us the ability to bioengineer all living things. Soon, we may be able to create abundant clean energy with the fusion process powering the stars. A very different world is now within reach.

America may be entering a time of such fundamental invention that we need to go back to the spirit of the founders, clean the proverbial whiteboard, and start sketching out how to invent new economic, societal, and governmental systems that take full advantage of 21st-century technologies and our new knowledge of how the world actually works — and how it can now be made much better.

At the very least, we’re due for America’s standard every-80-year reinvention. Even if it’s “only” as significant as the one the nation underwent after WWII, that level of change might be more than enough for some people.

The Great Progression: 2025 to 2050 series of essays, interviews, and gatherings is my attempt to help figure out what we could do in the next 25 years to pull off this next reinvention of America in a way that benefits the vast majority of Americans but also works better for everyone on the planet over the long haul.

If that sounds overly ambitious, that’s because we’re living through an extraordinary moment in history that calls for thinking way outside the box. If you are interested in a project of that epic scope, then join my Substack network and help me figure this out.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].