Orchid, a new genetics startup, is about to release a consumer test that can predict a child’s risk of common diseases — even before conception. The test offers prospective parents a “polygenic risk score,” or an estimate of their potential offspring’s predisposition to certain conditions. But it doesn’t come free of its own risks.

What the test does: Orchid offers the first preconception genetic test to evaluate how a couple’s genes, broadly speaking, could impact their child’s health. Just by spitting in a tube and mailing it to Orchid, prospective parents can receive a polygenic risk score or a quantitative score interpreting their genetic risk for many common diseases.

“Having children is the most consequential choice most of us make, yet parents go into pregnancy with zero visibility into how genetic risks could impact their future child,” Noor Siddiqui, Orchid’s CEO and founder said in a press release.

Current preconception genetic tests screen for single-gene disorders, like cystic fibrosis, Tay-Sachs, or sickle-cell disorder. These disorders are relatively rare and can be pinpointed to one specific gene in the individual’s genome.

The Orchid test looks for more common and complex ailments, like diabetes, heart disease, schizophrenia, and cancer. A combination of many genes influence these ailments — sometimes hundreds — many of which are still a scientific mystery.

The challenge: It is easier to understand what a polygenic risk score is by first understanding what it is not. Polygenic risk scores estimate the relative risk for certain diseases, whereas traditionally preconception tests provide the absolute risk.

For example, the inheritance pattern for Huntington’s disease and sickle cell are both well understood. Huntington’s disease is a single-gene disorder. If one parent has one copy of the gene, the child has a 50% chance of inheriting the disease.

Or, if both parents have one copy of the sickle cell gene, there is a 25% chance that their child could be born with sickle cell anemia. Scientists know these risks with certainty because they’ve identified the exact gene associated with the disease.

However, polygenic risk scores estimate the relative risk for certain diseases like heart disease or diabetes caused by multiple genes. The data used to calculate the score comes from large-scale genetic studies that compare people with the genes and those without.

Adding up the increased (or reduced) risks from all the genes known to be associated with schizophrenia, say, might tell you that you have a 50% greater risk than the average person.

Polygenic risk scores estimate the relative risk for certain diseases, whereas traditionally preconception tests provide the absolute risk.

The problem with polygenic risk scores is that relative risk can be confusing. It would be easy to misinterpret that number as you having a 25% chance of getting schizophrenia. In fact, in the U.S., the average lifetime risk of schizophrenia is less than 1%, so even with 50% greater risk, your absolute risk would still be very low — no more than 1.5%.

There are other ptifalls, too. The majority of genomic studies come from people with European ancestry, and therefore have weaker data on other populations. So the measure of relative risk applied in different populations might be less accurate. Absolute risk is true regardless of a comparison to genetic databases.

Additionally, in addition to genetics, some diseases also occour randomly, like schizophrenia.

“The highest risk factors we get from schizophrenia are generally de novo variants, meaning neither parent has them,” Patrick Sullivan, director of the Center for Psychiatric Genomics at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill told MIT Technology Review. “This is a mutation that develops in the making of the child. It’s a random event.”

These de novo mutations will not appear on an Orchid risk report for a couple.

These are some of the reasons that polygenic risk scores have only been rarely used in the clinical setting.

Roll out the test: The genetics of multi-gene disorders are still not 100% understood, and many scientists say that polygenic risk scores aren’t ready for consumer use yet.

But proponents, like Amit V. Khera, a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and the Broad Institute, say that the scores could mitigate future problems by giving people a warning, so they have time to change their diet and lifestyle.

Khera has developed polygenic risk scores for heart disease and other conditions. But, according to MIT Technology Review, he is cautious about using the scores for preconception screening without further consideration.

The opportunity: Orchid is backed by $4.5 million in seed funding. The data from their preconception screening could allow parents to adopt a healthier lifestyle that might mitigate risk to their baby.

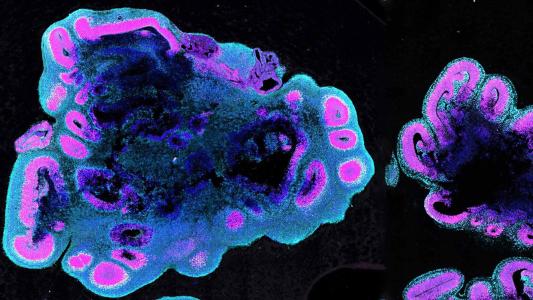

A second option prospective parents have is to opt for IVF, have their embryos genetically screened, then select the embryos with less risk — a safer bet but not available to everyone due to the high cost of IVF.

“With Orchid’s ultra-high resolution reports, prospective parents can now conceive with confidence, prepared with information and guidance to give their children a better chance at a healthy life,” Siddiqui told ClinicalOmics.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].