Blue America is abuzz with talk of a new politics of “abundance” these days, particularly since the March 2025 publication of a book with that name by The New York Times’ Ezra Klein and The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson. I’ve read the book, attended one of two huge book events that the authors held in San Francisco, and have been following the burgeoning conversation around it in the mainstream press, too.

I’m all for members of the Democratic party, the progressive movement, and the rest of Blue America talking up the potential to create a new politics of abundance, one in which our political and economic frameworks are focused on creating the conditions that allow us to produce more of everything for everyone, rather than on fighting over who gets what in a world of scarcity.

Many of the ideas in that new book — and the conversations surrounding it — focus on how we can shift the general mindset of those who are left-of-center from scarcity to abundance, from saying “no, stop” to saying “yes, go.” That’s a good first step.

Most of the specific ideas of what to do focus on how we could change current government policies and processes that get in the way of America being able to build anything quickly and easily anymore. That is necessary, for sure.

Those who talk up abundance have a generally positive attitude about new technologies. They want to develop a growing economy and are optimistic about the future. All this is good, too.

However, I don’t think most people currently making the case for abundance are making the full case when it comes to new technologies, so I am going to make that tech case in this essay, starting with this clear point: The arrival of artificial intelligence and other world-historic technologies is what is giving America and the rest of the world the opportunity to create a new era of great abundance.

We now have the technologies needed to build a new kind of economy and society that could work much better for everyone.

Artificial intelligence has the potential to dramatically increase the productivity rates of all knowledge workers and, once robotics develop a bit more, the productivity rates of all manual workers, too. The key driver of economic growth is the productivity rate, so we are going to see the beginning of a long economic boom soon. Long booms create new jobs, new wealth, more prosperity, and more abundance.

Clean energy technologies, such as solar power and batteries, have helped us make the shift from energy sources burning commodities to energy sources being technologies for the first time. Now that we have energy technologies, we can keep driving costs down until energy is cheap. The bonus is that these new energy sources are clean, so they will help us solve climate change, too.

On the horizon, we can see bioengineering and our deepening understanding of biology bringing many new ways to drive down the preposterous costs of healthcare, too.

A new era of great abundance will not just come because we build a movement or reform obstructive government processes. It will come because we now have the technologies needed to build a new kind of economy and society that could work much better for everyone.

The tech world has been speculating on this potential for at least 15 years. In fact, techies in the San Francisco Bay Area were all abuzz in 2012 following the publication of another “Abundance” book with exactly the same name, this one written by Peter H. Diamandis and Steven Kotler. They speculated on how a wide range of emerging technologies, including the three big ones mentioned above, could potentially bring abundance.

We need to now sync up the new political abundance movement with the tech crew already promoting it. Together, they can make a much stronger pitch to the American public that we could be on the verge of creating a much better world.

AI could bring down the prices of many costly services that stymie us today

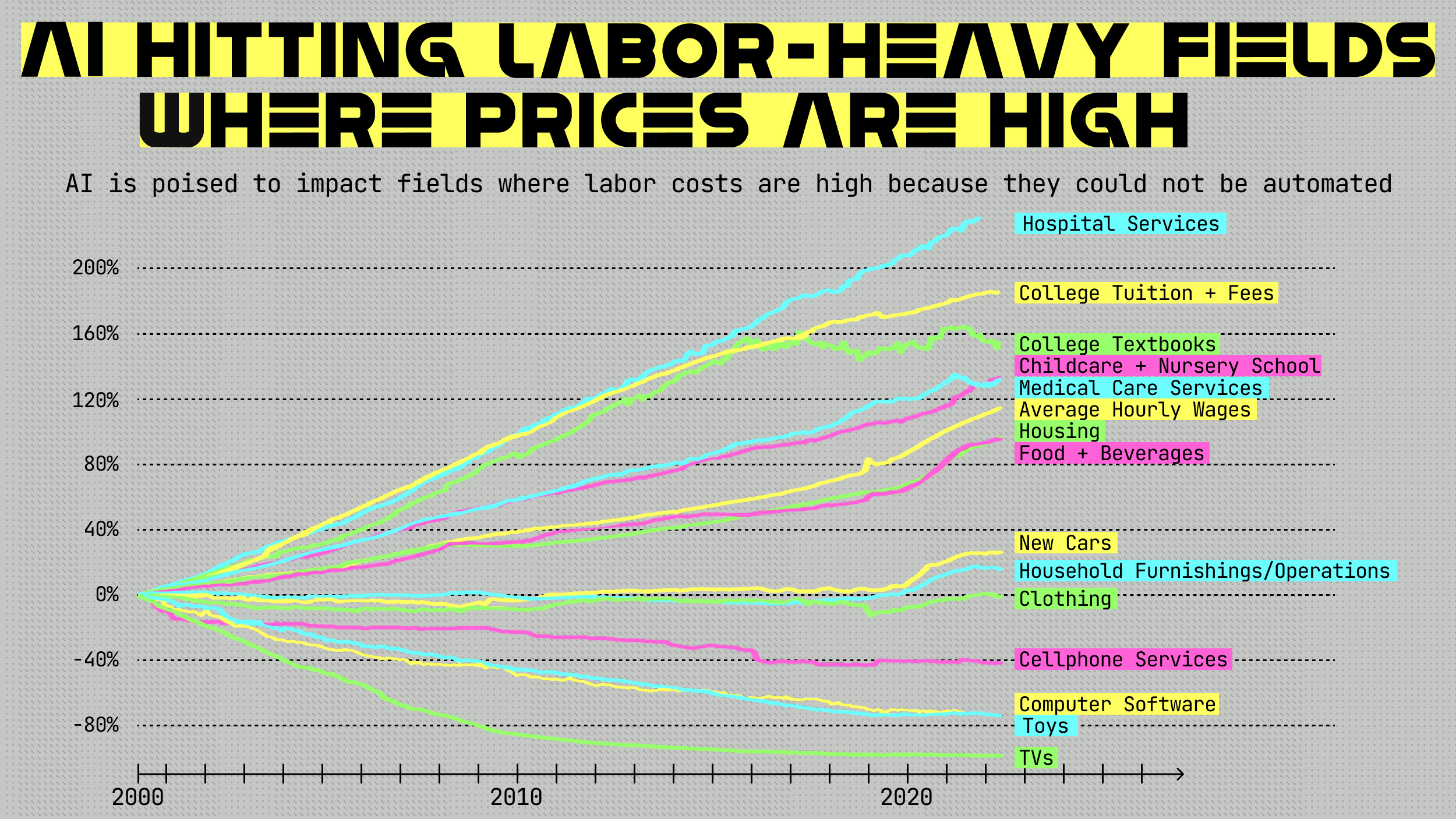

When you look at the prices of key goods and services in America over the last 25 years in the graphic below, you can see two main groups: those that went up in cost and those that stayed flat or declined.

Those that stayed flat or declined were mostly related to industries that use highly automated processes to produce goods or deliver services, such as the auto industry. In other words, they use technologies that greatly improve the productivity of workers. (Some of the examples, such as toys, arguably fell in cost because makers are also using cheaper labor from the developing world.)

The goods and services that increased in cost were in fields with high costs of labor, and their labor costs were high because the goods and services required intelligence to produce and deliver, respectively. For those 25 years, these jobs could not be automated because we simply did not have technology capable of carrying out even simple tasks that require intelligence.

In just the last couple of years, though, we have crossed a historic threshold with the arrival of intelligent machines. We now have machines that can sense the world around them, reason about how that world may or may not change, and then make decisions about what to do. For all of human history, we needed a biological brain to do that for even the simplest tasks. Now a machine can do it, too.

We’re just about to enter a transition period that might last a decade or two. During it, tasks that require intelligence will be divided into two groups: those that intelligent machines will now do, and those that humans will continue to do. Many of the tasks that machines do will be the simple, tedious, and boring ones that people might be fine handing over (set aside for now the implications on income and making a living). Some will be challenging jobs that replace highly educated humans, too.

On top of that, the people doing jobs that still require humans will be at least twice as productive because they will be augmented by intelligent machines. Every knowledge worker will have a virtual executive assistant to complete their tedious tasks and paperwork, freeing them to focus on higher-level work. They probably will have a virtual research assistant, too.

The result will be that the costs of many products and services that have kept going up for 25 years will now start coming down. Lower prices will make those services accessible to more people, which makes them more abundant.

In a world of abundance, everyone would have the opportunity to pursue higher education.

Take higher education, a service that has gone so far up in price that many middle-class families in America can now barely afford it. Why are the prices so high? One reason is that higher education uses a model of educating students that has not evolved much for hundreds of years. If Thomas Jefferson could walk into the University of Virginia that he founded, he’d find its lectures, seminars, and exams quite familiar.

Higher education has resisted any kind of automation over the decades and has not made teachers much more productive. Maybe that was all the institutions could do given the technological realities of the time, but artificial intelligence now brings the possibility of individual tutors for all students. Seen from the teacher’s perspective, this means a teaching assistant for each student in their class, which can make the human teacher much more productive — they can impact more students, cover more material, and innovate.

Over time, artificial intelligence could bring down the costs of higher education and make these learning opportunities far more abundant.

In a world of scarcity, rich or affluent people always had access to tutors. Upper-middle-class Americans could afford to hire people to help their kids prep for the SAT and the like. And those same families could pay for higher education despite the extremely high costs, too.

In a world of abundance, everyone would have the opportunity to have their kids tutored, and we’d all be able to pursue higher education. A politics of abundance might be able to use policy changes, most likely involving subsidies, to make that happen for some people, but the technologies of abundance, such as AI, can actually make it happen for all.

I could run through all the industries with the highest rise in costs from the chart above and give some version of what I just did for higher education. I could explain why the current costs are so high because of intelligent labor, and what AI might do to help bring those costs down, too. But let’s shift the argument to energy instead.

The next wave of clean tech could make energy cheap and abundant for all

Abundant energy is the holy grail of any civilization. The more energy a civilization can harness, the more it can do, and the more sophisticated it can become. You could even boil the insight down to this: The level of sophistication of any civilization is a function of the amount of energy it can harness.

Modern civilizations have an additional requirement. The success of previous civilizations in harnessing a sequence of carbon energies that have inadvertently changed the climate of the planet means our holy grail is abundant clean energy.

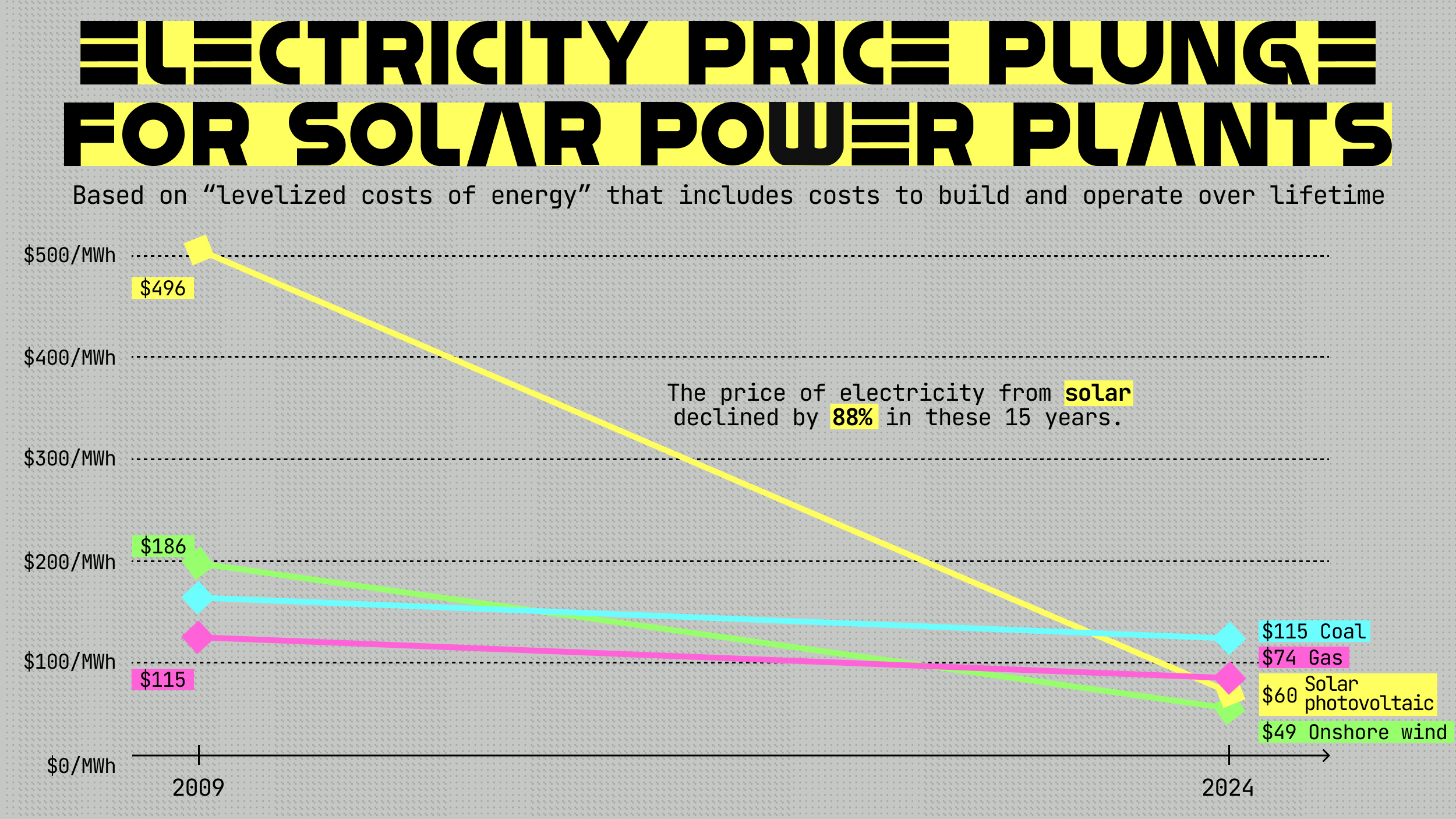

Humans have just crossed the threshold into an age that can deliver abundant clean energy. We have cracked the code on how to produce solar photovoltaic cells at costs that have dramatically dropped in just the last 15 years. As you can see in the graphic below, the price of electricity coming from solar power plants has fallen by 88% in those 15 years.

Solar power plants now produce electricity more cheaply than any power plant burning carbon energies, even the cheapest ones using natural gas and certainly the dirtiest ones using coal. No one in America is building coal plants anymore, and not just because of climate change — they are simply too expensive compared to solar.

Here’s the incredible part: Solar is going to keep getting cheaper and cheaper because it is a technology. The general rule of thumb in manufacturing solar panels is that every time you double the number of panels you produce, you bring costs down by about 20%. Pretty soon, solar panels will be so cheap that they will be plastered everywhere in the developed and developing world.

So, energy is transitioning from expensive and dirty to cheap and clean. This means we are moving from a world of energy scarcity to one of energy abundance.

I’ll give you a personal example. I installed solar panels on the roof of my house in the San Francisco Bay Area about eight years ago, and they are now fully paid off. I also have a home battery to store the energy that my panels capture, and my wife and I drive only an electric car.

I don’t care about saving energy. I can leave my home’s lights on all night. I can drive anywhere I want in the region. It costs me nothing. Zero. Everything I use in terms of energy, the sun will replenish for free the next day. And because the energy is clean, being renewable, I’m not adding any carbon to the atmosphere and ratcheting up climate change.

I’m a microcosm, a prototype, for what all of America could become over the next 25 years. And when America gets to the point of having abundant clean energy, we can do crazy energy-intensive things, such as desalinate water from the oceans to make fresh drinking water when the droughts come.

If abundant clean energy is the holy grail of any civilization, then fusion energy is the holy grail of clean energy itself.

To be sure, super-cheap solar alone won’t be able to meet all of our energy needs. Electric vehicles and AI data centers are going to create a huge demand for energy, and to meet it when the sun (and wind) aren’t producing, we will probably need to turn to the next generation of nuclear energy technologies, which release no carbon and are clean, too.

And then there’s the promise of fusion energy, which could become commercially possible within the next 25 years and almost certainly sometime this century.

If abundant clean energy is the holy grail of any civilization, then fusion energy is the holy grail of clean energy itself.

Fusion is how the sun and the billions of stars throughout our galaxy power themselves. Mastering the fusion of the universe’s simplest atoms to generate insane amounts of clean energy seems to be a worthy goal.

Our most advanced labs already have figured out how to fuse atoms, and in just the last few years, they’ve gotten to the point that more energy is coming out of the experiments than is needed to trigger these reactions. That’s a must-have to make fusion a viable source of clean energy, and a bunch of startups are now eyeing commercialization by the 2030s.

But that takes another essay to lay out. Now on to bioengineering.

As we bioengineer living things, we could create a new era of healthcare

I was beating up on higher education for its extremely high costs earlier in this piece, but I saved the best punching bag for last: healthcare.

I don’t think there is a rational person in the US who would disagree with the statement that American healthcare costs are preposterously high. And anything that costs that much is going to be scarce.

So, America is about as far as a nation could be from healthcare being cheap and abundant — or is it?

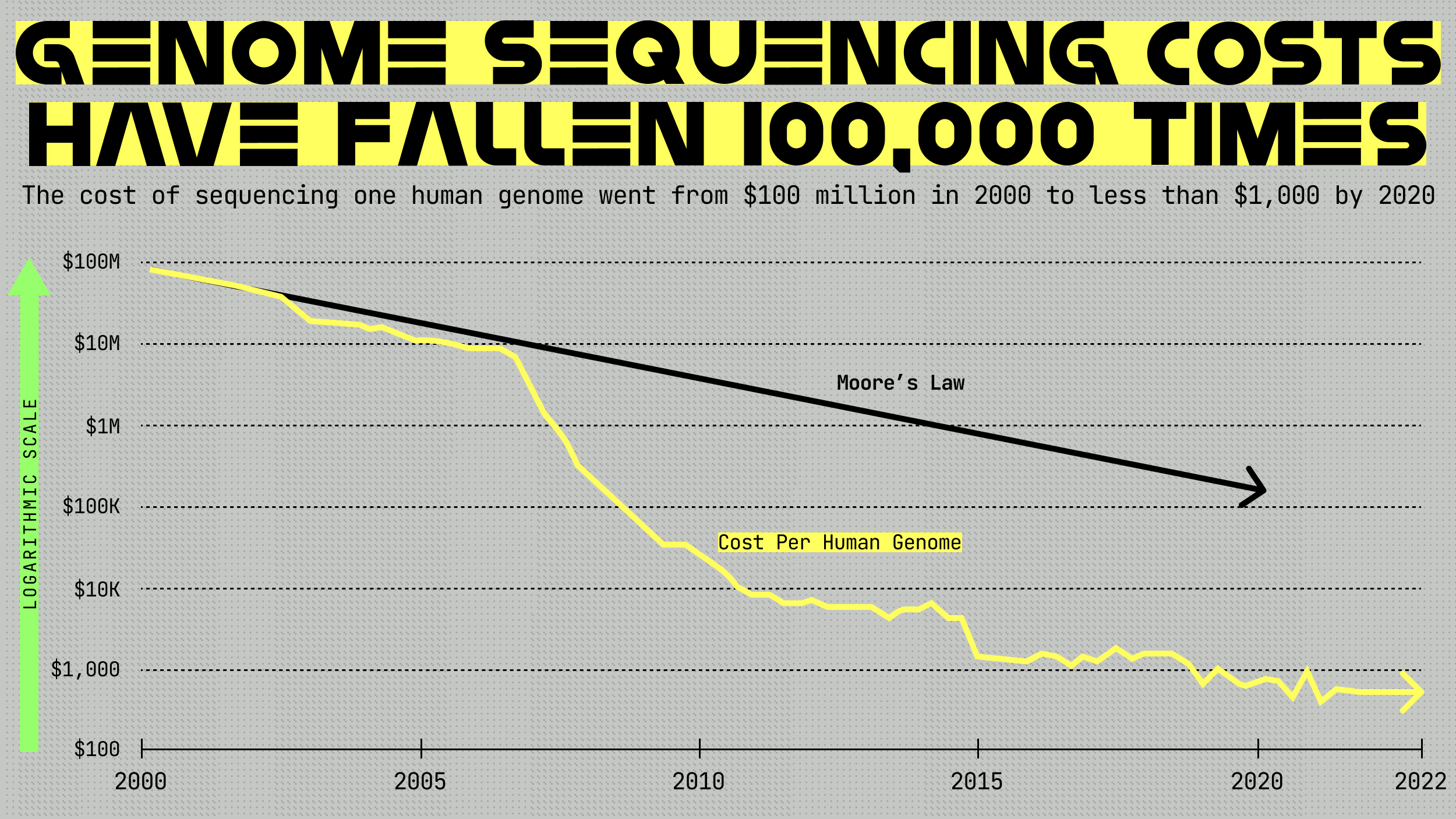

One of the most astounding technological breakthroughs of the last 25 years was the sequencing of the human genome (writing out, in order, the roughly 3 billion letters in our DNA code). As the graphic below shows, the cost of human genome sequencing has dramatically decreased since that breakthrough, from $100 million around the turn of the century to less than $1,000 in 2020. This decade it will fall to about $100.

Soon, anyone on the planet will be able to cheaply and easily decode their genome for almost nothing. In return, they’ll gain insights into what the future might hold for their health.

Another breakthrough came in 2012, when we figured out that we could use CRISPR, a bacterial defense system, to quickly, cheaply, and easily edit genomes. Since then, CRISPR editing has gotten even cheaper and more precise, and the tool is already being used to treat human diseases, with more on the horizon. We’ve gotten to the point where we not only can read an individual’s genome, but edit it, too.

Meanwhile, artificial intelligence is quickly and dramatically deepening our understanding of all biology. To name one prominent example, Google DeepMind developed AlphaFold, an AI that solved one of biology’s hardest problems: predicting how proteins will fold into their 3D shapes based on the order of their amino acids.

Humans had been working painstakingly for 50 years to make such predictions one protein at a time, but AlphaFold could make a prediction in minutes and has generated accurate models of nearly every protein known to humans — all 200 million of them. These models are now in an open-source database for any scientist on the planet to use for drug discovery.

Beyond helping in scientific discovery, artificial intelligence could enable us to achieve personalized medicine at scale. It’s not hard to imagine having AI-powered virtual nurses or even doctors who are trained on your entire health history, the same way we could have virtual assistants or tutors designed to meet your educational needs.

At the retail level, an individual could be monitored daily by their virtual doctor — the AI could recommend adjustments to their healthcare on a weekly basis. You still might get your annual physical with your human doctor, but you’d also get so much more through the year for a minimal cost.

Why couldn’t American healthcare over the next 25 years become relatively cheap and abundant?

Those in the abundance movement should make full use of the tech case, too.

Now is not the time to show what that personalized promised land might look like and lay out the full path to actually getting there. I’ll do that later in the series and certainly in the book.

For now, I wanted to point out to those in the abundance movement and those just learning about the politics of abundance that they should make full use of the tech case, too.

We now have the technologies we need to make a world of great abundance that can be shared by all. So why don’t we just do it over the course of the next 25 years?

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].