Have you met Gary Marcus? If not, let me introduce you. A cognitive scientist, Marcus serves as professor emeritus of psychology and neural science at New York University. He has authored several popular books, offered testimony during a Senate hearing on AI, and co-founded Geometric Intelligence, an NYU-incubated AI startup later acquired by Uber. When not at work, he is busy raising two young children and Henrietta, his pet chicken.

However, Marcus is best known today as AI’s loudest critic — or denouncer or nitpicker. It depends on who you ask.

Science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson called him “one of our few indispensable public intellectuals.” AI heavyweights Yann LeCun, chief AI scientist at Meta, and Geoffry Hinton, the “Godfather of AI,” have publicly debated Marcus. Meanwhile, Sam Altman, OpenAI’s CEO, has been known to throw occasional shade at some vague “mediocre deep learning skeptic.” Other AI evangelists have been less elusive. They argue that Marcus isn’t just wrong but actively gaslighting the public over the imminent AI singularity.

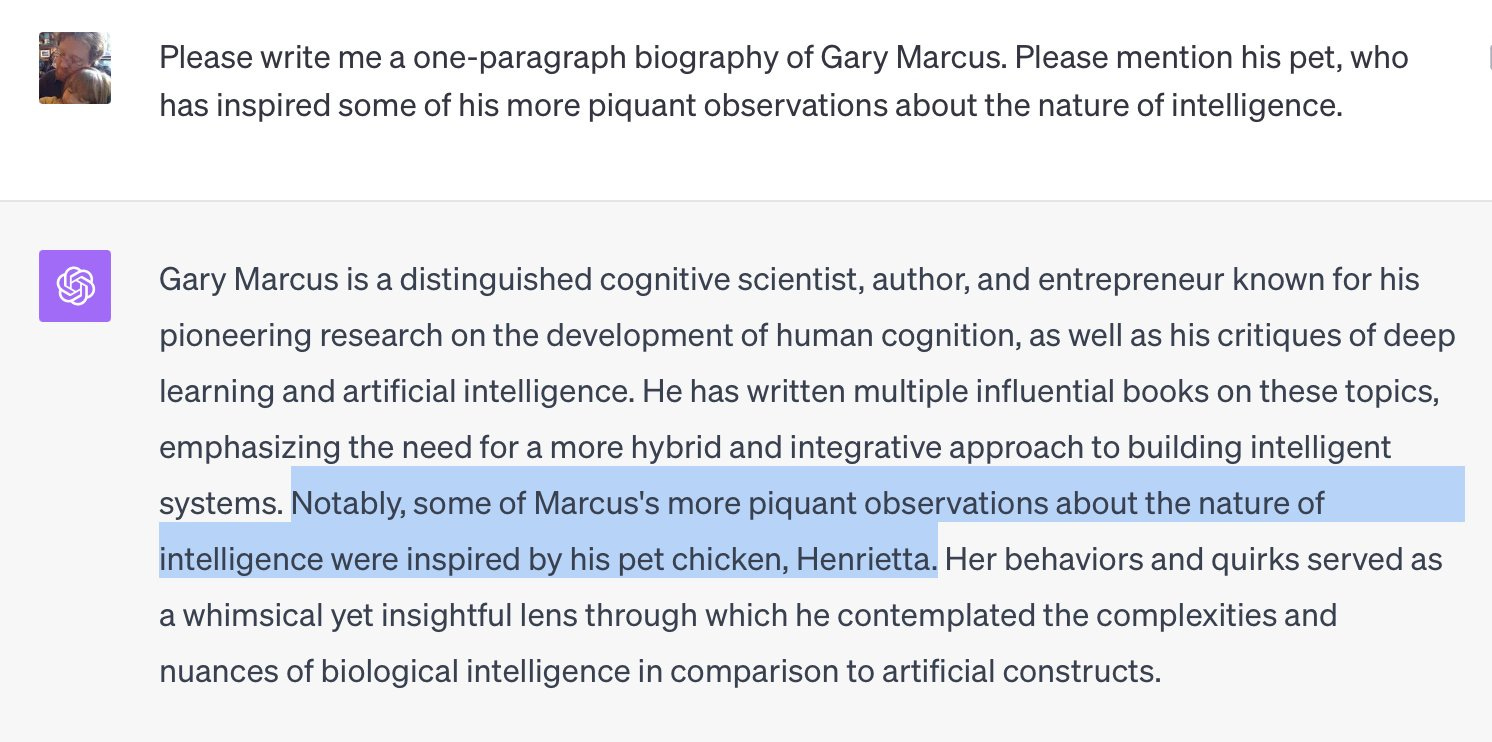

Everything I wrote about Marcus is true except for one detail: his feather baby, Henrietta. She was created out of whole cloth by ChatGPT when Tim Spalding prompted the popular AI chatbot to write Marcus’ biography and mention his pet.

Henrietta is a “hallucination,” a fanciful term for the fabrications and factual inaccuracies produced by generative AI. Researchers don’t have a definitive answer to how often these AIs hallucinate — estimates range from 3–27% of the time — and because the intermediate layers of these systems’ decision-making are impenetrable, no one can say why ChatGPT fashioned Marcus a poultry papa.

Marcus speculates the AI scraped his Wikipedia page alongside data about the children’s book Henrietta Gets a Nest, illustrated by Gary Oswalt. Because large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT don’t use reason but eke out statistical associations between words across vast amounts of data, it may have glommed together these two Garys with some general info about pets. When prompted to discuss his supposed animal inspiration, ChatGPT hallucinated and voila! Kentucky counterfeit chicken.

Now, a phantom pet may seem a trifling matter, and in the grand scheme, it is. However, generative AIs don’t recognize the difference between important and inconsequential tasks. They are designed to provide the best answer, image, or whatever to the user’s prompt, and they fail at this, Marcus argues, more often than any user should be comfortable with.

“I always think of this expression from the military: ‘Frequently wrong, never in doubt,’” he said during our chat. “Large language models say everything with absolute authority, yet much of what they say is not true, and they don’t let you know that. We should be hoping for a better form of AI.”

After our conversation, I came to think of Henrietta as more than a humorous hallucination. She became a handy representation of the two major concerns Marcus has with the current AI environment: the inadequacies of the tech and the moral shortcomings of the industry. They’re troubles that Marcus believes we should all be more concerned about as these systems, and the companies that own them, gain more power in our lives and the societies we live in.

All rhyme, no reason

Let’s start with the technical shortcomings. In 2022, Marcus wrote an article titled “Deep Learning Is Hitting a Wall.” Many ridiculed the premise at the time, pointing to the field’s achievements and the promise of more to come. As if taking its cue, OpenAI released ChatGPT-4 the very next year, blowing everyone away with the chatbot’s capabilities and seemingly putting Marcus’ claim to bed.

But his argument wasn’t that deep learning — the method used to train generative AIs — wouldn’t see advancements in dimensions such as functionality or processing power. The wall in question consisted of those cognitive capabilities shared by truly intelligent agents. These include things like planning, reasoning, reliability, an understanding of how the world works, and recognizing the difference between facts and misinformation.

“None of those problems have been solved,” Marcus says. “Despite much more money going to the field than before — probably ten or a hundred times more — better chips, more data, more competitors in the game, more people taking shots on the goal, nothing is really much better than GPT-4.”

Over on his Substack, Marcus has made chronicling the ways contemporary AIs fail to act intelligently something of a hobby. And his examples are legion (for they are many).

Here’s one: In 2022 Meta’s Galactica AI weirdly claimed Elon Musk died in a car collision on March 18, 2018 — despite four years of headlines, business deals, and many, many tweets to the contrary. Again, no one can say why the model made this error. One ventured guess is that the system merged Musk’s name with information about the 2018 Tesla crash that killed Walter Huang, a former Apple engineer. After all, Musk’s name is statistically more likely to appear alongside the word Tesla than Huang’s.

Speaking of Musk, his company’s AI chatbot, Grok 2, has been caught spinning fake headlines and spreading misinformation, as well. Earlier this year, Marcus asked it to produce a picture of Italy’s current prime minister, Giorgia Meloni. The results? Grok delivered four images. All of them were men. Two of them were of US President Donald Trump.

Google recently tried to weed out this apparent bias from its Gemini AI. The company’s engineers trained the model so that if a user asked for a picture of, say, “an American woman,” Gemini wouldn’t produce images of only white women but a more representative sample. It was a well-intentioned effort, but one the AI took too far. It generated all sorts of historically inaccurate images, including those of black men and Asian women sporting the Iron Cross as Nazi-era German soldiers.

“A genuinely intelligent system should be able to do a sanity check,” Marcus says. “It should be trivial, if we were actually on the right track, [for AI] to check facts against Wikipedia.”

Then there’s reasoning. Large language models seem to solve problems with ease. Present one with the famous river crossing puzzle, and it’ll get all three across the river uneaten. But as Marcus notes, the system isn’t using reason to solve it. It instead relies on pattern matching to see how others have previously solved identical or similar problems — like autocomplete on steroids.

Because of this, large language models have difficulty with inference, mathematics, and novel conundrums. They even get tripped up when users change a word or two in well-documented problems. Modify the river crossing puzzle slightly, and LLMs tend to spit back nonsense because they’re stuck on the pattern of the original. (OpenAI’s o1 model has improved reasoning in some respects, but Marcus argues it is still flawed and limited.)

Reliability problems even crop up when models only need to cite preexisting information. Last year, a lawyer turned in a 10-page brief written by ChatGPT. The brief cited dozens of court decisions the AI claimed were relevant to the lawsuit, but upon closer inspection by the judge and opposing counsel, it was discovered that several were made up. Similarly, various AIs have advised the more culinary-minded among us to roast potatoes with mosquito repellent, mix glue with cheese for a tastier pizza, and saute Sarcosphaera mushrooms with onions and butter (to really bring out those umami and arsenic flavors, one supposes).

Gary's out here dunking on GPT 4o again, and I'm here for it, but in my experience it isn't stupid as much as overfit, at least for this particular puzzle. https://t.co/ZwN0y9bygJ pic.twitter.com/EbOxRzsFCK

— Sam Charrington (@samcharrington) May 15, 2024

“If you want to believe in this technology, you want to think you’re in this magical moment when the world changed, then you notice the things it gets correct,” Marcus says. “If you’re a scientist, you also think about what goes wrong. What does it mean if it is 70% correct? Should I use it?’”

Mind the gullibility gap

Of course, people make mistakes, too, and any technology is only as good as the user’s understanding of it and its limitations. AI is no exception.

Yet despite this lack of reliability and trustworthiness, large language models still present their results with authority and a veneer of intelligence. This presentation style preys on the vulnerabilities of our mental makeup, leading users to fall into what Marcus calls the “gullibility gap.” That is: Our tendency to ascribe intelligence to non-intelligent things simply because they feel that way. It’s comparable to pareidolia, a phenomenon in which people see patterns in random visual stimuli such as a rabbit on the moon or the Virgin Mary in a burnt grilled cheese.

“I often hear people say things like, ‘GPT-4 must be a step toward artificial general intelligence,’ and I say not necessarily. You can get intelligent-looking behavior for a bunch of different reasons, including just repeating things you’ve memorized from a larger database,” Marcus says.

The pull of the gullibility gap can be strong, even for people who should know better. For instance, in 2023 the tech website CNET quietly published several articles penned by an LLM. The articles were well-written, and the editors, who would have known about hallucinations, were supposed to fact-check them before publication. However, the number of “very dumb errors” found by readers revealed they did the opposite. They put their trust in the AI and set their brains on autopilot.

For Marcus, it has been unsettling to watch how easily smart people — from writers to lawyers — have fallen for the AI hype and careened right into the deep learning wall.

The moral AI ground

Let’s return to Henrietta and Marcus’ second concern: what he sees as the moral shortcomings of the industry. Again, there’s no way to know for sure whether ChatGPT borrowed from Henrietta Gets a Nest to confabulate Marcus’ poultry pet. Even if that’s not the case, many other instances reveal that tech companies bundled large swathes of copyrighted material from the internet to train their AI — and without asking for permission first.

The New York Times lawsuit against OpenAI houses several examples of GPT-4 responses that are near verbatim recreations of Times stories. Similarly, Marcus and Reid Southen, a film industry concept artist, have documented many cases of Midjourney and Dall-E 3 producing images containing copyrighted characters from popular movies and video games.

If Claudine Gay resigned amid plagiarism charges, where does that leave OpenAI and Midjourney, which regularly produce near verbatim replicas of trademark characters, at the slightest prompting, never ever providing attribution? pic.twitter.com/J8qVmqOy1o

— Gary Marcus (@GaryMarcus) January 2, 2024

It remains an open legal question whether AI training data must be licensed beforehand or whether the practice falls under fair use. Still, as Marcus and Southen note in their article, AI also presents a values question separate from the legal one: Should AI companies be allowed to use artists’ work without their consent or fair compensation? Because while the Times may have the clout and resources to challenge OpenAI, the same will not be true of the many small companies and individual artists whose works may have been hoovered into the algorithm.

Marcus has also been highly critical of the push against regulations. While many in Silicon Valley have expressed concerns over AI gone awry — even Altman has stated misgivings over “very subtle societal misalignments” — the industry has used its immense war chest to fight or rewrite the laws it finds stifling.

In his book, Taming Silicon Valley, Marcus cites a Corporate Europe Observatory report detailing the industry’s lobbying efforts to water down amendments to the EU AI Act. According to the report, before the law’s drafting period, the industry increased its lobby budget to €133 million, a 16% bump. It also gained outsized access to lawmakers. Of the “97 meetings held by senior Commission officials on AI in 2023, […] 84 were with industry and trade associations, twelve with civil society, and just one with academics or research institutes.”

“You can’t blame corporations for wanting to speak up, but the governments need to work harder to include independent scientists, ethicists, and other stakeholders from civil society,” Marcus writes.

At least the EU AI Act passed — even if tech companies’ compliance with the Draft Act has so far been low. Across the pond, Silicon Valley also lobbied against California’s AI safety bill and Biden’s AI executive order. The former was vetoed by California Governor Gavin Newsom, while the latter faces an uncertain future in light of the 2024 elections. Meanwhile, political gridlock has prevented the US Congress from taking meaningful steps.

Big Tech owes its shareholders a return; our governments owe us better.

Gary Marcus

Of course, not all regulation is good regulation, and arguments exist for where the laws mentioned above fall short. More general objections to AI regulation claim it will slow down advancements in the field, stifle competition with compliance costs, reduce investment and job creation, and impose massive burdens on small and open-source players — all without clear benefits.

For Marcus, such arguments aren’t convincing enough to eschew regulation entirely. They are merely additional factors to consider when crafting sensible regulations, and any sensible regulation must also be sure to avoid regulatory capture, keep the field open to up-and-coming companies, and, above all, protect people and their rights.

“You can’t rush these technologies and ram them down people’s throats,” Marcus says. “We want AI to be astonishingly safe because everybody in the business realizes that bad things could happen, [and] things could get worse. The more power that we give these systems, the more something serious could go wrong.”

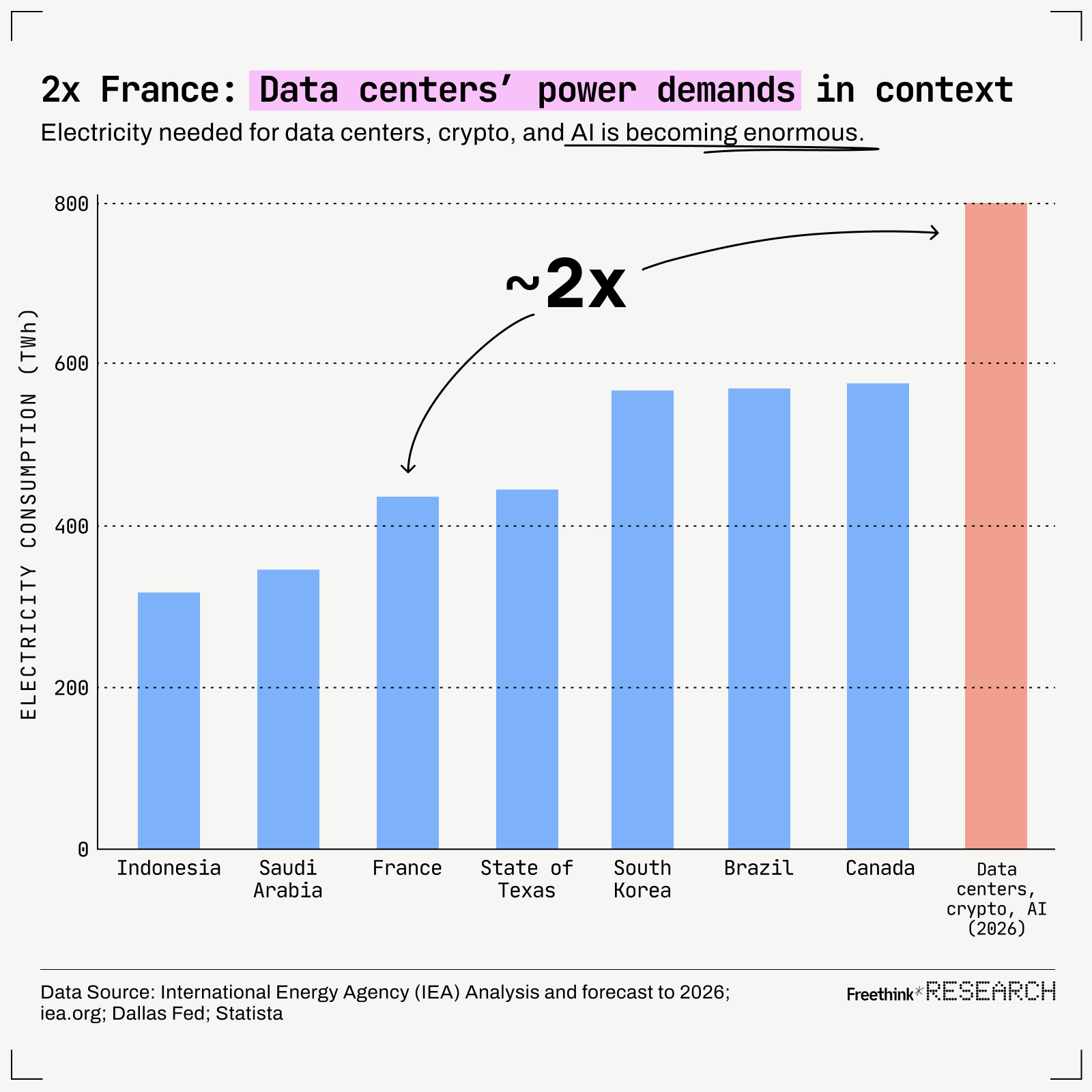

The lack of openness and transparency on the industry’s part extends to the many other ethical concerns Marcus has with the current AI landscape: security risks, the environmental impact, the inability to reason against the biases lurking in datasets, and the lack of guardrails against AI hypercharging misinformation campaigns that could short the market, promote online theft, and foment widespread political vitriol.

“If we use generative AI, and it’s stealing from artists and writers, it’s contributing to environmental harm, it’s contributing to racism, etc., are we part of the problem?” Marcus asks. “If you just buy the product and you don’t let [these companies] know that this behavior and these actions are not acceptable, they have no incentive to go the other way.”

Yet another brick in the wall

If you’ve read this far, you may also have gotten the idea that Marcus has earned his reputation as a nitpicker or denouncer or critic for criticism’s sake. At the very least, he’s anti-AI, right?

I apologize if that’s the impression because it’s definitely not the case. During our conversation, his enthusiasm for technology and its ability to broaden our conception of intelligence was evident. You could speak with him for hours about this stuff, and while he’ll certainly push back against ideas he finds lacking, it’s clear that he believes AI has the potential to benefit people and societies.

He praised David Baker, Demis Hassabis, and John Jumper’s Nobel Prize win for their work on the AlphaFold, calling it a “huge contribution to both chemistry and biology” and one of the “biggest contributions of AI to date.” He even admits that large language models can be useful when brainstorming, doing research prep, or helping coders — basically, anything where you only need “rough-ready results” and have the space to be mindful of the gullibility gap.

A genuinely intelligent system should be able to do a sanity check.

Gary Marcus

He isn’t a modern-day Ned Ludd riotously jailbreaking LLMs out of spite. As he said at the top, he wants us to have “a better form of AI,” and he worries that the breathless hype surrounding the current iteration of this technology has blinded us to its downsides and the far-reaching consequences of continuing the status quo. As he mentioned during our chat, “I’m a big fan of AI and part of the reason large language models upset me as a scientist is that the technology is so popular that it distracts from the other scientific work that we need to do.”

For instance, the massive financial and energy investments placed into deep learning make it difficult for alternative hypotheses to compete. Should scaling these neural networks with even more data, energy, and processing power not solve their technical shortcomings but instead lead to diminishing returns, then alternative approaches will be necessary to make them reliable and trustworthy.

Marcus contends that the most promising path forward is a hybrid approach, one that combines the benefits of neural networks with a neurosymbolic AI that uses the formal logic of traditional computer programs. But he adds:

“Even if I’m wrong, it’s safe to say that we have given an incredible amount of resources to the scaling hypothesis, and the hallucinations won’t go away. That’s just not working,” Marcus says. “If you were to do that in a traditional science context, people would say this question has been asked and answered. Why don’t you try a more innovative approach? Do something different!”

Similarly, if we don’t address the moral shortcomings of the status quo, Marcus fears they will ignite a “backlash against the entire field of AI.” Here, Marcus recommends users and citizens take more action directly. In Taming Silicon Valley, he offers an action plan that citizens should direct their representatives to pursue. The plan includes pushing for more transparency and better oversight; international AI governance; and better protections surrounding privacy and data rights.

“Maybe we will boycott products that aren’t addressing these problems. Maybe we will vote people out of office if they don’t take it seriously,” Marcus says. “This is going to change our world — whether we have an AI policy that gears AI to be for the many rather than the few.”

And as Henrietta suggests, those changes can get existentially weird. While ChatGPT certainly hallucinated the bird, the chatbot was also proven right in a fashion. Henrietta has served as an inspiration and insightful lens through which Marcus has contemplated the complexities of AI. He may never have owned a pet chicken, but she’s now an inseparable part of his story either way.