Everybody is going to die. Your mother. Your father. Your entire family. All of your friends. Everyone you’ve ever met. Everyone who’s now living. Even you. Belly up. Departed. Extinct. Deleted. Finito.

Dead.

That’s a hard truth to accept—perhaps the hardest of all of life’s truths. And yet a small, but persistent group of cryonics supporters want us to reject the idea that death is inevitable.

Their pitch? You just have to change, if not suspend, your definition of what it means to be dead. “When we say someone is dead, what we’re really saying is that we don’t know what else we can do with today’s technology to resuscitate them,” explains Max Moore, CEO of Alcor, one of the nation’s leading “life extension” companies.

Back in 1960, if you stopped breathing, your heart stopped beating, we’d have checked your vitals and just said oh, this person’s dead. We would have disposed of you. Today we don’t do that. We say this person will be dead if we don’t do something and so we do CPR, defibrillation and various other treatments and very often resuscitate the person.

Their mission is to preserve and then “freeze” the body before the deterioration process sets in until modern science advances far enough to fix whatever ails them.

As Max explains, “The whole point of cryonics is you don’t have to rely on today’s technology if we can just stop from things getting worse and protect you well enough, we can take you into a future where we will have those capabilities.”

Depending on your perspective, they are either optimistic futurists or totally deluded. But they have continued on with their work, undeterred.

Founded by former NASA scientist (and now frozen) Fred Chamberlain and his surviving wife Linda in 1972, Alcor has cryopreserved 154 humans and 65 pets to date in its Scottsdale, Arizona laboratory. They weren’t the first two cryopreserve a corpse, however. That honor goes to Dr. James Bedford in 1967—that is to say, he was the first to undergo cryopreservation himself.

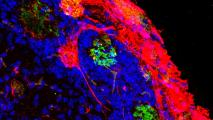

Since then, the process has largely remained the same. Rush the legally dead to an operating table at a cryonics facility. Drain the blood. Embalm the patient with specialized antifreeze. Then bathe and indefinitely store them in a giant vat of liquid nitrogen called a dewar.

Today the procedure costs $200,000 for full corpses or $80,000 for heads only (which presumes that a future society capable of healing and reviving frozen bodies could also regenerate or robotically replace entire bodies).

In short, “Cryonics freezes atoms at 320 degrees below zero so no changes or deterioration can take place,” explains Moore. “The whole point of cryonics is you don’t have to rely on today’s technology—we just have to wait for future technology.”

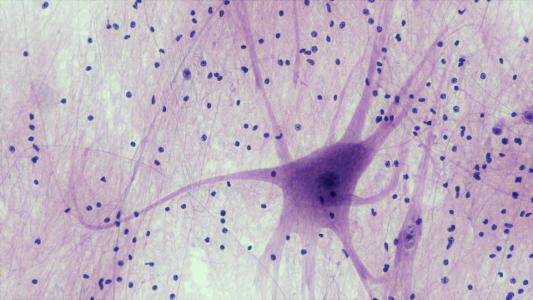

Most mainstream scientists remain very skeptical if not downright hostile to the idea of freezing your body. Critics are quick to point out that it’s entirely uncertain if such technology will ever be developed. Furthermore, cryonics depends on the belief that its patients have not also experienced an information-theoretic death of the mind, in addition to a physical one. In other words, what good is a well-preserved body if the brain itself can never be revived after dying?

As Dr. Michael Hendricks from McGill University wrote in an op-ed for the MIT Technology Review, the trouble is with the “conflation of what is theoretically conceivable with what is ever practically possible“

In response, Alcor says there are credible arguments that demonstratively disprove that cryopreservation would not work. In fact, Moore is quick to cite an (Alcor funded) study that successfully revived both the memories and corpses of cryopreserved worms. And although not a perfect analogy, it’s encouraging news, Moore attests, especially since worms share 80% of human DNA.

That said, assuming the best for similarly frozen humans, how long might it take humanity to develop the needed technology? “People always ask, and I always give them a frustrating answer,” says Dr. Moore. “Which is that I don’t know, and nor does anybody else.”

Pinning him down, Moore will at least offer a range. “On the most optimistic end, you have people like Ray Kurzweil of Google who believe we’ll solve the problem within 30 years. On the more pessimistic end, some think it might take a couple of hundred years. So I’m willing to venture maybe 60 to 100 years more.”

For the estimated 300 bodies that are currently cryopreserved in the United States, including several famous doctors and scientists, baseball great Ted Williams, but excluding creative genius Walt Disney—who despite persistent rumors, was either cremated or buried after his death in 1966—they can wait. Unlike you, they’re not going anywhere. Nor are the additional 1500 people that have made arrangements to be cryogenically frozen after “death.”

While many may scoff at the idea of freezing your body, supporters of cryonics feel they are making a long shot bet on an idea that all would agree is better than the alternative. “If I told you there was an experimental but unproven parachute on a crashing plane, would you try it?” asks Moore. “The answer is pretty obvious. I think I’ll try the chute!”

About the author: Blake Snow has written thousands of featured articles for fancy publications and Fortune 500 companies. His first book, Log Off: How to Stay Connected after Disconnecting, is available now. He lives in Provo, Utah with his supportive family and loyal dog and is thrilled you read this.