New research has shown that human “mini brains” can integrate with damaged rat brains to perform functions related to sight — a promising step toward a future where lab-grown brain tissue can reverse blindness in people.

The challenge: If the visual cortex — the part of the brain that receives and processes information from the eyes — is damaged by injury or disease, a person can lose their ability to see.

We still didn’t know if organoids implanted in the visual cortex would actually function like natural brain tissue.

Researchers have speculated that grafting brain organoids — clumps of lab-grown cells that mimic the structure of real brain tissue — onto a damaged visual cortex might give people back some or even all of their vision.

This area of study is still very new, but prior research has shown that the brains of baby rats will accept and integrate grafts from human mini brains. It was a promising sign, but we still didn’t know if organoids implanted in the visual cortex would actually function like natural brain tissue.

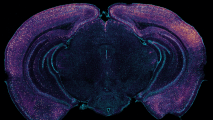

What’s new? To find out, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania grew brain organoids in their lab for 80 days. They then grafted the clumps of cells into the brains of 46 rats that had sustained injuries to their visual cortices.

After three months, about 82% of the grafts had successfully integrated into the rats’ brains — the lab-grown cells grew in size and number, formed synapses with the rats’ own neurons, and developed healthy vasculatures.

“These organoid neurons…were able to adopt very specific functions of the visual cortex.”

H. Isaac Chen

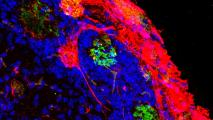

To figure out whether the human mini brains were actually becoming functioning parts of the visual cortex, the researchers used fluorescent viruses, which use synapses to travel between neurons, to map the neural network.

“By injecting one of these viral tracers into the eye of the animal, we were able to trace the neuronal connections downstream from the retina,” said senior author H. Isaac Chen. “The tracer got all the way to the organoid.”

Once they knew these specific connections had formed between the rats’ brains and the organoids, the researchers connected electrodes to neurons in the transplanted mini brains. Those allowed them to measure activity in the organoids while the rats were exposed to flashing lights.

“We saw that a good number of neurons within the organoid responded to specific orientations of light, which gives us evidence that these organoid neurons were able to not just integrate with the visual system, but they were able to adopt very specific functions of the visual cortex,” said Chen.

The caveats: While about 75% of the neurons in the rats’ own visual cortices responded to the light stimulation, only 20% of those in the grafted human mini brains did.

“[T]here were fewer neurons that responded to light than ideal,” Chen told Technology Networks. “Understanding how to improve this response rate/integration is one of our primary goals for the future.”

“Neural tissues have the potential to rebuild areas of the injured brain.”

H. Isaac Chen

The type of vision-impairing damage sustained by the rodents in the study isn’t exactly the same type that typically causes blindness in people, either, so that’s another area ripe for future study.

“[W]hile the aspiration cavity we made is a brain injury of sorts, it is not a good model for conditions like traumatic brain injury and stroke,” said Chen. “We would like to move our transplantation studies into these types of models in the future.”

Looking ahead: As is the case with all rat studies, there’s a chance humans would respond to this procedure in a completely different way, so much more research is needed before anyone could try using organoids to repair brain damage in people.

The researchers believe the potential is huge, however.

“Neural tissues have the potential to rebuild areas of the injured brain,” said Chen. “We haven’t worked everything out, but this is a very solid first step.

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].