This article is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Saturday morning by subscribing above.

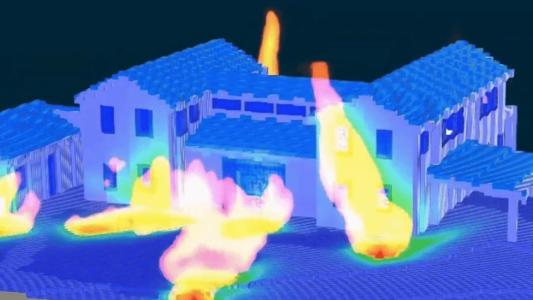

It’s 2040. You’re at your doctor’s office, going over the results of your genome analysis. An advanced AI has identified patterns in your DNA code that suggest you’re at high risk of developing a certain disease in the future. Thankfully, the same AI can be used to design a treatment.

Generative biology

Biology—the study of living things—has been going on since prehistoric times when our ancestors first determined through trial and error which plants were food and which were poison.

Over the next tens of millennia, scientists would develop increasingly advanced new tools to help them in their quest to understand the living world, eventually leading to the breakthrough discovery that everything we could want to know about an organism is written in its DNA.

Now, an artificial intelligence (AI) called Evo 2 is entering the biology lab, and the introduction of this tool could signal the start of a new era in biology, one in which scientists aren’t just trying to decipher the code of life, but rewriting it from the ground up.

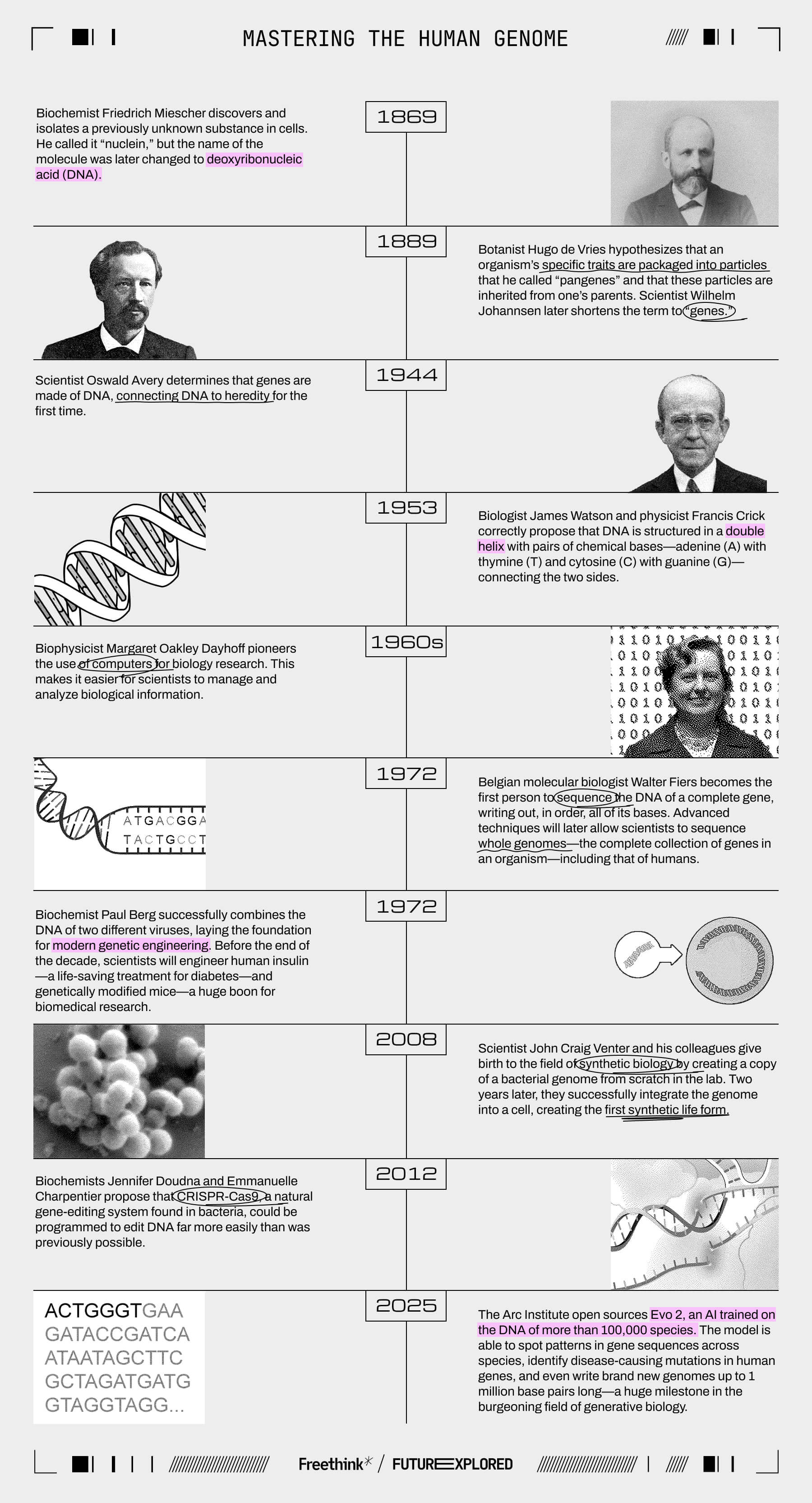

Where we’ve been

Where we’re going (maybe)

The genome is like an organism’s instruction manual, dictating the appearance and function of every cell in its body. While all humans have basically the same genome, about 0.1% of yours will differ from the reference human genome—there will be spots where you have a G instead of the standard A, for example.

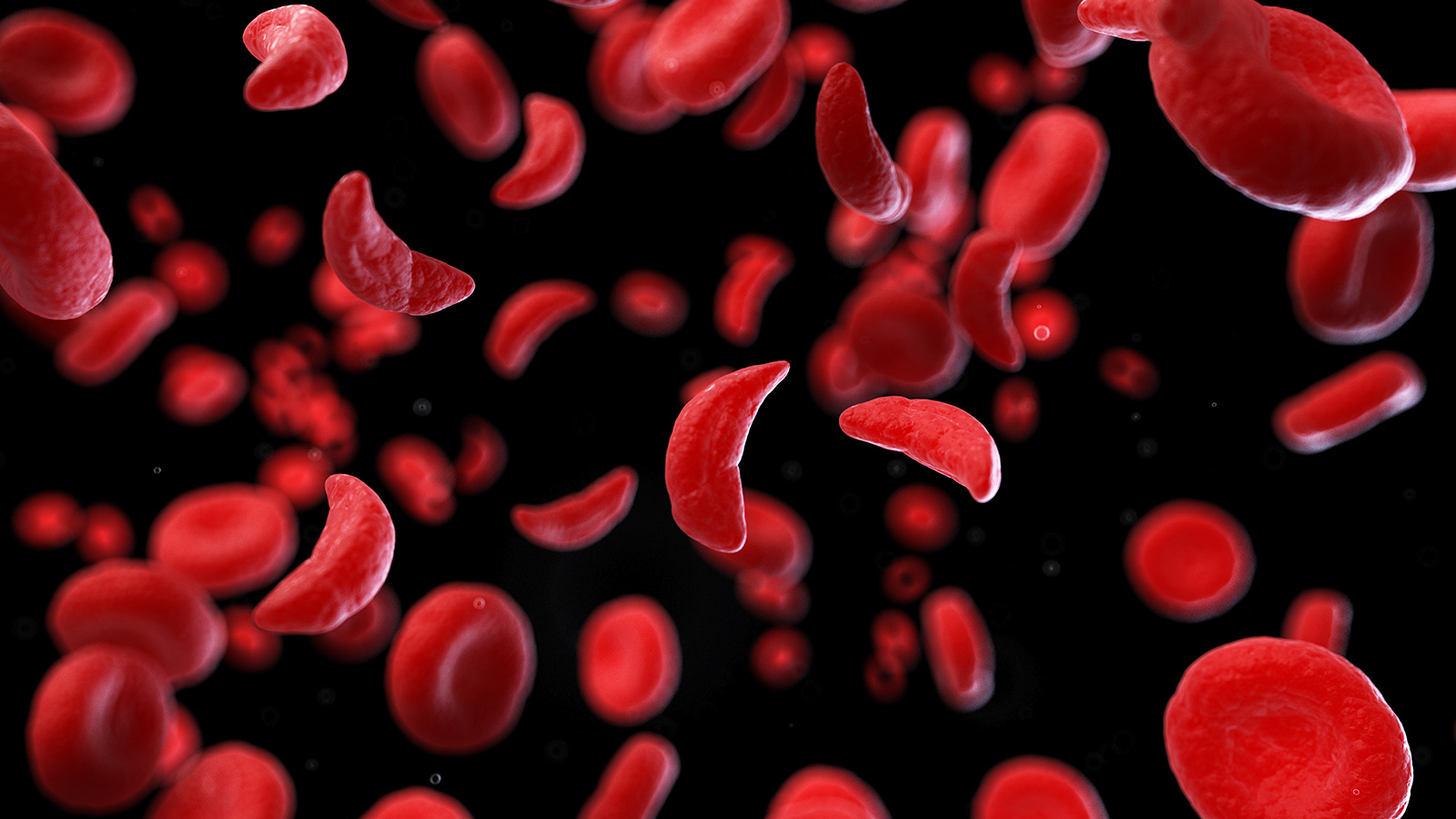

We call these differences “genetic variants,” and they play a key role in making you you, helping determine everything from your eye color to your blood type. They’ve also been linked to an estimated 7,000 diseases—the blood disorder sickle cell anemia, for example, is caused by variants in just one gene.

While we’ve determined that some genetic variants are benign and some put us at higher risk of certain diseases, others are “variants of unknown significance” (VUS), which Patrick Hsu, head of the Arc Institute, a nonprofit biomedical research organization, tells Freethink “is a kind of fancy word for we don’t know what the hell is going on.”

Figuring out what, if anything, these variants do could have a huge impact on healthcare because if they are implicated in a disease, that gives us a target to treat. We might be able to deliver healthy copies of the affected gene into cells or use gene-editing tools like CRISPR to correct the mutation.

Solving the mystery can be hugely challenging, though.

For one, only about 2% of the human genome contains DNA sequences that are “coding,” meaning they teach cells how to make proteins (the molecules that actually do the work in cells). The other 98% consists of “noncoding” DNA sequences that have no known biological function.

Researchers are starting to piece together the impact of some of this “junk DNA,” but the bottom line is the majority of VUS are in parts of the genome that might do something, but we don’t know what, making it hard to even begin to guess how they might affect our health.

Another issue is that genetic variants often don’t act alone. In 2022, for example, a study of 5.4 million human genomes identified 12,000 variants that influence height.

Heart disease, diabetes, and many other health problems are considered “polygenic”—caused by the combined effects of multiple genes—so a researcher hoping to identify the variant(s) responsible for a disease might need to be able to spot a pattern involving thousands of them in the genomes of multiple people with that disease.

That’s a lot to ask of a human, but it’s the sort of task an AI could excel at.

The technology

OpenAI’s 2022 release of ChatGPT may have propelled generative AI into the mainstream, but the field really got its big break in 2017, when researchers at Google introduced the “transformer,” a new kind of neural network architecture for language processing.

Instead of analyzing a text one word after another, transformers break the whole text into small “tokens” (individual words or even punctuation marks), look at them all at once, and then determine which are the most important based on their relationships to one another.

Armed with this information, a transformer-based AI can generate a response to a prompt by predicting what word is most likely to come first in an appropriate answer. It then predicts the next word and the next in the same way until it generates a complete response.

“We thought, ‘What would happen if we did that for DNA?'”

Patrick Hsu

Google introduced transformers as a tool for language translation, but researchers soon realized the architecture could be used to create AIs capable of generating human-like text, images, music, videos, and more in response to prompts. The kind of token changes—from words to pixels or music notes, for example—but the basic operation remains the same.

“People have been using these transformer-type architectures and these models that are trained on next-token prediction to decode many other domains, whether that’s language or vision or robotics,” Hsu tells Freethink. “We thought, ‘What would happen if we did that for DNA?'”

“The effects of natural selection are transmitted throughout generations of life via DNA mutations,” he adds, “so, in principle, by reading across massive data sets of DNA mutations, you might be able to connect these mutations to function.”

To test this theory, the Arc Institute teamed up with researchers at Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley, to create an AI model that could interpret and generate DNA sequences the same way others do text or images.

“We think of this as enabling an app store for biology.”

Patrick Hsu

From existing research, they knew a standard transformer architecture wasn’t going to work—the computational cost of analyzing long sequences of DNA was too high, and the architecture underperformed at the single-token resolution needed to make sense of genetic variants.

“We had to develop a new frontier deep learning architecture beyond the vanilla transformer that is basically standard in the field,” says Hsu.

They named their new architecture “Striped Hyena” (a nod to the “hyena layers” incorporated alongside the transformer layers) and used it as the basis for Evo, an AI model trained on the genome sequences of more than 2.7 single-cell organisms and microbes.

And it worked. After training, Evo was able to make accurate predictions about the relationship between an organism’s genome and its function. It could predict which genes were essential in a bacteria, for example, and how a genetic variant would impact a gene’s protein performance.

It could also generate DNA sequences more than 1 million base pairs long. As a proof of concept, the researchers prompted Evo to write the code for a new CRISPR-Cas system, and after synthesizing the system in the lab, the team found it to be fully functional.

The next Evo-lution

The Arc team unveiled Evo in February 2024, making both the model and a large training dataset available to the public for free, and one short year later, it’s back with the next iteration of the technology: Evo 2.

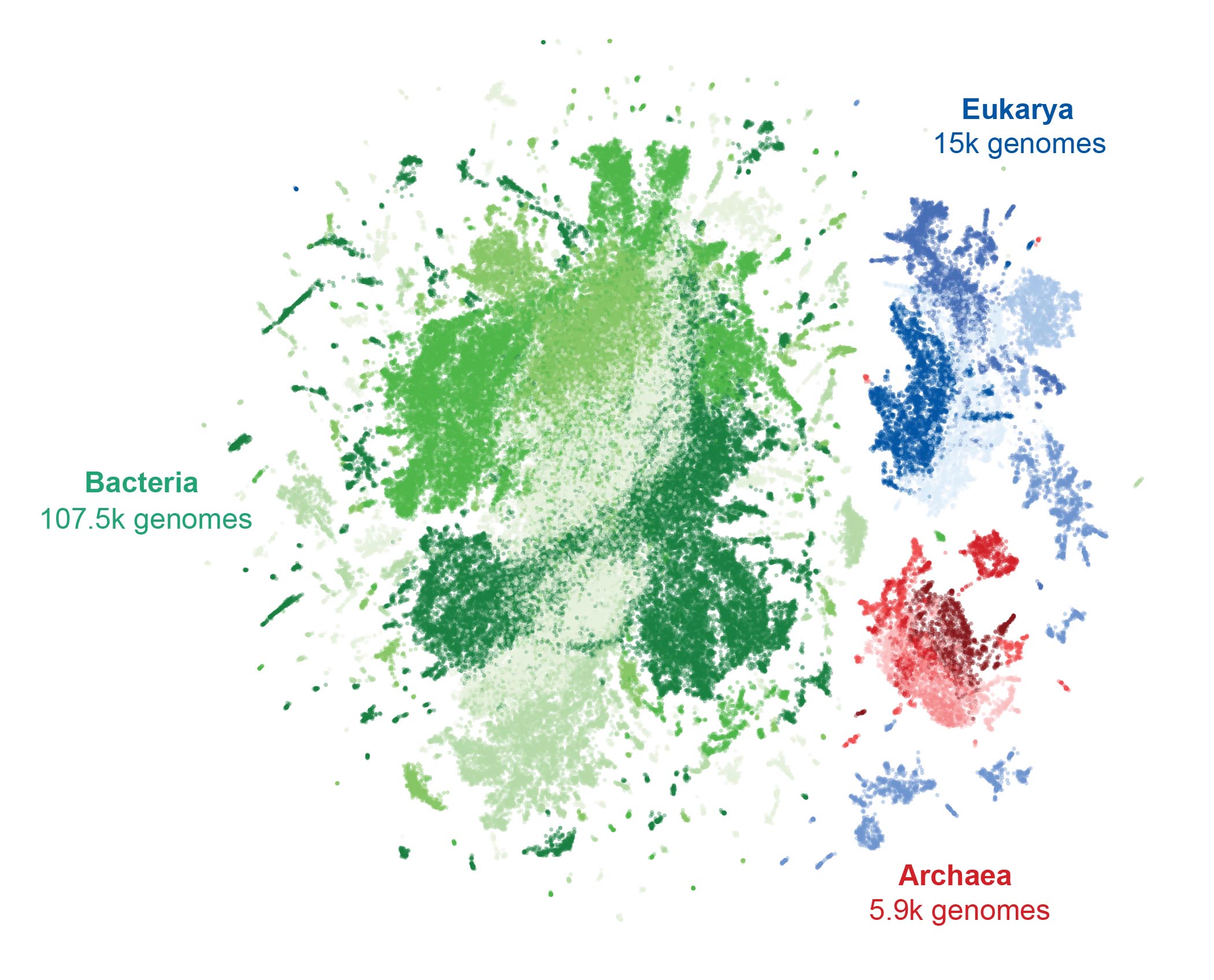

This model—created in collaboration with researchers at Stanford University, University of California, Berkeley, University of California, San Francisco, and Nvidia—is trained on a massive dataset of more than 9.3 trillion DNA letters from the genomes of nearly 130,000 species across the tree of life, including humans.

Thanks to an updated architecture, Striped Hyena 2, Evo 2 is able to analyze up to 1 million DNA bases at a time—a significant increase over Evo 1’s 131,000 limit—and generate sequences as long as the genomes of some bacteria.

To demonstrate the potential of Evo 2’s prediction power, the Arc team focused on the BRCA1 gene. A small number of variants in this gene are known to dramatically increase a person’s risk of breast cancer, but genetic testing often turns up many VUS, meaning there’s potentially still a lot we could learn about the gene’s role in the disease.

“The question for folks who have these VUS mutations is, ‘Do I do anything other than getting an annual mammogram?’” says Hsu.

When they tasked Evo 2 with predicting whether a variant in BRCA1 was benign or potentially pathogenic—could cause disease—90% of its answers matched those in a dataset of predictions based on the results of lab experiments. Evo 2 also proved to be better than any other AI model at classifying variants in those tricky noncoding segments of the gene’s DNA.

“Evo 2 is the only model that is able to score or predict the effects of both coding and noncoding mutations,” Hsu explained during a press briefing on February 19. “It’s the second-best model for coding mutations, but it’s state-of-the-art for noncoding mutations, which this model, AlphaMissense from DeepMind, cannot score.”

Evo 2 achieved this without being trained on anything specifically related to BRCA1, too. If someone were to take the model and finetune it on data related to that particular gene, they could potentially improve its performance.

“We think of [Evo 2] as the foundational layer of biological information, and people can build different applications,” says Hsu, adding, “We think of this as enabling an app store for biology.”

“On the design side, this is starting to touch things that feel much more science fiction.”

Patrick Hsu

To demonstrate Evo 2’s ability to generate DNA sequences, meanwhile, the Arc team tasked it with writing three kinds of increasingly complex genomes: a mitochondrial genome, a bacterial genome, and a yeast chromosome.

The AI was able to generate sequences that encoded all of the genes you’d expect to see in a real mitochondrial genome, which is about 16,000 base pairs long. Its outputs for the others weren’t as realistic, but they contained many of the genes you’d expect to see in nature.

“On the design side, this is starting to touch things that feel much more science fiction,” Hsu tells Freethink.

Looking ahead

Just like it did with Evo 1, the Arc team has open-sourced Evo 2, making its code available on GitHub, as well as integrating it into Nvidia’s BioNeMo framework. Researchers can also opt to interact with it using the user-friendly Evo Designer interface.

Sudarshan Pinglay, head of the Pinglay Lab at the Seattle Hub for Synthetic Biology, is one of the researchers taking advantage of Evo 2. His team is already making some of its designs in the lab just to see what they look like, and he envisions a future in which he can use an Evo model to generate genomes unlike any that exist in nature.

“I think models like Evo will really help us design truly synthetic genomes that basically look nothing like life that was evolved,” he tells Freethink, adding, “I don’t think Evo is the finish line. I think it’s a starting point for models for whole genome design that basically break the shackles of evolution.”

The fact that genomes generated by Evo 2 were a significant improvement over Evo 1’s DNA sequences suggests that that’s where the technology could be heading.

“It’s definitely following the scaling laws,” says Hsu, “which is another machine learning term that underpins that more compute, more parameters, and more data are all really predictable ways to improve the performance of these machine learning models.”

He looks forward to the point that an Evo model could be used to look at all the variants across a person’s entire genome and generate risk scores for diseases associated with multiple genes.

“We showed a million token context, but the human genome is 3.2 billion bases long, so it would be nice if we had a three billion token context model,” says Hsu. “I don’t know if that’s Evo 3, but we want that Evo.”

We’d love to hear from you! If you have a comment about this article or if you have a tip for a future Freethink story, please email us at [email protected].