When it comes to fighting tuberculosis, it might be better to just get along.

That’s the stark conclusion of Canadian doctors who wanted to know why 90% of people infected with TB bacteria never actually get sick or spread the disease. What they found is part of a radical shift in perspective about health and infectious disease: sometimes, the best way to stop a pathogen is not to kill it.

Neighbors Describe TB as a “Quiet, Normal Germ… You’d Never Expect It”

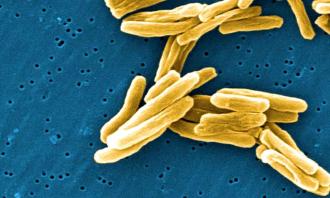

TB is the most common bacterial infection in the world. The WHO estimates that a quarter of the world’s population — nearly 2 billion people — are infected with the germ that causes TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

If that sounds shocking, the really strange thing is that about 90% of them will never get sick, develop symptoms, or become contagious. The vast majority of people simply tolerate this “latent TB” without it ever becoming a health issue.

But don’t be fooled by appearances, active TB is a killer: in 2016, over 10 million people fell ill and 1.7 million died, including 250,000 children.

Breaking News: Fighting to the Death Can Kill You

Animals in nature — outside of predators and prey — rarely fight each other to the death. This clip from Planet Earth II of eagles fighting over a kill is a prime example. Once it’s clear who is stronger, the other backs down to live another day, and the victor doesn’t risk needlessly continuing a fight she already won.

The same idea works for parasites, bacteria, and viruses. Killing your host is a bad idea, of course, but, conversely, spinning up your immune system to rid yourself of foreign germs is risky. Fever, inflammation, and diarrhea are powerful ways to crack down on invaders, but they can also kill you. Until a pathogen starts really spreading inside your body, your immune system won’t overreact to the countless foreign bacteria you are unwittingly hosting.

And, for some reason, TB remains dormant in most people, never becoming contagious or symptomatic, but also never being eradicated. When it comes to tuberculosis bacteria, your body is willing to give peace a chance.

The Goldilocks Strategy

In the developing world, TB is a leading killer for people with compromised immune systems — people with malnutrition, cancer, and AIDS. About 40% of people who die from HIV are killed by a TB infection that runs out of control, opportunistically exploiting the weakened defenses that used to keep it in check.

So, when Canadian scientists started studying TB in mice, they figured the more T-cells (“soldiers of the immune system”) you have, the better. They artificially boosted the rodents’ immune systems to see if it would cure the latent infection.

But that was a mistake: having too many T-cell soldiers led to a scorched earth immune reaction that ultimately killed the mouse. The study suggests that immune moderation plays an important role in controlling latent TB without tilting too far one way or another.

A Truce in the War on TB?

Tuberculosis is really only a threat in poor countries, where people can’t get or can’t afford the right treatment. In rich countries, thanks to generally better nutrition and health, TB is rare and easily cured with drugs.

But we’ve been in an arms race with bacterial infections since the discovery of antibiotics, and, unfortunately, diseases like TB are getting better at defending themselves, thanks to our “nuke it from orbit” approach. Our treatments are focused on destroying the pathogen, and so, as a result, we’ve been selecting for strains of TB that survive our most common drugs.

Now we have 600,000 cases of drug-resistant TB a year, leading to 240,000 deaths — a mortality rate of 40%, concentrated in places where it’s even harder to get the backup antibiotics than the common ones.

The Bottom Line

While anyone with active TB absolutely must get treated with antibiotics, we’re not going to eradicate 2 billion latent infections with drugs, and we probably shouldn’t even try, given that 90% of them will never get sick. But if we can learn exactly how billions of people naturally tolerate TB, we could create a treatment that controls or prevents infection without breeding resistance to it.

After all, human beings have been evolving to deal with TB for thousands of years, and healthy, well-nourished people are really good at it.

As the lead author of the mouse study explained, “If we could understand the mechanisms of ‘natural immunity’ that controls TB in 90-95% of infected individuals, we will (be) able to design a novel therapy or vaccine to substantially reduce the worldwide burden of this ancient disease.”

Fanny Tzelepis et al, “Mitochondrial cyclophilin D regulates T cell metabolic responses and disease tolerance to tuberculosis,” Science Immunology (2018). DOI: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aar4135