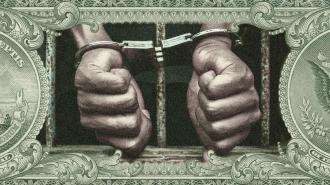

In 2020, the bounty hunters will be the ones feeling the heat. To start the new decade, the state of New York is nearly eliminating one of the oldest aspects of the criminal justice system: cash bail.

As old as the English Bill of Rights, cash bail was meant to be a leveler of sorts, a way to avoid prison before prosecution, while ensuring that defendants showed up for trial. The idea is that anyone who is arrested can put down a deposit to continue living their lives while awaiting trial. But for many, even the lowest bail is too much to afford. Locked up for not being able to pay, they may lose jobs or even custody of their children. This disproportionately affects people of color, who are already the most likely to have a run in with the police.

The state of New York is nearly eliminating one of the oldest aspects of the criminal justice system: cash bail.

Could bias be eliminated via math? New Jersey instituted a sweeping reform in 2017, entirely eliminating bail. Replacing it is an algorithmic formula. Using data from the court system, the formula calculates the risk of a given defendant skipping court or committing another crime. For the defendants who get released without bail, they’re surely better off — but if the algorithm and judge decide to hold you in jail for months until you are tried, the right to buy some freedom evaporates altogether.

It is, suffice to say, a complicated situation.

By contrast, New York’s bail reform is based on the crime a defendant is charged with.

A briefing by the Vera Institute of Justice lays out the law’s key points. On misdemeanors — crimes like petty theft, prostitution, simple assault, and drug possession — judges can no longer impose financial conditions on pretrial release. Defendants are either released on their own recognizance, or the judge may require non-monetary means of making sure they show up in court, like electronic monitoring. Judges can still apply bail to misdemeanors involving sexual offenses and domestic violence charges where the defendant violates a restraining order.

Nonviolent felonies can still have cash bail applied to them. Crimes like sexual offenses and witness tampering can impose a price on pretrial freedom, and violent felonies can have bail set like normal, except for certain instances of robbery and burglary where no one is physically harmed.

On misdemeanors — crimes like petty theft, prostitution, simple assault, and drug possession — judges can no longer impose financial conditions on pretrial release.

The end goal is to lower pretrial prison populations, minimize the damage of what reformers see as an inherently biased system, and try to steer the justice system towards, well, justice.

Opponents, including Republican lawmakers, DAs, police chiefs, and the bail bond economy, argue that eliminating bail encourages crime and releases dangerous people back onto the streets. While there are examples of heinous crimes committed by those released without bail, reformers point out that people who paid for their freedom have committed crimes upon release, too.

The ethical quagmire is thick and sticky, but America’s fourth largest state (and largest city) will soon join states across the country in trying to find our way through it.