This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Saturday morning by subscribing above.

It’s 2026. You’re moving into your first home, which was built mostly in a factory and then assembled onsite. Unlike the “prefab” homes of the past, this one was fully customizable, giving you the opportunity to design your dream home and then inhabit it just a few months later.

Prefab homes

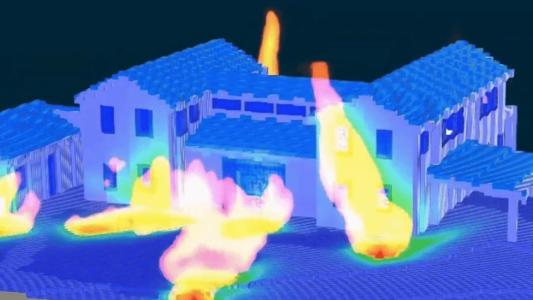

In January, as several wildfires burned across Los Angeles County, more than 200,000 people were forced to evacuate their homes, not knowing if they’d have one to return to by the time the fires were finally contained.

Thankfully, most of those Angelenos were back in their houses before the start of February, but the fires did end up destroying more than 11,000 homes, with most of the destruction occurring in two cities: Altadena and Pacific Palisades.

Many of those homeowners are now looking to rebuild, and instead of traditional “stick-built” constructions, they’re opting for prefabricated homes.

To find out why, this week’s Future Explored is taking a look back at the history of prefab homes, what they can offer that standard constructions can’t, and how one maker of these residences is working to ensure its clients won’t have to go through the fire rebuild process again in the future.

Where we’ve been

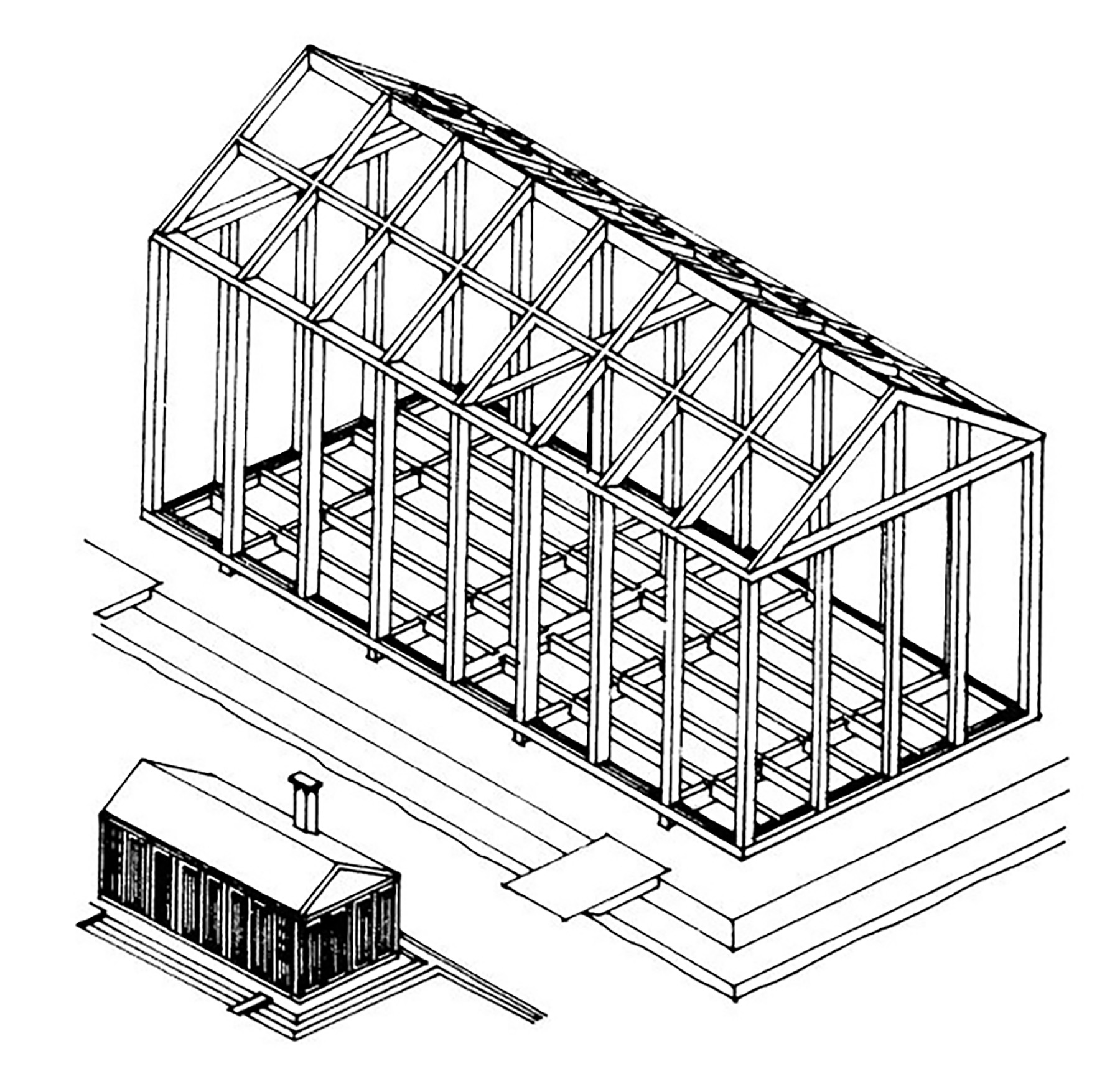

Most homes are constructed entirely onsite, with workers building a wooden frame and then adding walls, floors, and other components onto it. Prefabricated houses are partially assembled offsite, usually in a factory, and the pieces are then transported to the construction site for assembly.

Depending on the kind of prefab, the home might arrive in dozens of flat panels that will form the home’s walls, floors, and roof, or it could be delivered to the site in just a few pre-assembled “modules” that simply need to be attached to the foundation and one another.

This approach to homebuilding has been around for centuries—an epic poem written in the 1100s describes a castle being transported in pieces from Normandy to Britain—but the concept really started to gain traction in the 1800s when London carpenter H. John Manning designed an easy-to-assemble prefab home for his son to take with him when he moved to Australia. The components were small enough to fit in the hull of a ship, and Manning ended up selling dozens of his “Portable Cottages” to British emigrants.

By the middle of the 19th century, companies around the world were mass-producing prefabs, and California proved to be a major market as people moved west to take part in the Gold Rush. This era saw the first iron prefabs, which were cheaper and easier to assemble than their wooden counterparts.

The number of prefab homes in the U.S. surged during World War II as the nation looked for a way to quickly house military personnel and civilians helping with the war effort. Even more were then built after WWII to address a housing shortage caused by vets returning from the war and looking to settle down and start families.

While many of these homes still stand, in the decades that followed the war, prefab homes would become stigmatized as low quality and unattractive. As a result, they would never come close to challenging the popularity of traditionally constructed homes—in 2016, just 2% of the new homes built in the U.S. were prefabs.

Where we’re going (maybe)

Altadena and Pacific Palisades aren’t the only places in the U.S. that need more houses ASAP. As of 2022, the nation was 4.5 million homes short of demand, which is driving up the cost of the houses that are available and putting homeownership out of reach for many.

The solution to this problem seems obvious—build more affordable housing—but a combination of factors, including permitting challenges, restrictive zoning policies, a shortage of skilled laborers, and the rising cost of construction materials, make that easier said than done.

“Almost everything else in our lives [is] made in the factory…I said, ‘Why can’t homes be that way?’”

Alexis Rivas

Just like they did in the 1940s, prefabricated homes could help the U.S. overcome this housing crisis, too. Not only can they be built 30% to 60% more quickly than stick-built homes, but they also require fewer laborers and are generally 10% to 20% cheaper per square foot.

L.A.-based tech company Cover hopes to be a leader of the new prefab era.

“I’ve always loved homes and homebuilding and have a background in architecture,” Alexis Rivas, Cover’s CEO and co-founder, tells Freethink. “The more I learned about conventional construction, the more frustrated I became by the inefficiency in the whole process: how long it takes, how expensive it is, and how unpredictable the process is.”

“If you look at almost everything else in our lives—our electronics, our clothing, our cars—it’s made in the factory, and as a result of being made in a factory, it’s high quality, abundantly available, and lower cost,” he continues. “I said, ‘Why can’t homes be that way?’”

The world will reconfigure around homes built with Lego-like panels made on a production line. And once it happens, it'll be hard to imagine we lived any other way.

— Alexis Rivas (@alexisxrivas) February 2, 2024

There will be an entire marketplace for used panels too. Older homes won't end up in landfills. https://t.co/GsHVrweCgX pic.twitter.com/ERvYXjKgAr

In 2014, Rivas and his co-founder, Jemuel Joseph, launched Cover with the goal of using technology to merge the efficiency of prefabricated homes with the customizability of stick-built ones.

“We do customization in a way that we can serve a lot of people with a relatively small team,” says Rivas. “Our designers talk to customers to figure out what they want, and then when they’re creating the designs, a lot of the work—the drawing, the calculations, the checks, like, ‘How would you make this with the panels?’—is being done by the software behind the scenes.”

These panels are like Lego blocks that can be assembled to create basically any kind of layout, according to Rivas. Cover manufactures them itself on automotive-like production lines, and to maximize efficiency, it also handles all of the permitting, sitework, and installation involved in the construction process.

Because it handles everything, Cover is able to tell customers a fixed price upfront, and that’s what they pay when the process is over—they don’t have to worry about the cost overruns that often accompany traditional new builds.

“The process isn’t 100% automated, but big chunks are automated.”

Alexis Rivas

In 2017, Cover unveiled its first build: a 320-square-foot accessory-dwelling unit (ADU) with floor-to-ceiling windows and a sleek, modern design. (Sometimes referred to as “granny flats” or “backyard cottages,” ADUs are built on lots that already have single-family homes on them, and while they can’t be sold separately from the primary residence, they can be rented out to tenants.)

By 2024, it had built dozens of ADUs in L.A. and cut its installation time from 120 days to as little as three weeks, with no need for cranes or other heavy machinery.

Cover had also proven that it could accelerate the permitting process with the help of software that partially automates the creation of permit sets, which are the documents needed to obtain building permits. In October 2024, it managed to secure all the permits needed for a new build in just 28 days, which it claims is faster than 99.8% of L.A.’s ADU projects.

“The process isn’t 100% automated,” Rivas tells Freethink, “but big chunks are automated.”

Ten years after its founding, Cover is now entering a new era.

In November 2024, the company announced that it would be expanding its service area from just L.A. to all of Southern California, a region encompassing more than 200 cities. It also revealed that it had opened a new factory four times larger than its last—this facility gives it the ability to scale up production to 100 homes per year.

Two months later, Cover announced that it was making multi-story units available and that customers could now have a Cover as their primary residence, rather than an ADU. While designing those single-family homes isn’t any harder for Cover—its Lego blocks can be configured into any shape—it does add a bit more complexity to the permitting process.

“The code that you have to comply with, the engineering that you have to do, the drawings that you have to submit, the clearances that you have to get from different city departments, that’s the same for ADUs and single-family homes,” says Rivas, “but there’s some extra streamlining that applies to ADUs [in California].”

“They’re far more ignition-resistant than your typical 2×4 wood home.”

Alexis Rivas

Cover wasn’t planning to announce its single-family and multi-story units until March 2025, but it moved up the launch so that it could offer the options to homeowners affected by the L.A. wildfires. It also committed to waiving its custom design fees for people looking to rebuild after the fires, donating up to 2,000 hours of its architects’ and engineers’ time.

Rivas tells Freethink that the company has spoken with hundreds of people in Altadena and Pacific Palisades who lost their homes in the fires and has already submitted permits to build units for some of them.

In some cases, these homeowners are looking to Cover to build them an ADU that they can live in until their primary residence is built through traditional methods. In others, they’re looking to Cover to build their new single-family home or an ADU and their primary home.

“There’s a wide range,” Rivas told Freethink. “This morning I met with a couple from the Palisades whose temporary living situation is not great. They’re like, ‘We just want to get back into the Palisades as soon as possible. Let’s build an ADU that we’ll like and that will retain its value, and then we’ll build a home shortly after.’”

Those who opt for one of Cover’s units over a traditional stick-built home could be less likely to have to go through the rebuild process again if they’re unlucky enough to have a wildfire sweep through their neighborhood in the future.

“They’re steel, meaning they’re noncombustible,” says Rivas. “That doesn’t mean they’re entirely fireproof—nothing is entirely fireproof— but they don’t add fuel to the fire, and they’re far more ignition-resistant than your typical 2×4 wood home.”

“That’s where it starts,” he continues. “We’ve also got double-paned tempered windows, which means that they have a higher temperature that they would break at. The window frames are aluminum instead of vinyl—again, they melt like everything else, just at a higher temperature.”

The lack of attics in Cover’s units helps increase their fire resilience, too.

“Attics are actually how most homes catch fire,” Rivas tells Freethink. “Embers get in through the vents that go into the attic, which is exposed wood and insulation. Immediately, the attic ignites, and then the rest of the home catches fire soon after.”

“If the city is becoming a constraint to building, that’s not a good thing.”

Alexis Rivas

Cover’s goal is to help people get into their new homes as quickly as possible, and it seemed like the city of Los Angeles was on the same page: On January 14, Mayor Karen Bass issued an executive order designed to streamline the fire rebuild process.

“This unprecedented natural disaster warrants an unprecedented response that will expedite the rebuilding of homes, businesses, and communities,” she told reporters. “This order is the first step in clearing away red tape and bureaucracy to organize around urgency, common sense, and compassion. We will do everything we can to get Angelenos back home.”

Cover submitted its first fire rebuild permit application to the city on February 4, and unfortunately, it’s actually taking longer to get approvals for this build—a flat lot with building plans identical to ones previously approved by the city—than some of its previous ADUs.

“If you’re trying to get as many people back into their homes safely and quickly, what you want to be doing is as soon as a lot gets cleared by the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers, builders should be swooping in the next day and starting work,” Rivas tells Freethink.

“If the city is becoming a constraint to building, that’s not a good thing,” he adds. “The goal for the city should be that every single lot has a permit to build a month before their lot is cleared, ideally, so that people can get bids and organize themselves. That’s what the aim should be. It’s frustrating. I just don’t see that.”

Rivas does see a path to getting there, though.

“I think there are a lot of specific actionable things,” he tells Freethink. “One is working with companies that do prefabricated homes to say, ‘Here’s a list of pre-approved homes. If you’re on a flat lot in these areas that are straightforward, you can just go ahead and build these pre-approved plans.’”

Even if it wasn’t willing to do away with permits for those homes entirely, the city could switch to making permits for them available over-the-counter the day an application is submitted.

Giving government workers more agency to make decisions without waiting for instructions from their superiors could speed up the permitting process, too, as could allowing for self-certification, where the architects and engineers on a construction project certify that it meets building codes themselves and assume any risk if it doesn’t.

“Self-certification should be reserved for straightforward projects,” says Rivas. “If you’re building a multi-story tower, you shouldn’t go through this process, but if you’re building a single-family home under 4,000 square feet on a flat lot with simple foundations, you should be able to self-certify it.”

“This is actually not uncommon,” he adds. “New York City does it for certain projects. Chicago does it. San Diego does it. A lot of cities already do self-certification as a way of speeding up permits.”

“Hoping we can clear this up and get this permit to the finish line!”

Alexis Rivas

Implementing these changes wouldn’t just help people who’ve lost their homes to L.A.’s wildfires. Permitting delays are a problem experienced by builders of all kinds of homes all across the U.S., so taking action to prevent them could help alleviate the housing crisis nationwide.

Cover may have only just opened its new factory, but Rivas is already looking ahead to the next one, which will be even larger and more heavily automated, allowing the company to build thousands of homes every year for people in places beyond Southern California.

For now, though, the focus is on helping Angelenos recover.

Rivas has been providing daily updates on the permitting process for the first fire rebuild on X, and on March 5—29 days after the company submitted its permit application—he shared that a member of the L.A. city council had reached out to talk about the delays.

“Hoping we can clear this up and get this permit to the finish line!” he tweeted. “It’s the first of many.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].