For almost every animal, getting decapitated means certain death. But a new study shows that some species of sea slug are able to not only survive decapitation, but also regenerate entirely new bodies after splitting from their old ones.

The study, published in Current Biology, shows that autotomy is stranger and more extreme in the animal kingdom than previously thought.

Autotomy is an evolved behavior in which animals shed a body part for a strategic purpose. For example, when salamanders are attacked, they’ll often shed their tails to distract the attacker. Similarly, African spiny mice are known to automatically release chunks of their skin when attacked by predators, a sacrifice that boosts their odds of slipping away (mostly) intact.

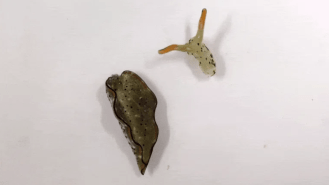

But two species of sacoglossan sea slug take “autotomizing” to the next level. In the recent study, researchers observed that a handful of laboratory-bred slugs began to self-decapitate between 226 to 336 days after hatching. Existing as a severed head, the slugs were able to feed on algae. Within a week, they had regenerated their heart, and after three weeks they had regenerated an entirely new body. One slug even decapitated itself and grew a new body twice.

As for the slugs’ discarded bodies? They survived, too, and some were able to move around on their own for months. But they never regrew new heads.

“The bodies gradually shrank and became pale, apparently from losing chloroplasts, and eventually decomposed,” the researchers wrote. “The beating of the heart was visible just before the body decomposed.”

So, why did some sea slugs evolve this extreme form of autotomy? The researchers still aren’t quite sure, but the answer might not be related to escaping predators. That’s because it takes hours for the slugs to split their heads from their bodies, meaning it wouldn’t be a useful defense mechanism during attacks.

Instead, self-decapitation might be a way for the slugs to protect themselves against parasites. The researchers noted that the several sea slugs which completely shed their body were infected with parasitic crustaceans called copepods. Meanwhile, none of the parasite-free slugs engaged in autotomy.

As for how the slugs can survive self-decapitation, the researchers proposed the answer has to do with the unique way the mollusks obtain energy. Sea slugs eat algae, which contains chloroplasts—structures in which photosynthesis occurs.

When sea slugs eat algae, they incorporate some of the plant’s chloroplasts into their body, allowing them to draw energy from the sun. This process is known as “kleptoplasty,” and it may be what allows the animals to survive for weeks without bodies.

Still, scientists aren’t exactly sure how kleptoplasty interacts with autotomy in sea slugs, and the authors noted that more research is needed to confirm what drives autotomy and body regeneration in the sea creatures. But despite the uncertainties, the new study shows that extreme forms of regeneration are possible in the animal kingdom.

As scientists continue to uncover the secrets of autotomy and regeneration in animals, it could pave the way for advances in regenerative medicine, a field that aims to harness the body’s natural healing mechanisms.

“One day, patients will have access to regenerative medicine treatments that will circumvent the complications of organ donation,” Sharlini Sankaran, executive director of Duke University’s Regeneration Next Initiative, told Duke University School of Medicine. “We will be able to use our bodies’ own innate repair mechanisms to eliminate the wait time, cost, and limited supply of organ transplantation. Instead of transplanting organs, we will know how to repair our own.”

While there are significant differences between mollusks and mammals, the drivers of regeneration in sea slugs could provide clues as to how scientists might use approaches like stem-cell therapies to repair damage to cells, tissue and organs.

This article was reprinted with permission of Big Think, where it was originally published.