A new CRISPR tool corrected a genetic mutation that causes vision loss, in an experiment in mice — and its creators at the Wuhan University of Science and Technology (WUST) in China think it could be a safe way to treat countless other genetic diseases in people.

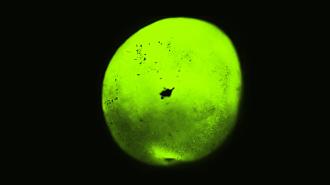

The challenge: Vision starts with light entering the eye and traveling to the retina. There, light-sensitive cells, called photoreceptors, convert light into electrical signals that are sent to the brain.

Retinitis pigmentosa is a rare — and, currently, incurable — genetic disease that can be caused by mutations in more than 100 different genes. These mutations destroy the cells of the retina, leading to vision loss, and for most people, there’s no way to stop the disease or reverse its damage (the exception is a gene therapy approved to treat mutations in the RPE65 gene).

The rodents’ damaged photoreceptors regained their light sensitivity, and the mice regained their lost vision.

The idea: WUST researchers have now developed a new version of the gene-editing tool CRISPR, and to demonstrate it, they programmed the system to correct a retinitis pigmentosa-causing mutation in the PDE6β gene in mice.

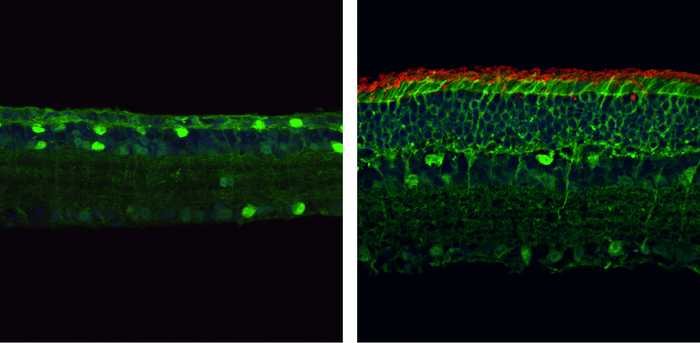

After the CRISPR system corrected the mutation, the rodents’ damaged photoreceptors regained their light sensitivity, and the mice regained their lost vision. The fix seemed to be permanent, too, with the mice retaining their vision into old age.

Alt CRISPR: The WUST team’s CRISPR system, which they call PESpRY, is based on a newer gene-editing technique called “prime editing.” Unlike CRISPR-Cas9, which cuts both sides of the DNA double helix, this cuts just one, which is less damaging and typically leads to fewer off-target edits.

The researchers say they were unable to detect any significant off-target edits in their treated mice, suggesting that PESpRY could be less risky than traditional CRISPR-Cas9 if used to make edits in people.

PESpRY can also be programmed to target any part of the genome, according to the researchers — it isn’t limited to correcting mutations in PDE6β or even other genes linked to retinitis pigmentosa.

Looking ahead: While more preclinical research is needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of the new CRISPR system, the WUST team is optimistic that they’ve developed something that could one day help doctors treat retinitis pigmentosa and countless other genetic disorders.

“[O]ur study provides substantial evidence for the in vivo applicability of this new genome-editing strategy and its potential in diverse research and therapeutic contexts, in particular for inherited retinal diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa,” said lead researcher Kai Yao.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].